Vitruvian Man

What is the Vitruvian Man?

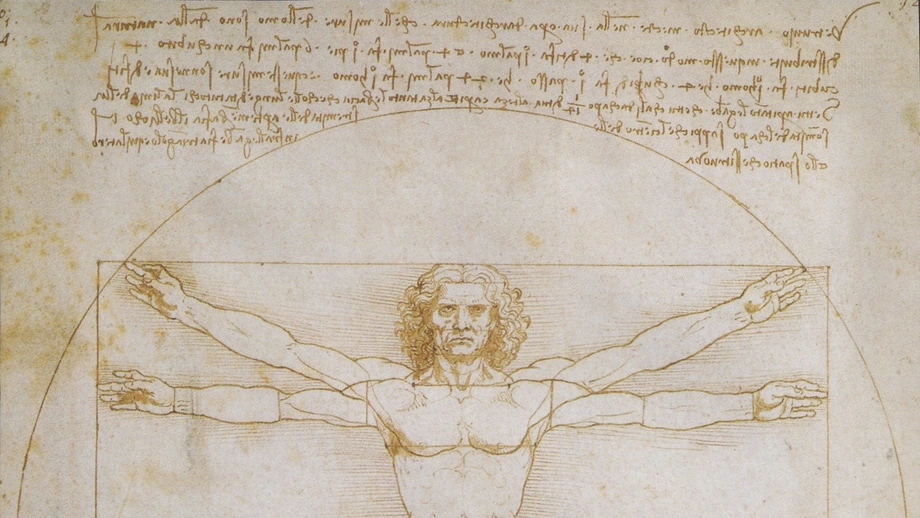

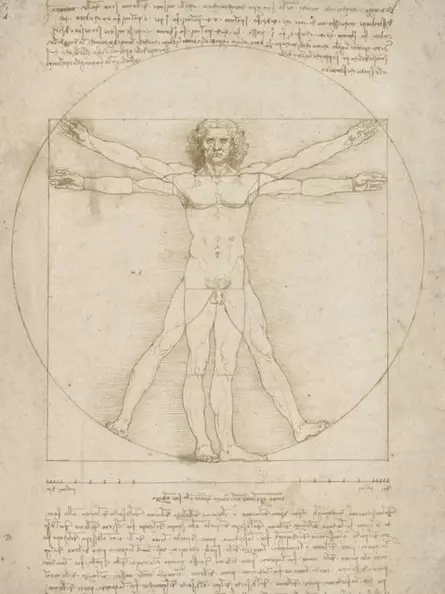

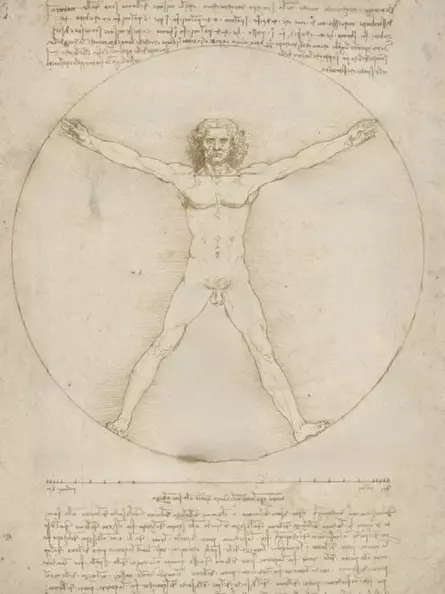

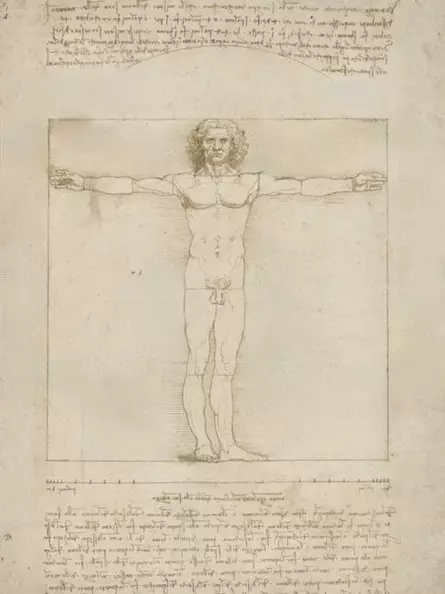

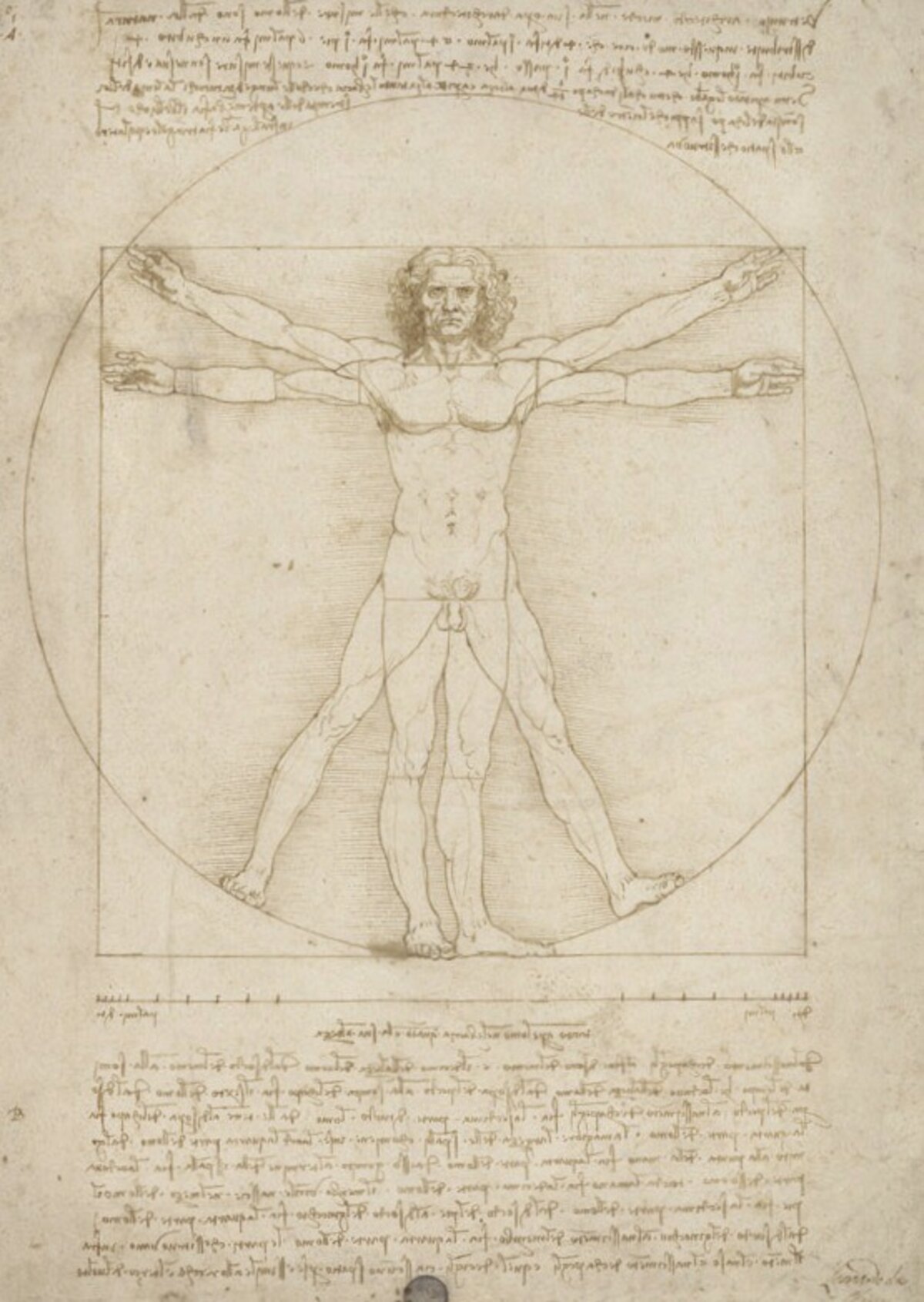

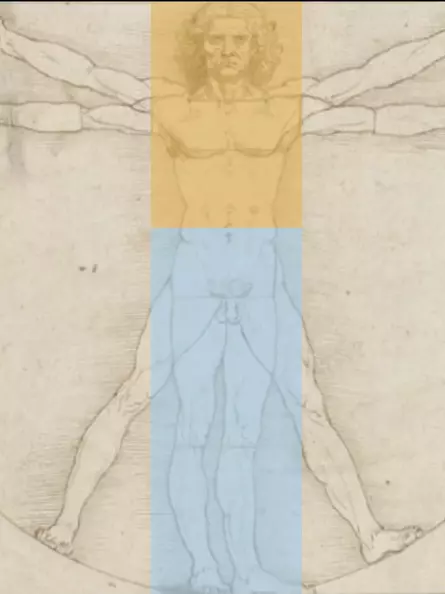

The Vitruvian Man is a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci. It shows two superimposed views of a man, each enclosed in a circle and a square respectively. The drawing is now in the Galleria dell' Accademia museum in Venice and is rarely exhibited in public for conservation reasons.

Two views of a human being superimposed

The study sheet refers to a description of the ideal proportions of man in the work "Ten Books on Architecture" by the ancient architect Vitruvius (1st century BC). The "Ten Books on Architecture" are the only surviving book on architecture from antiquity. Since the work has survived without illustrations, it was unclear for a long time how Vitruvius imagined the ideal proportions of a human being. Leonardo was the first to succeed in illustrating Vitruvius' description in such a way that all the rules mentioned by Vitruvius are reflected in the drawing.

What is the significance of the Vitruvian Man?

The Vitruvian Man has mainly an architectural-theoretical meaning. The drawing illustrates the ancient insight that the dimensions of the individual limbs of a human being follow mathematical laws. Therefore, buildings erected by humans should also be as well-proportioned and well thought-out as humans themselves. Because Leonardo's sketch combines a circle and a square in one representation, the drawing is also brought into a spiritual context. The circle is then a symbol of femininity, the square a symbol of masculinity. Moreover, Leonardo is said to have hidden in the drawing a solution to an old mathematical problem, the squaring of the circle.

Overall, the Vitruvian Man demonstrates the ancient view that all human beings are composed of the same proportions, and differ from each other only in their variation therein. For example, some people have slightly longer arms or slightly shorter legs, but on average all people show the proportions established by Vitruvius. Therefore, until the introduction of the metre, the earlier units of measurement corresponded to the standardised lengths of certain parts of the body. For example, there was the unit of measurement 1 cubit (from the elbow to the tip of the finger) or also 1 foot (foot length), which is still used today in English-speaking countries.

For no temple can be justified without symmetry and proportion in its construction if it does not, like a well-formed human being, bear within itself a precisely executed law of arrangement.

Leonardo da Vinci's paintings cannot be understood without examining the geometry of the picture

Vitruvian Man

Leonardo da Vinci

around 1490

Pen and ink on paper

34,4 × 24,5 cm

Galleria dell' Accademia, Venice

Description

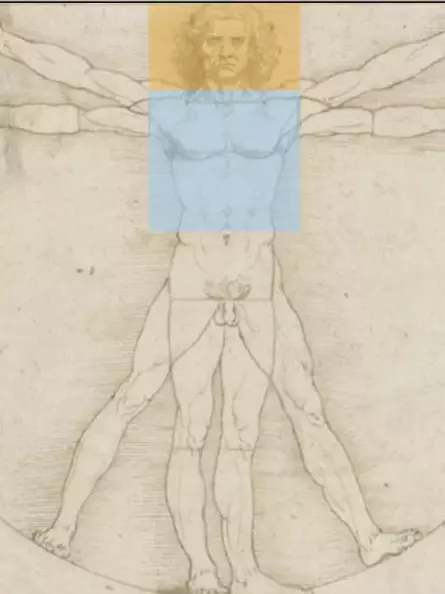

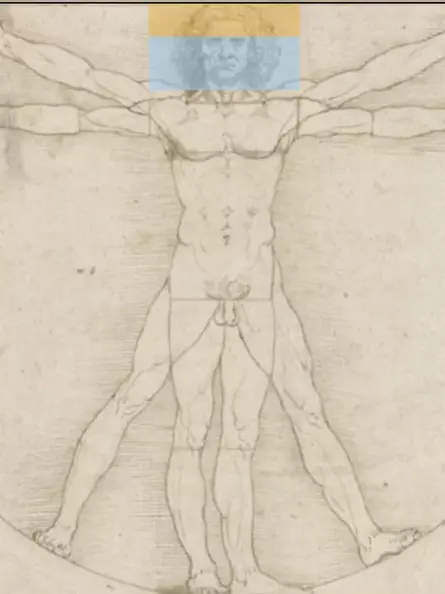

A sheet of paper. A drawing in the middle of the sheet. An older naked man with curly hair is shown in frontal view. Arms and legs are shown in two views each. They are arranged in such a way that the arms stretched out sideways and the man's body height span a square.

A second view superimposes the first. It shows the raised arms and the spread legs of the man. The navel forms the centre of a circle that completely encloses the man. The man, the circle and the square have three points in common on the middle finger of the raised hands and on the right toe. On the man himself there are further lines dividing his body into sections.

A horizontal line is shown below the drawing. It is as wide as the square spanned by the man and divided symmetrically by transverse strokes.

Above and below the drawing are handwritten notes in Italian. The texts are written in mirror writing. In the upper part, the author has led the writing around the circle. In the lower right corner the drawing is signed "Lionardo da Vinci".

The sheet is in good overall condition, but has stains and discolourations here and there.

Leonardo's inscription - the original text

For a better overview, Leonardo's text is divided into paragraphs here.

Above the drawing

"Vitruvius, the architect, in his work on architecture, says that the measurements of the human body are distributed by nature as follows:

4 fingers make a palm,

4 palms make a foot,

6 palms make a cubit;

4 cubits make the height of a man. And

4 cubits make a step, and

24 palms make a man;

and these measurements he used in his buildings.

If you open your legs so wide that they reduce your height by 1/14, and spread and raise your arms until your middle fingers touch the height of your head, you must know that the center of the spread limbs is at the navel, and the space between the legs is an equilateral triangle."

Below the drawing

"The length of a man's outstretched arms is equal to his height.

From the hairline to the underside of the chin is one-tenth of a man's height;

from the bottom of the chin to the top of the head is one-eighth of a man's height;

from the top of the chest to the top of the head is one-sixth of a man's height.

From the crown of the chest to the roots of the hair is the seventh part of the whole man.

From the nipples to the crown of the head is the fourth part of a man.

The greatest width of the shoulders contains within itself the fourth part of a man.

From the elbow to the tip of the hand is the fifth part of a man,

and from the elbow to the armpit is the eighth part of man.

The whole hand is the tenth part of man;

the beginning of the genitals marks the middle of the man.

The foot is the seventh part of man.

From the sole of the foot to below the knee is the fourth part of man.

From below the knee to the beginning of the genitals is the fourth part of the man.

The distance from the bottom of the chin to the nose and from the hairline to the eyebrows are each the same, and like the ear, one-third of the face."

Deviations from Vitruvius' text

Leonardo's accompanying text to the drawing is a summary of the first chapter of the third book of "Ten Books on Architecture" written by the ancient architect Vitruvius. The full text of the chapter can be found at the bottom of this page.

The units of measurement quoted by Leonardo at the beginning for finger, palm, cubit etc. correspond to the units of measurement in ancient Greece that Vitruvius also used. All measurements were based on the finger width (1 dactylos), the smallest unit of measurement. In ancient Greece, multiples of 2 and 3 were used for simplicity. Thus they fixed the width of a man with outstretched arms at 96 finger widths (1 orguia).

The number 96 results from 3 * 2 * 2 * 2 * 2.

Vitruvius writes that the centre of the body is in the navel, without explaining this in detail. It is Leonardo's merit to define the position of the navel in such a way that the human being as a whole appears natural: "If you open your legs so wide that they reduce your height by 1/14 ...".

Below the drawing, Leonardo reproduces the content of Vitruvius' remarks correctly for the most part, but deviates from Vitruvius' statements in some details.

- For example, Vitruvius states 1/6 of the body height for the length of the feet, Leonardo, however, shortens it to a more aesthetic 1/7 I

- Leonardo adds to the statement according to which the length from the crown of the chest to the roots of the hair should also be 1/7 I

- There is also a contradiction with the drawing. Leonardo writes: "From the elbow to the tip of the hand is the fifth part of the human being", but the length drawn is 1/4 II

In this respect, Leonardo's drawing is not a mere illustration of Vitruvius' specifications, but a critical reception that does not shy away from incorporating its own findings from anatomical and mathematical studies, although it does not remain free of errors.

The ancient architect Vitruvius

The idea for this study of proportions did not come from Leonardo himself, but from the ancient architect and engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, known as Vitruvius.

Who was Vitruvius?

Vitruvius (c. 80-70 BC to c. 15 AD) was an important architect and war engineer during his lifetime, working first for the Roman ruler Julius Caesar, and then for his successor Emperor Augustus. In contemporary sources, Vitruvius is only mentioned in passing, and so all that is known about his life is what he wrote down in his only surviving work, "De architectura libri decem" (Latin for 'Ten Books on Architecture').

Ten books on architecture

The title of the work is slightly misleading, rather it is a book of about 400 pages with 10 chapters. The book is now considered the only surviving book on architecture and civil engineering from the time of Greco-Roman antiquity. Vitruvius claims that it is the only summary of the art of building at that time up to that time, which is also confirmed by modern research.

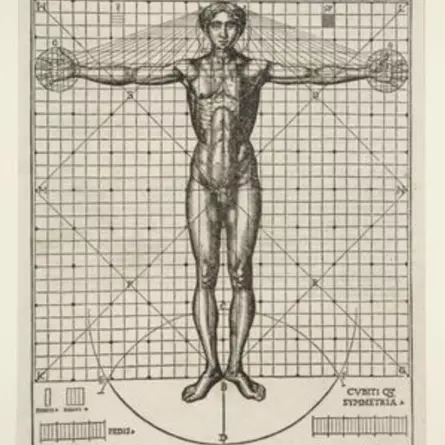

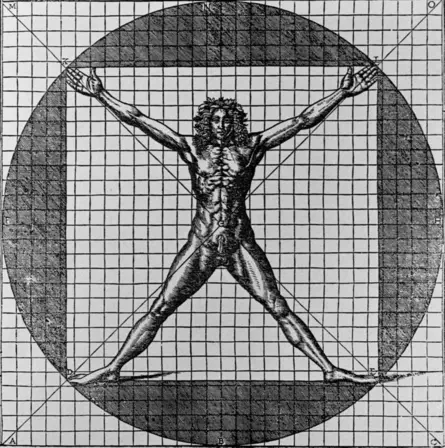

In the third chapter, that of temple construction, Vitruvius introduces the doctrine of the well-formed body (lat 'homo bene figuratus'). He showed that human proportions follow universal rules that should be applied to all human works, e.g. architecture. Leonardo refers to this passage with the drawing of the Vitruvian Man. The surviving editions of Vitruvius' work are not illustrated, which has led to various visual interpretations of Vitruvius' indications. Above all, it was unclear where the centre of the circle encompassing the human being should be.

Contrary to what the title suggests, the book is not only about architecture. Vitruvius, like other ancient master builders, had a more universal understanding of architecture. Thus, he does write at the beginning about typical topics such as architectural history, urban planning, types of buildings and material science. But the last four chapters deal with initially unexpected topics, such as the production of paints, wall painting, water supply, astronomy, timekeeping, mechanical engineering and implements of war.

Rediscovery during the Renaissance

Vitruvius' book has survived in numerous copies and was increasingly read and received during the Renaissance. The first book was printed in the 15th century and Leonardo also owned a copy. He was not the only one to illustrate Vitruvius' information on human proportions. Numerous authors made sketches on the subject, but Leonardo's drawing is considered the first to fulfil all of Vitruvius' specifications and also the most beautiful on the subject.

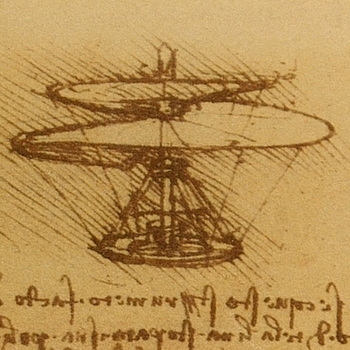

The Vitruvian Man is only one part of Leonardo's exploration of the book. Among other things, Leonardo constructed a device for measuring long distances, the hodometer, based on a description by Vitruvius. This enabled Leonardo to create the first modern city plan (city plan of Imola, 1502).

Vitruvius' book remained one of the most influential textbooks in architecture until the early 20th century. Only with the development of modern building methods, such as reinforced concrete construction and architectural designs that were no longer based on classical geometry, did Vitruvius' work lose importance.

The author has not drawn in the circumference that the arms and feet should touch

The figure appears strongly distorted because the author has placed the centre of the circumcircle and the surrounding square in the same point. In addition, the hands, feet and head appear disproportionate

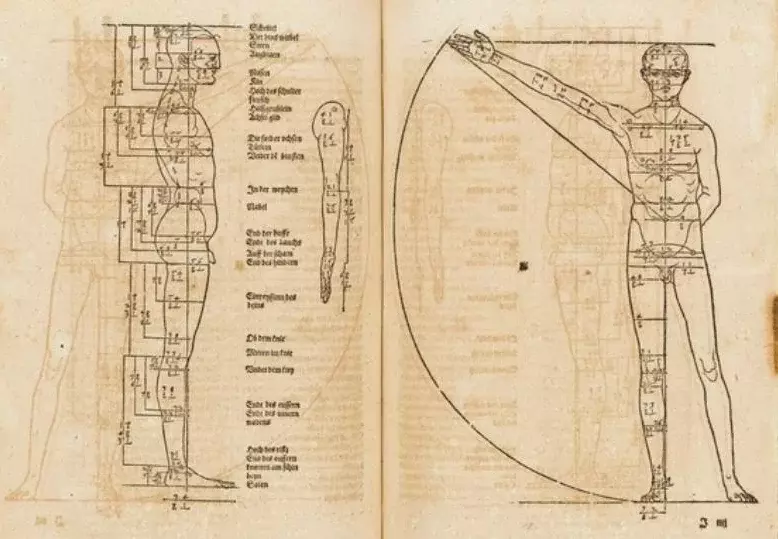

Dürer travelled to Italy several times and became acquainted with the works of Leonardo, among others. Numerous references to Leonardo can be traced in Dürer's work

Time of origin

Nothing is known about the time of the sheet's creation, nor are there any contemporary sources that prove its existence. Nevertheless, Leonardo's authorship is undisputed among experts. Since Leonardo's writing changed in the course of his life, the date of the sheet's creation can be determined to be around 1490 by comparison with dated notes by Leonardo, although this cannot be determined with absolute certainty. The focus is on a book by the mathematician Luca Pacioli. Leonardo's Vitruvian Man could have been created as an illustration for this book.

Luca Pacioli's Vitruvian Studies

Like Leonardo, the mathematician Luca Pacioli (1445-1517) was concerned with human proportions and the teachings of Vitruvius. Luca Pacioli was a student of the exceptional painter Piero della Francesca, and later an important mathematician. He wrote numerous treatises on geometry. Still significant today is Pacioli's book on double-entry bookkeeping, which is the first complete summary of this method. He also wrote a summary of the algebra known at the time.

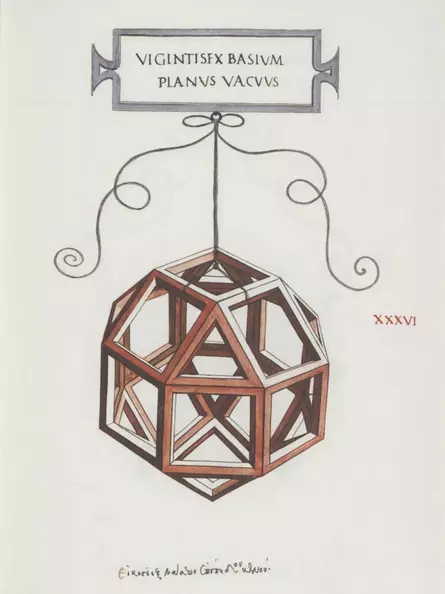

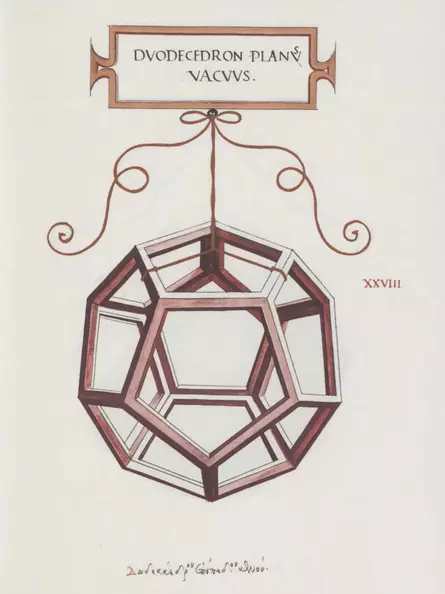

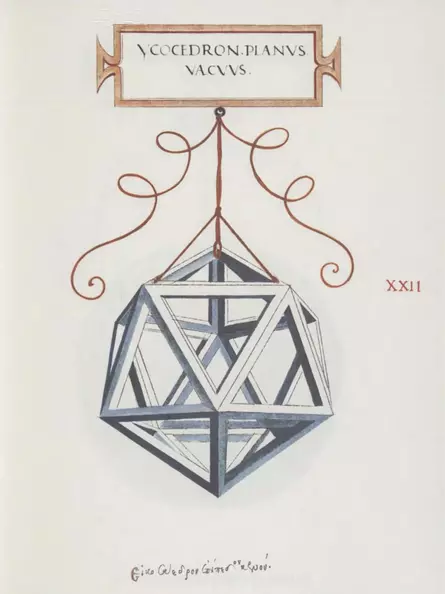

Leonardo was about 43 years old at the time of the painting's creation, Pacioli seven years older. The glass geometric figure on the upper left is a cuboctahedron, on the lower right a dodecahedron is depicted.

Leonardo's collaboration with Pacioli

Around 1498, Luca Pacioli was invited by the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza. Leonardo was staying at the duke's court at the same time and this is how he met Luca Pacioli. They began a collaboration that lasted several years and extended beyond the two years they spent together in Milan. Among other things, Leonardo made 60 drawings of geometric solids for Pacioli's planned book "Divina Proportione" ('Divine Proportion').

Leonardo's illustration for Pacioli's book "Divina Proportione

The skeletal representation of the figures was novel and is a Leonardo invention

The figures are drawn very vividly and in correct perspective

Pacioli's book "Divina Proportione"

Pacioli completed his book, which was later to be very influential, around 1498. Initially, only three manuscripts were handmade to serve as particularly beautiful specimen copies for noble backers; one went to the Duke of Milan.

In the book, Pacioli deals with the laws of geometric solids, the golden section and its applications in architecture. In addition, he largely adopts essays by his teacher Piero della Francesca and explains numerous passages from Vitruvius' main work "Ten Books on Architecture". Among others, the passage that is also quoted by Leonardo on the sheet with the Vitruvian Man. Since Pacioli's book contains some illustrations of the proportions of the face, possibly made by Leonardo, it stands to reason that Leonardo's Vitruvian Man was to become part of Luca Pacioli's book "Divina Proportione" in a revised form (i.e. without handwritten explanations). However, this cannot be substantiated. Leonardo's drawing would certainly have complemented Pacioli's explanations of Vitruvius' theory of proportion well.

It is remarkable in this context that Pacioli simply takes over Vitruvius' details for his book. After all, Leonardo had previously made deliberate changes to it when, for example, he shortened the foot length from 1/6 to a more aesthetic 1/7 of the body height. The collaboration between Pacioli and Leonardo was very close, possibly they were friends. When the Duke of Milan was overthrown by the French, they left the city together. It is therefore incomprehensible that Pacioli did not incorporate Leonardo's improvements of the Vitruvian Man into his book.

Plato's idea of the microcosm and macrocosm

Leonardo's study sheet is not to be considered on its own, but rather the sheet is part of a broad examination by Renaissance scholars of the ideas of the ancient masterminds, especially those of the scholar Plato.

Plato, Vitruvius, Pacioli and also Leonardo believed that all natural forms could be traced back to simple geometric proportions. No matter whether it was the size of the planets or the length of their orbits (macrocosm). Or whether it was about the manifold forms of plant blossoms, insect bodies down to the smallest parts, the atoms (microcosm). And according to ancient teachings, all these proportions were designed in the greatest possible harmony. Integer proportions such as halves, quarters and eighths were just as much a part of the explanation of the laws of nature as irrational number ratios such as the circle number Pi, the golden section or the square root of 2 (known today as Din A4 format).

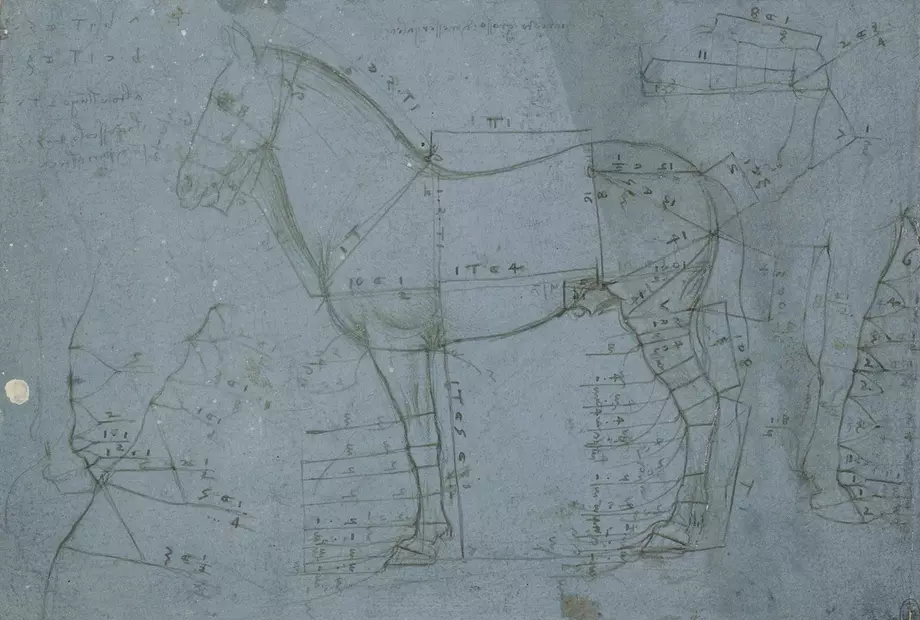

Application of Vitruvius' rules in architecture

Humans, as part of nature, were also designed in harmonic proportions according to the conception of the time. Even if people look different due to slight deviations, they are on average of the same shape. Just as a horse can be clearly recognised by its proportions, the appearance of a cat or a sparrow is determined by the proportions of the limbs of their bodies.

Since everything in nature was subject to the proportions of its parts, everything created by man should also be determined by the proportions of its parts. This principle is still influential in architecture today, even though there are increasing trends that try to soften this principle, which has been valid since antiquity, e.g. the chaotically structured buildings of Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928-2000) or the flowing forms of the architect Zaha Hadid (1950-2016).

Churches (temples) in particular were the architectural highlights of their city for many centuries. Their beauty derives from the proportions of their limbs, which follow clear geometric structures, which is particularly evident in the geometric rose above the main entrance

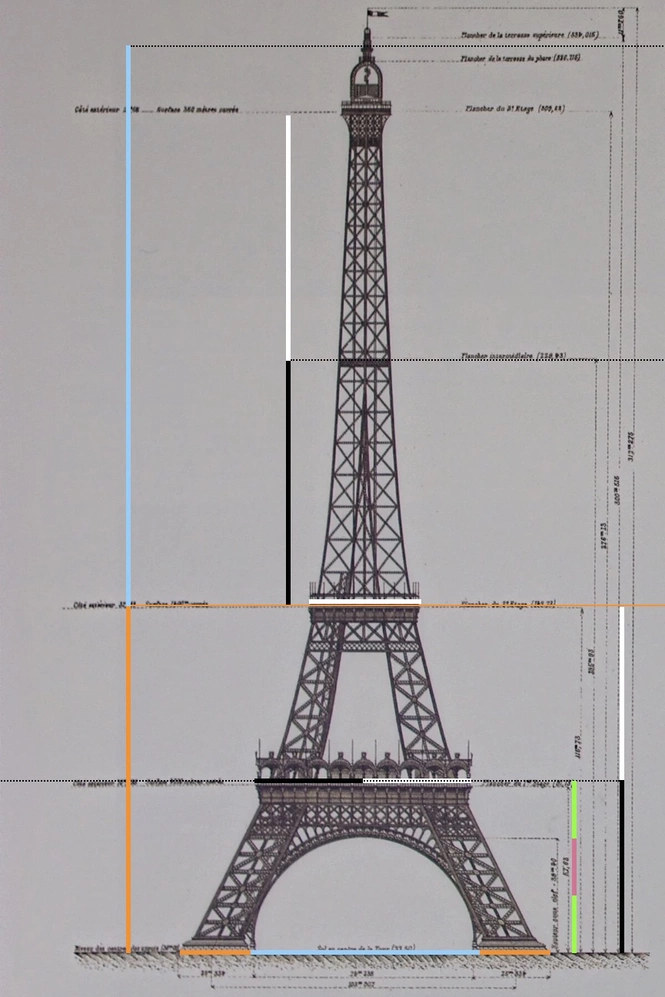

The Eiffel Tower shows clearly recognisable proportions of its parts. Golden section (blue/orange), halves (black/white) and thirds (red/green). The millennia-old principle of proportional order can also be seen in castles, skyscrapers and other architectural designs

More Proportion Studies

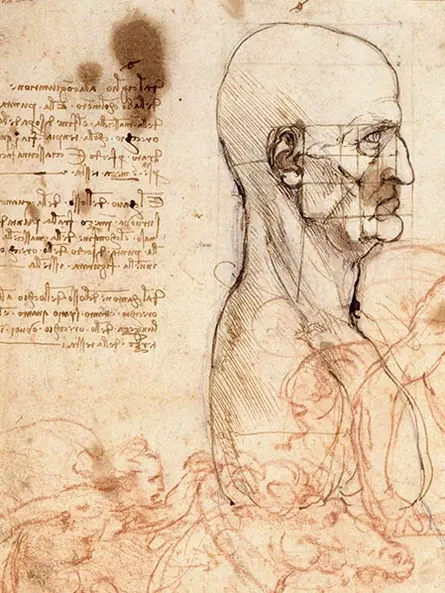

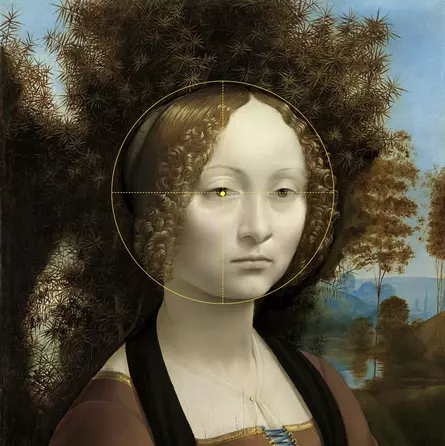

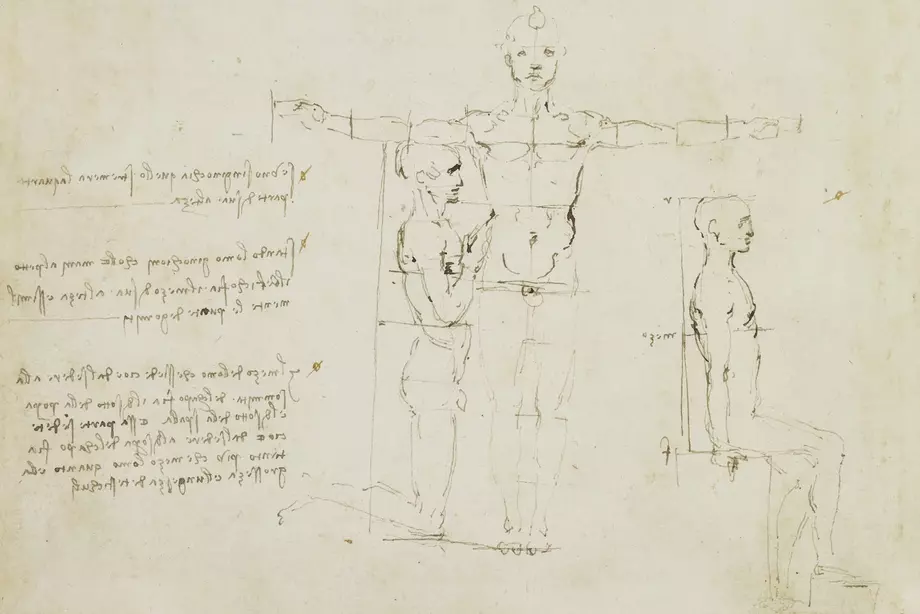

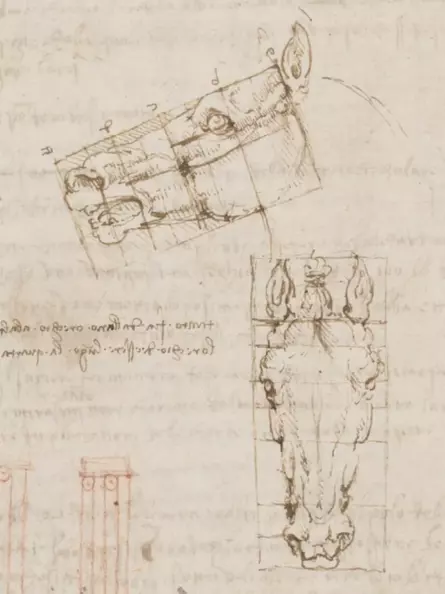

The Vitruvian Man is not Leonardo da Vinci's only study of proportions. As his notebooks show, he often dealt with the subject.

Leonardo notes that the head in profile can be drawn into a circle, and that the centre of this circle lies in the ear

Ginevra's head, turned slightly to one side, is inscribed in a circle whose centre is in her right eye. The portrait shows the great influence of Leonardo's studies of proportion on painting

Leonardo shows here that the height of a kneeling man is shortened by 1/4. Likewise for a seated person, since the distance from the foot to the knee (kneeling person) or from the knee to the hip (seated person) is a quarter of the body height

Leonardo's studies of proportions were not limited to people. He sought the "divine proportions" in all phenomena of nature, as here in horses.

Owner

In the possession of Francesco Melzi

It is believed that the Vitruvian Man became the property of his pupil Francesco Melzi (1491-1570) after Leonardo's death. Melzi accompanied Leonardo until his death and then became the designated executor of his will. He began to sort the numerous writings, called codices, thematically. One result of this work is Leonardo's "Book of Painting". After Melzi's death, the codices were scattered all over Europe. In the process, they suffered great damage. Some were cut up into individual pages, and in some cases even the individual leaves were cut up even further. Many sketch pages were also lost. Experts estimate the original volume of the codices at 20,000 pages, of which, however, only about 6,000 remain today.

In the possession of Giuseppe Bossi

What is known today about the whereabouts of the Vitruvian Man comes from the diary of the Italian artist Giuseppe Bossi (1777-1815). Bossi wrote in his diary that he had acquired the sheet in 1807, along with many other Leonardo drawings, from the de Pagave family. The de Pagave family in turn had received the drawings from Countess Anna Luisa Monti, heiress of Cardinal Cesare Monti (1594-1650). Beyond Bossi's statements, the origin of the sheet cannot be proven with sources.

Bossi's Significance for Art History

Bossi is not without controversy, as he is said to be responsible for various art forgeries. For example, numerous drawings that are today considered Leonardo or Raphael drawings are actually said to have come from him.

Bossi himself was a famous painter who carried out various commissions for the Napoleonic occupiers of Italy. Among other things, he was the artistic director of a copy of Leonardo's famous Last Supper. Bossi was also an art collector. He was particularly interested in Renaissance works, especially Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo. He was also involved in publishing the famous artist's vitae of Giorgio Vasari. The biography of Leonardo contained therein is today one of the oldest sources for Leonardo research. Bossi died of tuberculosis in 1815, the year of Napoleon's final abdication, aged only 38.

In the possession of the Galleria dell' Accademia

After Bossi's death, the print was initially auctioned off by his heirs. Seven years later, in 1822, it was acquired by the Viceroy of the Kingdom of Lombardo-Venetia, which was under Austrian rule at the time. Since then, the Vitruvian Man has been in the Galleria dell' Accademia in Venice. The print is rarely shown in public for conservation reasons.

Meaning - Angle, Shape and Proportion

The Vitruvian man is an illustration of human proportions, that is, he shows the geometrical relations of his external limbs.

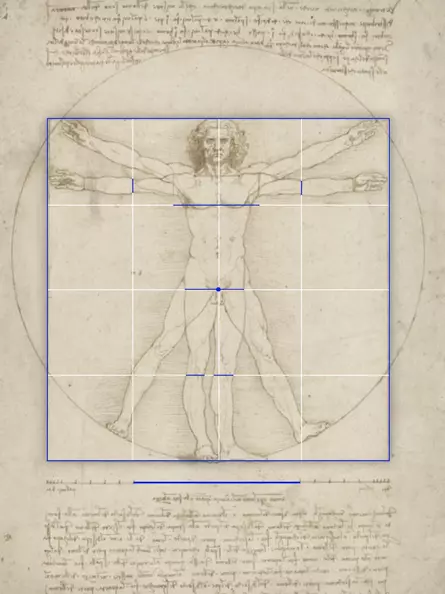

The scale

The line under the drawing functions as a scale for the proportions of the Vitruvian Man. The proportions of the drawing above are derived from its divisions. The scale is divided into 96 units of equal size, corresponding to the width of a finger. The division thus refers to the ancient Greek system of measurement. There, the width of a finger was considered the smallest unit of measurement. 96 finger widths corresponded to the width of a man with outstretched arms.

The scale is symmetrically mirrored in the middle, so that the lines on the left and right correspond to the usual length units on the forearm at the time of the Renaissance.

- the smallest unit is the width of a finger (far left)

- four finger widths are the width of a palm (without thumb)

- six palms make a cubit

A cubit (Ital. 'braccio') was a medieval measure of length. It meant the length from the elbow to the fingertips. In the Middle Ages, as in antiquity, measurements were made with standardised body units.

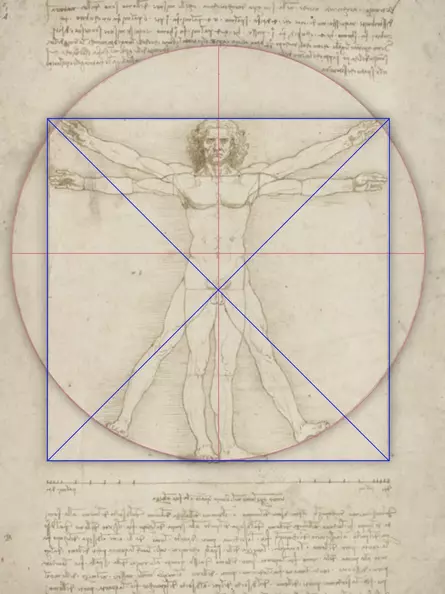

I The perimeter

Leonardo has the man raise his arms so that his middle fingers form a horizontal line with the height of the man's head (upper white horizontal).

- "If you open your legs so that they reduce your height by 1/14, and spread and raise your arms until your middle fingers touch the height of your head, you must know that the centre of the spread limbs is in the navel [...]".

The centre of the circumference is in the navel (blue dot).

The seventh

The feet are raised 1/14 of the height of the body (lower white horizontal line), that is half of 1/7.

- "From the crown of the chest to the roots of the hair is the seventh part of the whole man".

- "The foot is the seventh part of the man".

The lines of the seventh are highlighted in red.

The equilateral triangle

- "When you open your legs so wide [...] you must know that [...] the space between the legs is an equilateral triangle".

The man's spread legs form approximately an equilateral triangle (Mouseover).

Leonardo deviates twice from the text in the drawing. The feet are not at the same height because the right leg has been pulled inwards by about 5°. As a result, the height of this foot is not reduced by 1/14 (lower white line).

Since the right leg has been pulled inwards, the space between the legs is not symmetrical. This means that there is no equilateral triangle. For that, the right leg would have to be further up. The comparison becomes clear on mouseover. Why Leonardo deviated from the text in these details is unknown.

The sevenths cannot be transferred to the scale, because 96 finger widths cannot be divided by 7 without a remainder. This applies accordingly to 14.

II The quarters

The square around the man is the starting point of a continuous subdivision by bisections

The square

- "The length of a man's outstretched arms is equal to his height".

The sentence is the most famous of the sheet. It serves as the heading of the text in the lower part.

The half

The square around the man is divided horizontally into two halves

- "the beginning of the genitals marks the middle of the man".

The quarters

The half of the surrounding square is halved again to create quarters

- "From the nipples to the crown of the head is the fourth part of a man"

- "The greatest breadth of the shoulders contains within itself the fourth part of a man"

- "From the sole of the foot to below the knee is the fourth part of a man"

- "From below the knee to the beginning of the genitals is the fourth part of a man"

Leonardo made the quarterings visible by drawing lines on the Vitruvian Man (blue lines). They thus underline the observations made by Leonardo in the text.

The eighths

The quarters can be halved to form eighths, which appear around the head (red lines).

- "from the elbow to the armpit is the eighth part of the human being"

- "from the bottom of the chin to the top of the head is one-eighth of the height of the person".

Relation to the scale

The constant division of the side length of the square by 2 can be directly applied to the scale below the drawing. The blue line shows the half, to the left and right of it the quarters and if these were divided, it would be the eighths or the width of three palms. This proportion is called 1:2 or 2:1.

At this point it is noticeable that the drawing contains three misrepresentations.

- Leonardo writes: "From the elbow to the tip of the hand is the fifth part of the human being". However, he deviates from this and draws the distance from the elbow to the tip of the hand as a quarter (blue line at the elbow).

- The distance from the elbow to the armpit is not exactly the same on both arms. It is slightly shorter on the left side than on the right (mouseover, green line). As a result, the square around the head (one quarter of the man) has moved slightly to the left overall. The line at the left elbow has also moved slightly to the left

- the left and right sides of the surrounding square tilt upwards by about 0.3° towards the centre (mouseover, red lines). This makes the surrounding square look as if it is slightly tilted backwards or forwards in perspective.

Why Leonardo did not draw these lines as precisely as the others is unknown.

III The hands

The arms, held horizontally, are marked with longitudinal lines at the roots of the hands (black and white areas).

- "the whole hand is the tenth part of a man".

- "From the hairline to the underside of the chin is one tenth of a man's height".

From this it follows that a hand is as long as the face is high (black and white lines on the face). If the width of two hands is transferred to the lower scale, it is exactly 5/6 of a cubit.

It now becomes apparent that the longitudinal lines on the hands did not refer to the golden section of the forearm, but to the length of the hands, for here the length is now exactly the same, since it is not measured from the elbow but from the edge of the square.

However, Leonardo again deviates from the descriptive text. He writes that the hands are "the tenth part of the man", but he has drawn in the length of the hand with 10 of 96 finger widths, as can be read from the scale (black and white line correspond to the length of the hand and the face).

Leonardo therefore rounded off when he spoke of the tenth part: 10 of 96 correspond to 10/96 = 9.6 (~10).

IV Body height squared

Directly below the scale of the drawing, is this sentence, highlighted by centring:

- "The length of a man's outstretched arms is equal to his height".

The greatest width a man can span with his arms is at the level of the middle fingers, for they are the longest fingers. Both middle fingers of the horizontal arms form a line at the top of the chest. The distance of this line upwards is also subject to a proportion

- "From the top of the chest to the top of the head is one-sixth of a man's height".

The distance of this line to the end of the head has the same length as the width of the hip (white lines) and shows 4/6 of a cubit on the lower scale.

V Rotation points of the arms

[Translate to english:]

At the same height as the line drawn by the middle fingers there is a line below the chin (blue horizontal line). This is marked by two endpoints (blue dots on horizontal line). The length of the line on the scale is 3/6 of a cubit.

The end points could show the rotation point of the arms, but would then be anatomically wrong. Arms rotate at the shoulder joint in this case, but the points are too far inside for that. Leonardo must have known this from his anatomical studies and therefore probably did not draw any rotation points.

Symbolic angles

- From the two endpoints of the blue horizontal line, two lines lead at an angle of 22.5° to the middle fingers of the raised arms.

- from the centre of the square again a 22.5° angle leads down to the left shoulder (left white line)

- a 72° angle from the right shoulder upwards.

The 22.5° angle is created by dividing a 45° angle, which in turn is created by dividing a 90° angle. 90°, 45° and 22.5° are the midpoint angles of a regular 16-, 8- and 4-corner (i.e. a square).

The 72° angle is the centre angle of a regular 5-corner, which can only be constructed with knowledge of the golden section.

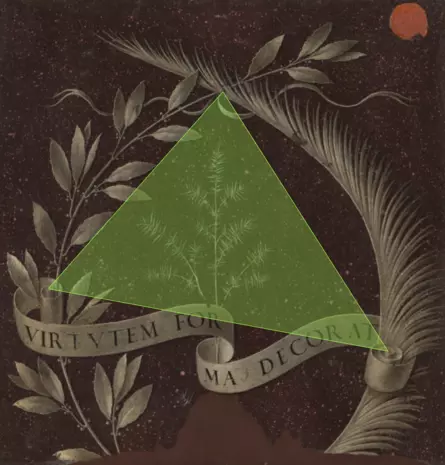

The golden section and right angle or their direct variations have a high symbolic value in classical geometry. It is therefore no coincidence that Leonardo emphasises precisely these angles around the head.

In the construction of his paintings, Leonardo almost exclusively combined the golden section (72°), square (90° angle) and equilateral triangle (60°) or their direct variations, as is the case here. The 60° angle, i.e. the interior angle of an equilateral triangle, is still missing. According to the accompanying text, this is supposed to span between the man's legs, but the angles deviate by 5° (I + mouseover).

Supposed disharmony of geometric relationships is typical of Leonardo's art, and serves to create tension when tracing his works. In this way, the paintings lead from one realisation to the next until a final harmonious picture emerges as the sum of all parts. It is therefore reasonable to assume that this work also conceals another hitherto unknown level.

The triangle of the middle parting and both eyes also shows the interior angles of 45°, 60° and 75

The triangle of 45°, 60° and 75° connects here the top of the bundle, as well as the centers of the spirals at the ends of the banner.

VI The face

- "The distance from the bottom of the chin to the nose and from the hairline to the eyebrows is the same in each case and, like the ear, is one third of the face".

The face can therefore be divided into thirds (white area). Between the eyebrows and the tip of the nose are the ears.

A third of the face, like the sevenths above, cannot be transferred to the scale without a remainder: The face has the length of 1/10 of the man's body height = 10/96, or 10 finger widths (smallest unit of the scale). If the 10 finger widths are now to be divided by three, one finger width would remain as a remainder. It is exactly the width by which the surrounding square is tapered upwards.

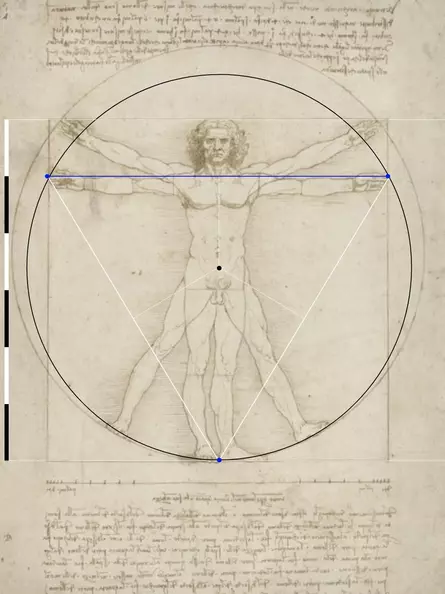

B Golden ratio

In the accompanying text Leonardo does not mention the Golden ratio, although it is an important insight from the drawing.

The vertical Golden ratio

- the centre of the surrounding circle lies very exactly at the height of the golden ratio of the square, i.e. in the navel (blue dot)

Furthermore, by steadily dividing the height of the body according to the golden ratio, it can be determined that the proportions of the human being can be depicted with the golden ratio (mouseover).

The horizontal golden section

The golden section can be shown in Vitruvian man not only in the height of the body, but also in the width of the body.

- the armpit lies in the golden section of the body width with outstretched arms (dark blue line at the right shoulder or upper horizontal line at the navel).

- If a cubit is divided according to the golden section, the golden section marks the transition between arm and hand (right blue and orange area)

- the length of a thumb divides the length of the hand also in the golden section (right and left, blue/orange line)

It is unclear to what extent it was Leonardo's intention to show the golden section, since he always hits his marks only approximately, more or less precisely. This also applies to the belly button, since its position cannot be identified exactly to the dot on the one hand, and on the other hand a human belly button is per se larger than a dot.

In addition, it can be seen that the left shoulder is slightly shifted to the left (green line), and this shoulder line is not in the golden section of the width of the surrounding square (recognisable by the lower horizontal line at the belly button). In addition, the transition of hand and arm on the left side is only very approximately divided in the golden section (black/white area). The length of the thumb, however, is here in the golden section of the length of the hand, as on the right side.

It can be seen that Leonardo, if anything, determined the golden section on the right side with greater accuracy than on the left side. The forearms and the area between the armpits are the same length according to the geometric scheme: 1 cubit on the scale.

Squaring the circle

The possibility of squaring the circle, i.e. constructing a square from a circle with the same area, has been a frequently studied topic in geometry since antiquity. According to classical Euclidean doctrine, this could only be done with the aid of an unmarked ruler and a compass. No case is known in which this was successful. Only approximate constructions were used. In 1882, the mathematician Ferdinand von Lindemann proved the impossibility of this construction.

Is the Vitruvian man a hidden construction sketch for squaring the circle?

Numerous notes and geometric drawings prove that Leonardo was concerned with the squaring of the circle. The quotation at the bottom of this page is just one example of many.

The reason for the assumption that Leonardo would have shown an approximate construction for squaring the circle in the Vitruvian man is probably due to his much-cited pleasure in creating riddles and hidden messages, which can also be found in his paintings, among other things. And probably because of the prominent importance of the circle and square on this study sheet.

According to this theory, Leonardo proposed the squaring of the circle as follows.

Coming soon

Historical significance

The sheet was first engraved by Carlo Giuseppe Gerli in 1784 and published in the work "Disegni di Leonardo da Vinci". Since then it has been accessible to the general public, but only known in the art-academic environment.

Study object for artists

Painters in particular used the sheet to learn how to paint people by memory. For if all people are based on the same proportions and differ only in their deviation from them, it is sufficient to remember only the deviation from the Vitruvian ideal, e.g. the slightly broader nose, slightly longer arms or slightly shorter legs. A drawing created in this way on the basis of universally valid proportions will bear a close resemblance to the original, even if the figure was not the direct model. This is what Leonardo suggests in his "Writings on Painting" and explains using the example of noses. Presumably, the facial features of the figures in his painting "The Last Supper" were created using this method.

The Rediscovery of Leonardo in Modernism

At the beginning of the 20th century, the popularisation of Leonardo da Vinci's complete works began. The initial cause was the media sensation caused by the theft of the Mona Lisa in 1911. As a result, the public began to perceive Leonardo not only as a painter, but also to take an increasing interest in the scientific and technical aspects of Leonardo's work.

Mussolini's Leonardo

Of international significance in this context was an international exhibition on the universal genius Leonardo da Vinci organised in 1939 by Fascist Italy under the dictator Benito Mussolini, in which Leonardo's engineering work was the main focus. Mussolini was keen to highlight Leonardo as the original inventor of the modern tank, the automobile and the submarine, as well as his ideas on the use of ballistic weapons.

The Vitruvian Man was also exhibited there and subsequently gained increasing public reception because of its simple and clear language of form, its style reduced to the essentials and its universal claim to represent an aesthetic principle that seemed to be eternal.

Le Corbusier's Modulor

In the 1940s, the important Bauhaus architect Le Corbusier took up the proportion studies of the Vitruvian Man. Based on this, he created his own system of proportions, the Modulor, which he used in most of his buildings.

Current use

Today, the Vitruvian Man is a symbol on every German health insurance card, the Italian 1 Euro coins and was or is a symbol for numerous scientific projects, for example NASA's Skylab 3 mission.

On the night of Saint Andrew I found the end of the squaring of the circle, and to the end was the light and the night and the paper on which I wrote, and to the end the hour.

Downloads

Sources

Website of the exhibiting museum: Galleria dell’ Accademia, Venice

Frank Zöllner, Leonardo, Taschen (2019)

Martin Kemp, Leonardo, C.H. Beck (2008)

Charles Niccholl, Leonardo da Vinci: Die Biographie, Fischer (2019)

Johannes Itten, Bildanalysen, Ravensburger (1988)

Frank Zöllner/ Johannes Nathan, Leonardo da Vinci - Sämtliche Zeichnungen, Taschen (2019)

Especially recommended

Marianne Schneider, Das große Leonardo Buch – Sein Leben und Werk in Zeugnissen, Selbstzeugnissen und Dokumenten, Schirmer/ Mosel (2019)

Leonardo da Vinci, Schriften zur Malerei und sämtliche Gemälde, Schirmer/ Mosel (2011)

Vitruvius' original text

Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture, Third Book, First Chapter

From whence the symmetrical relations are applied to the temples

- The construction of temples is based on symmetrical proportions, the laws of which must be most carefully observed by the architects. These, however, originate from symmetry (proportion), which the Greeks call analogia. Proportion is the harmony of the corresponding parts of the whole work and of the whole, from which the law of symmetry arises. For no temple can be justified in its construction without symmetry and proportion, unless, resembling a well-built man, it bears within itself a precisely executed law of arrangement.

- For nature has so formed the body of man that the face, from the chin to the top of the forehead and the lowest roots of the hair, constitutes the tenth part (of the whole length of the body); the same as much the surface of the hand from the wrist to the end of the middle finger, the head from the chin to the highest point of the crown the eighth part, as much from the lower end of the neck, from the upper end of the chest to the lowest roots of the hair the sixth, to the highest vertex about the fourth part of the length of the face more. But of the height of the face itself, from the end of the chin to the lower end of the nose is a third part, and likewise the nose from its lower end to that in the middle of the eyebrows; from this end point to the lowest roots of the hair, where the forehead is formed, is likewise a third part. The foot, however, measures the sixth part of the height of the body, the forearm the fourth, the chest likewise the fourth part. The other limbs also have their proportions, which were also used by the most respected painters and sculptors of old and have thereby achieved great and endless fame.

- In a similar way, the limbs of the temples must have proportions in the individual parts that correspond to each other in perfect harmony with regard to the total mass of the whole size. The centre of the body is by nature the navel. For if a man is laid on his back with his hands and feet stretched out, and the centre of the compass is placed in his navel, then, when the circular line is described, the fingers and toes of both hands and feet are touched by the line. Just as the figure of a circle is represented on the body, so that of a square is found on it. For if one measures from the lower end of the feet to the top of the head and transfers this measure to the extended hands, one will find the same width as height, as is the case with surfaces that are made square according to the angle measure.

- If, therefore, nature has formed the body of man in such a way that the limbs correspond to his whole figure in certain proportions, the ancients seem to have had good reason to establish it in such a way that they also observe an exact proportion of the individual limbs to the whole outer figure in the execution of buildings. Just as they handed down rules of order for all buildings, so they did especially for the temples of the gods, in which works merits and defects tend to be eternal.

- In the same way, they took the basic measurements, which seem to be necessary for all buildings, from the limbs of the body, such as the inch (finger), palm (palm), foot, cubit (elbow, forearm), and based them on a perfect number, which the Greeks call teleion. But as a perfect number the Greeks have determined what is called ten, for from the hands the ten-number of the inch (finger) is invented, and from the inch the palm, and from the palm the foot. But as according to the members of the two palms ten is the completed number, so Plato also approves of this number as the completed number, because tenness arises from the individual fingers, which are called monades among the Greeks. But as soon as they have become eleven or twelve, because they exceed them, they can no longer be a perfect number until they reach another ten, for the individual things are parts of that number.

- But the mathematicians, disagreeing with this, have said that the number called six is the perfect one, because this number has a division which corresponds to their system of calculation based on the number six, so in one they find a sextans (1/6), in two a triens (1/3), in three a semissis (1/2), in four a bes (2/3), which the Greeks call dimoiros, in five the quintarius, which the Greeks call pentamoiros, in six the perfect. When it grows to doubling, they find by adding one to the six the ephectos (1 1/6), it has become eight by adding a third; the adterlianus (1 1/3), which is called epitritos, has come into being by adding half nine; the sesquialter (1 1/2), which is called hemiolos, has come into being by adding two thirds of the tens; the besalter (1 2/3), which those call epidimoiros; in the number Eleven, because five are added, the Adquintarius (1 5/6), which they call Epipemptos; but Twelve, because it is formed of two simple numbers, they call Diplasion (the double).

- No less, because the foot is the sixth part of the height of man, and consequently the height of the body is determined by a number of six feet, they have set up this number as the perfect one, and perceived that the cubit also consists of six palms (handbreadths) and twenty-four inches. With reference to this, the states of the Greeks also seem to have done, that, as the cubit consists of six palms, they introduced in the same manner six copper coins, such as the aces, which they call obols, in the drachm, which some call dichalka, others trichalka, and quarter-obols, which some call trichalka, twenty-four to a drachm.

- Our ancestors, however, first adopted the old number and introduced ten copper coins to a denarius, and hence the denarius retains its name to this day, and they also called the fourth part, because it consisted of three and a half aces, Sestertius. Later, however, when they perceived that both numbers, six and ten, were perfect, they combined them into one and made sixteen the most perfect. As proof of this they put the foot; for if you take away two handbreadths from the cubit, there remains a foot of four handbreadths, but the handbreadth has four inches, and so it follows that the foot has sixteen inches and the denarius in copper has as many aces.

- If, then, it is agreed that number was invented according to the members of men, and that of the separate members there is a proportion of a certain part corresponding to the whole figure of the body, it follows that we must admire those who, in erecting the temples of the immortal gods, so arranged the members of their work that by proportion and symmetry their structure developed separately and, considered as a whole, uniformly.

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/f/csm_raffael-schule-von-athen_5726e8e83c.webp.pagespeed.ce.EMhUyGJ50I.webp)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/b/csm_leonardo-alle-gemaelde_2dc4b01ef6.webp.pagespeed.ce.ohfmgl8OfF.webp)