John the Baptist

John the Baptist is a painting by Leonardo da Vinci, painted in Rome between 1513 and 1516. John the Baptist was a New Testament prophet known for his austere lifestyle. He baptised Jesus Christ and preached of the coming Kingdom of God. He was imprisoned and ultimately beheaded. John the Baptist is the patron saint of Florence, Leonardo da Vinci's hometown. The painting is now in the Louvre in Paris.

And the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not comprehended it. A man appeared, sent by God; his name was John. He came as a witness to bear witness to the light, so that all might come to faith through him. He was not the light himself, he was only to bear witness for the light.

Leonardo da Vinci's paintings cannot be understood without examining the geometry of the picture

Leonardo da Vinci

about 1513-1516

Oil on wood (walnut)

56 x 73cm

Paris, Musée du Louvre

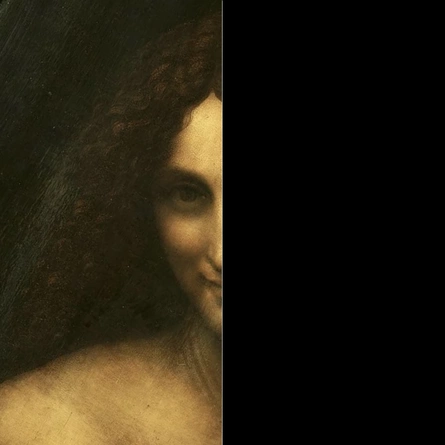

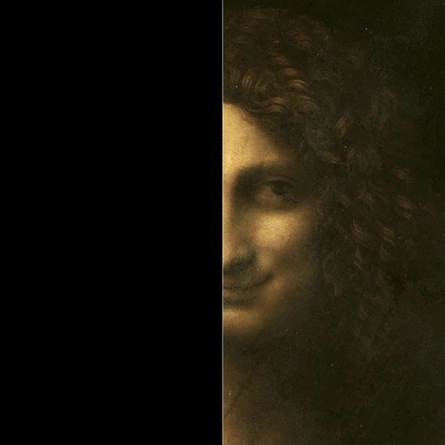

Image description

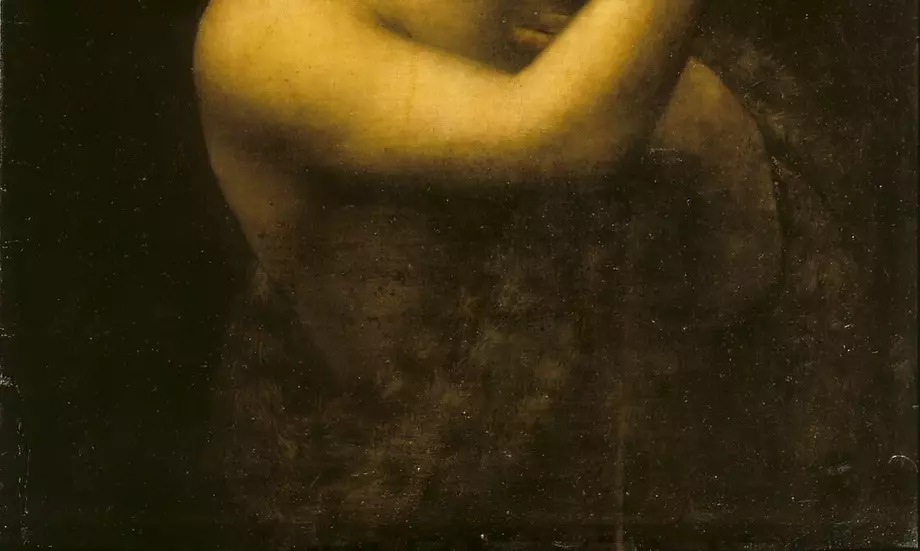

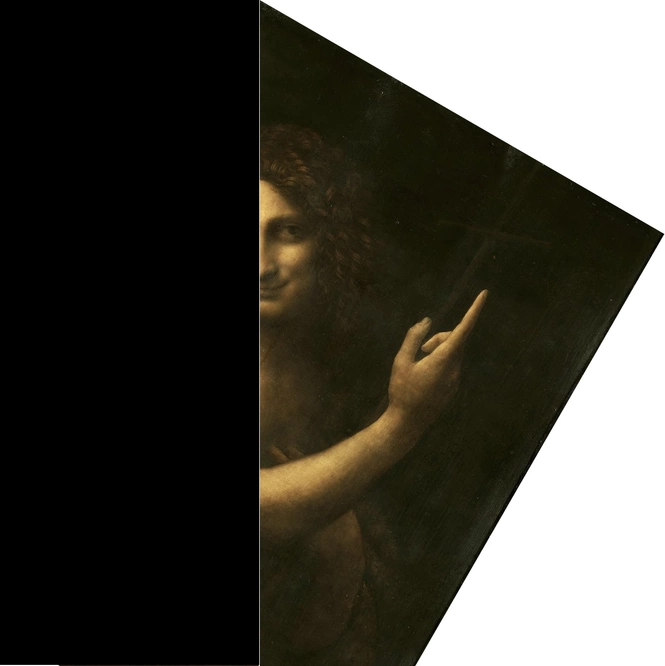

A naked young man with curly, shoulder-length hair. Illuminated by a light source outside the boundlessly dark room.

Around his waist is a cloak of spotted fur thrown over the crook of his left arm. In this leans a long cross that seems to reach to the floor. With the right hand upwards, pointing to himself with the left. A smiling face.

Who was John the Baptist?

The long cross staff and the scanty clothing of a fur cloak are the iconographic attributes of John the Baptist.

John the Baptist is a biblical figure of the New Testament. He is considered by Christians to be the last of the prophets. His mother was Elizabeth, a relative of Mary, the mother of Jesus. Having grown up, John preached in Israel at the turn of the age about the approaching Kingdom of God: "He who comes after me is ahead of me, because he was before me" and exhorted people to repent.

He lived very modestly, clothed himself with a coat of camel hair and fed on locusts and honey. The Jews revered him as the new Elijah, one of their most important prophets, and were baptised by him. He also baptised Jesus and later recognised in him the expected Messiah.

John loudly lamented the sinful life of the Jewish king Herod. He saw it as wrong that Herod married the widow Herodias after the death of his brother. For this, John was arrested as a rebel and thrown into prison.

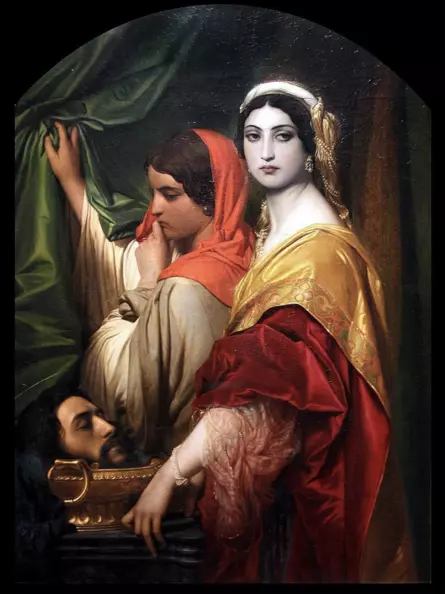

King Herod had a beautiful stepdaughter. To persuade her to dance, he granted her wish and had John the Baptist beheaded. His head was handed to her on a bowl. John was then buried by his followers.

John the Baptist is not to be confused with:

- John, the disciple of Jesus and one of the twelve apostles.

- John, the author of the Gospel of John

- John, the author of the Revelation of John

St. John's Day and Christmas

John the Baptist is one of the most important figures in the New Testament and thus also in the church year. This is especially evident in the fact that Christmas, the celebration of the birth of Jesus, is celebrated on 24 December, three days after the winter solstice (21 December).

Whereas the Feast of St. John, the festival in honour of the birth of John the Baptist, is celebrated on 24.6, three days after the summer solstice (21.6). The two birthdays are therefore exactly half a year apart, which highlights the reciprocity of the two figures most strikingly.

Patron Saint of Florence

Leonardo da Vinci's biography is closely linked to this city. He grew up and was educated in Florence, his father lived in the city and it was there that he took on his first commissions. Although Leonardo left Florence when he was about 30, he returned there again and again later.

Representations of St. John in Painting

The stations in the life of John the Baptist, which are listed in the New Testament, have often been the subject of paintings in the history of painting: Jesus and John playing as boys, John in the desert, John preaching, the baptism of Christ and finally the beheading.

In addition, iconographic representations of Saint John the Baptist in numerous variations were very common. Leonardo's painting falls into this category.

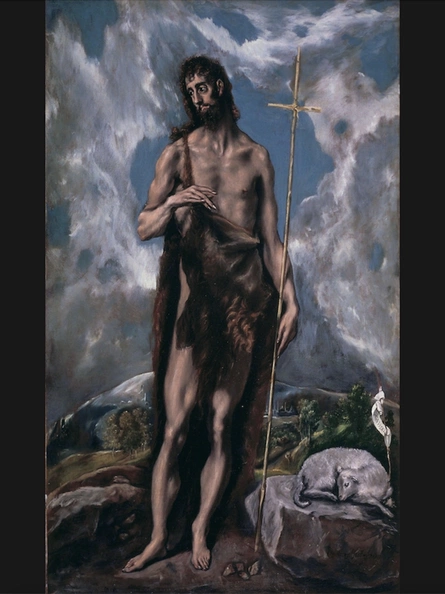

John and Jesus as boys

Exemplary iconographic representation with fur, cross staff, lamb and a white banner with the inscription "Ecce Agnus Dei" ("Behold the Lamb of God").

Symbolism

Although the painting at first appears to be clearly understandable due to its simplistic return to the essentials, the work quickly becomes more complex upon closer inspection.

Quite fundamentally, the work was painted to be contemplated in silent devotion. It is therefore a contemplative painting. Viewers are to be reminded of the biblical word, the Christian faith, and John's willingness to sacrifice. For a religious devotional painting, it is surprising that the characteristic cross of Christianity is barely visible against the darkness of the background.

The light

The light is the central motif of the painting and refers to the Gospel of John.

"A man appeared, sent by God; his name was John. He came as a witness to bear witness to the light, so that all might come to faith through him. He was not himself the light; he was only to bear witness to the light." (John 1:6-8)

What is meant by the light is explained elsewhere in John's Gospel:

"When Jesus spoke to them another time, he said, "I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life." (John 8:12)

So Leonardo here shows John the Baptist, who, knowing of the coming of the hoped-for Messiah, points to the one who will come after him. The Baptist must have seen the "light of the world" just now, because it illuminates his face from obliquely above. Observers cannot see the source of the light; it lies outside the pictorial space. John's smile appears blissful in this context, for the light of the world offers him confident salvation in the darkness of unbelief that surrounds him.

The finger pointing

The upward pointing index finger does not point directly to the cross, but points upward. Superficially Leonardo surely refers with it to the coming of the Messiah, the "light of the world", which will appear sent from the divine sky on the earthly earth.

In the second derivation the gesture must refer likewise to the biography of John. For Leonardo shows the Baptist illuminated by a dungeon window in the darkness of Herod's dungeon. He seems to already anticipate his imminent execution, because with one hand he points to his chest, which in the sign language of all cultures always means "I". The fact that the Anabaptist conspicuously bows his head to the side and exposes his neck shows that he already knows how he will die. He will be beheaded in the dungeon. In the Christian context, the upward pointing finger points to the kingdom of heaven.

So the prophet's gesture means, "I will die by beheading and go upward, into the kingdom of heaven." Believing in Jesus as the Messiah, John could not feel fear of death, because faith in Christ promised eternal life. Therefore, John can smile in the face of the certainty of his sad fate and is not saddened to death.

The pointing finger in Leonardo paintings

Leonardo was the first to paint John the Baptist with the characteristic upward pointing index finger. All painters who came after him adopted this style of depiction.

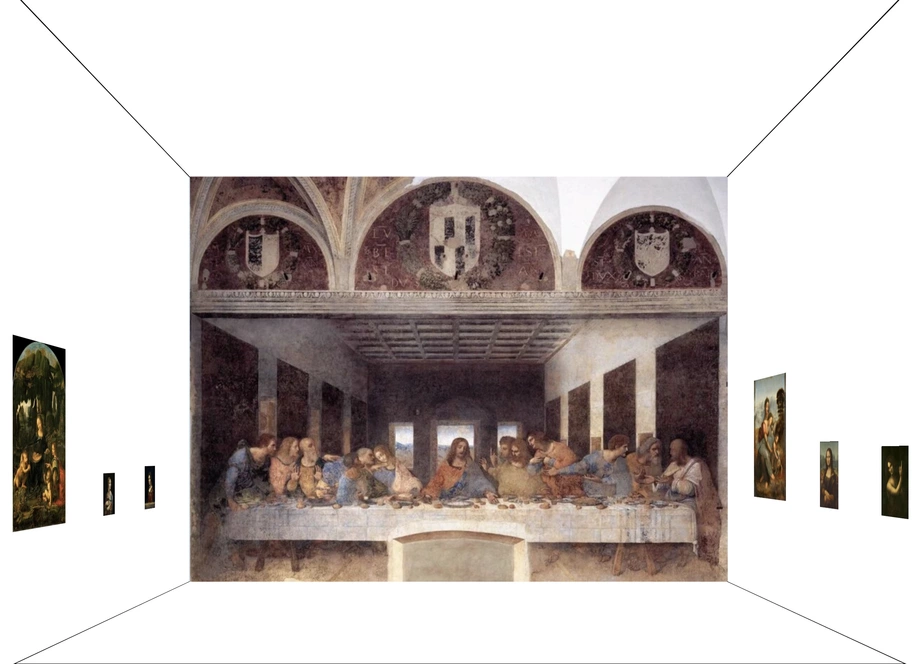

Leonardo used this hand position in only three of his completed paintings.

- The Madonna of the Rocks, Leonardo's first completed work shows John the Baptist and Jesus as children. The angel points to the Baptist with this hand position

- the Last Supper, Leonardo's central major work shows one of Jesus' 12 disciples with his index finger pointing upward. It is the disciple whose head is closest to that of Jesus'

- John the Baptist, Leonardo's last painting shows the adult John also with his index finger pointing upwards.

On the one hand, Leonardo thus impressively demonstrates how three fundamentally identical hand positions can change their meaning depending on the context. On the other hand, it cannot be denied that Leonardo reveals a pattern in the chronological order of his paintings via precisely this optical similarity: the typical hand posture is found on the first, the middle, and the last of Leonardo's completed and doubtlessly genuine paintings.

The Madonna of the Rocks, as the first independent completed work, shows the well-known gesture in the figure of the right angel. To the right, the portraits of the Lady with the Ermine and that of the Belle Ferroniere. The 9m wide Last Supper, Leonardo's central major work, shows a disciple with the same hand posture as in the Madonna of the Rocks, only this time the index finger is pointing upwards. To the right is Anna Selbritt and the Mona Lisa. Leonardo's last painting of John the Baptist also shows the already familiar hand posture. The first and last paintings are the only ones to show John the Baptist. The first painting shows John as a child, the last, painted about 30 years later, shows John as an adult.

First completed and undoubtedly genuine painting. The hand of the angel points to the Baptist

The central major work. The hand of the disciple whose head is closest to Jesus

Last completed and undoubtedly genuine painting. The hand of the Baptist

The cloak of the Baptist

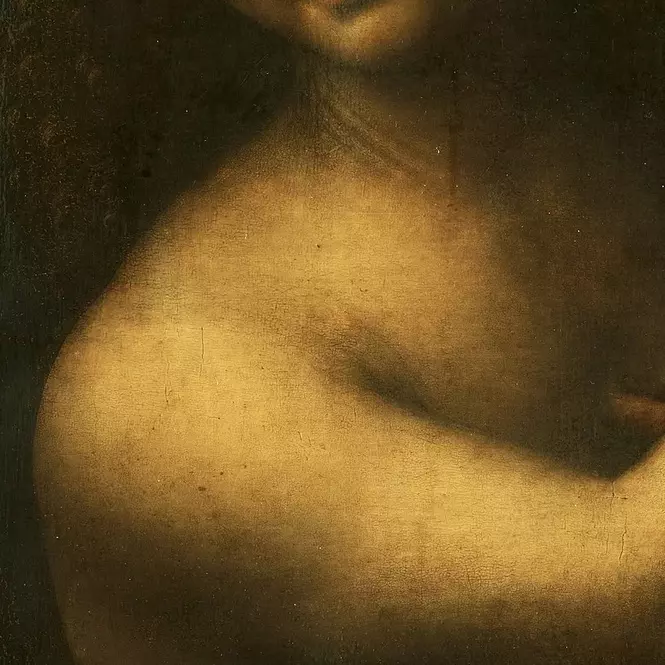

The depiction of John the Baptist's cloak is special in two ways. Firstly, John wears the cloak in the style of an ancient Roman toga, and secondly, the material of the cloak is obviously not the hide of a camel, as John is said to have worn it.

The toga of the Baptist

John the Baptist wears his cloak in the manner of a toga, according to ancient Roman models. The toga was a fabric several meters long that was artfully wrapped around the body according to various fashions. The fabric usually hung loosely over the left arm and the right shoulder was usually left bare. The toga was only allowed to be worn by Roman citizens and differed in color, material and decoration depending on social status. Usually the tunic was worn under the toga. A short- or long-sleeved top that reached to the knees and was fastened at waist level with a belt. Depending on the temperature and the occasion, the tunic could be dispensed with, leaving the right arm and shoulder unclothed, as in the case of Leonardo's Anabaptist.

Especially during public speeches, the Romans considered it particularly elegant to always hold the left hand in front of the stomach. Leonardo's John therefore also adopts this pose to emphasize his work as an eloquent preacher.

The yellow toga of the poet Horace is wrapped in the style of Leonardo's Baptist. Under the toga Horace wears a white tunic

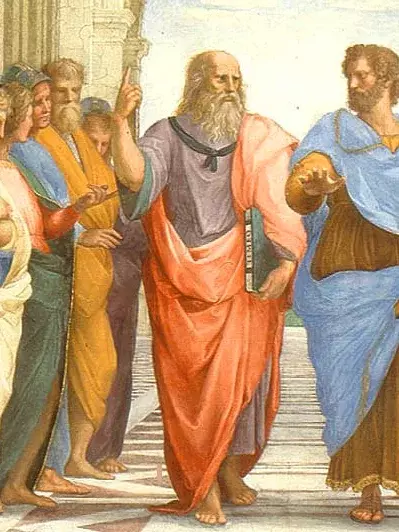

Raphael, who was about 30 years younger, knew Leonardo personally and admired him greatly. His most famous paintings are consistently inspired by Leonardo. Here he shows Leonardo as Plato wearing a toga. He raises his index finger in the manner of Leonardo's Baptist. Raphael's painting was probably done shortly before Leonardo's John the Baptist, but after The Last Supper and The Madonna of the Rocks, where this striking gesture is also shown

The coat of the ermine

Even if the shape of the cloak is based on a toga, the material is not. Usually a toga was made of wool, not fur.

Like the cross, the pattern of the fur can only be seen in the darkness of the room when looking closely. John the Baptist, according to the Bible texts, actually wears a coat of camel hair. But the regular, spotted black spots do not at all speak for the fur of a camel, but remind of the fur of predatory cats, e.g. that of leopards or cheetahs. For this, however, the coat of the cloak is basically too dark and the spots too evenly distributed.

Ermine coat - symbol of wealth and power

It is highly probable that Leonardo shows a plush cloak made of the reddish-brown summer fur of stoats, to which, according to the fashion of the time, their black tail tips were added at regular intervals.

The ermine fur in the arms of the Baptist repeats a motif from a previous Leonardo painting. He had made a portrait of Cecilia Gallerani in 1491, known as Lady with an Ermine. She was the mistress of Leonardo's long-time employer, the Milanese Duke Ludovcio Sforza (nickname: "White Ermine").

The white ermine in the winter coat. It is depicted twice as large as in reality

The inside of the red coat is lined with the white winter fur of stoats. The attached black tail tips are clearly visible

Ermines have a white coat in winter, but a reddish-brown coat in summer. The tip of the tail always remains black. Coats made from the fur of stoats became very popular among the nobility from the Middle Ages onwards. The nobility could easily identify with the animals: Ermines were brave fighters, extremely fertile and their pure white winter fur made them appear very virtuous. Even today, all coats of arms of the European high nobility show a white coat of arms made from the winter fur of stoats with the typical attached black tail tips. The English royal crown (Edward's crown) is also decorated with stoat fur. Although the nobility usually wore coats made of the white winter fur, coats made of the brown summer fur were not uncommon.

Why does the humble John wear such a precious fur?

Wearing ermine fur was already reserved for the high nobility for reasons of cost. The costly fur would thus identify Leonardo's Baptist as a nobleman of high rank. It is surprising why John the Baptist, described as poor and humble, is depicted wearing such a valuable fur and raises the question of whether Leonardo really only wanted to create a religious work here. Did Leonardo use the religious motif of John the Baptist at the same time to create a monument to his rich and powerful hometown of Florence?

For John the Baptist has always been the patron saint of Florence. This gives rise to the assumption that Leonardo has created a personification of his hometown Florence here, which in a certain way also represents his alter ego. For the rise of the city, especially the rise of the rich Florentine banking family Medici, is closely linked to Leonardo's biography.

The Rise of the Medici Family

Leonardo painted the picture in 1513 at the court of the Medici Pope Leo X (Giovanni de' Medici). The long-established Florentine Medici family had attained enormous wealth first through international trade and later through banking. The Banco Medici was one of the first of its kind in Europe and lent money to kings, princes and bishops, among others. For decades, the Medici were by far the richest family in Florence and at times even the richest non-noble family in Europe. The Medici's political influence was correspondingly enormous. All political decisions in Florence could only be made with them, or against them.

With the coronation of the head of the family, Giovanni de' Medici, as Pope Leo X, the Medici family, originally only bourgeois, became part of the higher nobility. By being elected pope, Leo X had become not only head of the church but also king of the powerful church state, which at that time encompassed all of central Italy. The Medici Pope subsequently cemented his family's power by granting hereditary titles of nobility and feudal estates; for example, he appointed three of his closest relatives as dukes.

The Medici systematically expanded their power. Luigi de' Rossi and Giulio de' Medici, depicted here, were cousins of the Pope and were first elevated by him to the rank of Cardinal. Giulio (left) was also elected Pope in 1523 as Clement VII.

Giuliano de' Medici asked Leonardo to the papal court and was Leonardo's patron from 1513 until his early death in 1516

John the Baptist as a symbol of Florence's power

Florentine merchants were active everywhere in Europe and the Florentine banks were the financially strongest financial institutions of the time. Therefore, the florin was the most important trading currency in Europe, disproportionately widespread and a comparison with today's world reserve currency, the dollar, is quite appropriate. The florin was a coin made of pure gold and showed a lily, the coat of arms of Florence, on the obverse. On the reverse, the coin showed the patron saint of the city of Florence, John the Baptist.

The small gold coin weighed 3.5g. It was widespread throughout Europe and can therefore be described as the dollar of its time. The coat of arms of the city of Florence is depicted on the obverse. On the reverse the patron saint of the city, John the Baptist

The octagonal Baptistery of San Giovanni (foreground) is dedicated to St John the Baptist, as is every baptistery, and is located next to Florence Cathedral (background of picture). The dome of the cathedral was completed during Leonardo's apprenticeship with Verrocchio, who made the 2m gilded sphere on top. The dome was the largest in the world until the 19th century

The Rise of Florence

Against this background, it now becomes clearer why the modestly living John the Baptist wears a cloak made of the precious fur of the ermine in Leonardo's work.

As the patron saint of Florence, John the Baptist was a figure of identification for all Florentines. His image was on every gold coin from Florence, and he was the patron saint of numerous buildings in the city. With Florence's rise to become the most financially and culturally prosperous city in Europe, the Florentines' pride in their achievements grew, culminating in the election of Leo X as Pope in 1513. In the same year, the pope's brother brought Leonardo to the papal court in Rome. Like Florence and the Medici, Leonardo was at the peak of his creative powers, 6 years before his death. He knew that a work of John the Baptist could not show only the religious aspect. Rather, Leonardo had to create a symbol that would be an impressive testimony to the creative power of the Florentine citizens for posterity.

Leonardo has not only painted St. John in a religious sense, but has also created a symbol of the prosperity of Florence, specifically a symbol of the religious, financial and cultural rise of the city. The elegance with which Leonardo sets the ermine fur (symbol of wealth) and the cross (symbol of papal power) in the background in terms of colour is due to the respect for the actual religious content of the picture and thus for the main character of the painting, John the Baptist.

The squinting eyes

Due to the strong light-dark contrasts and especially the weak illumination in the area of the eyes, a striking detail of the painting can easily be overlooked: John's eyes are looking in two different directions b.

This becomes particularly clear when the painting is rotated so that John's head is positioned vertically. To do this, the painting must be rotated by exactly 30°. If the left and right halves of the face are now covered alternately, it becomes clear that the left eye is looking directly at the viewer, whereas the right eye is looking exactly at the centre of the cross. This underlines the religious character of the painting. John is smiling at the viewer because he is looking with confidence at the symbol of the Christian faith, the cross.

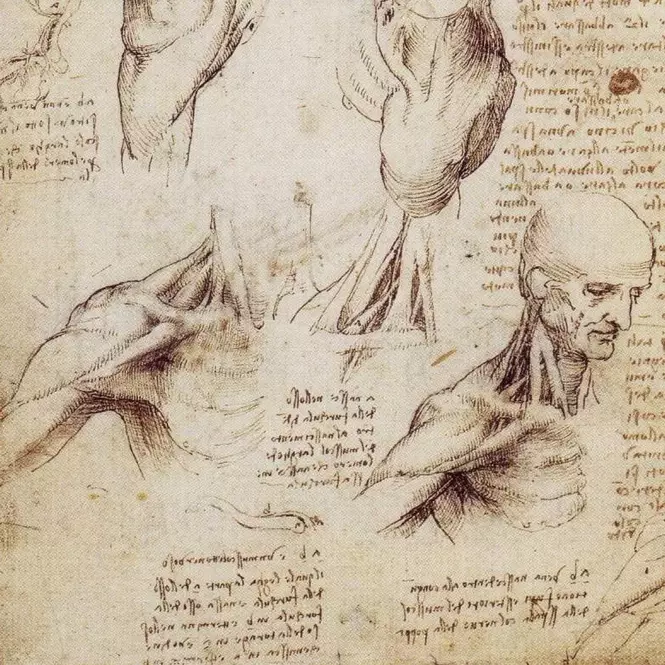

The Anatomical Aspect in Leonardo's Paintings

Regardless of the religious interpretation, in the anatomical sense the different directions of the eyes are a misalignment of the eyes, the so-called strabismus. Leonardo had a very extensive anatomical knowledge. He dissected at least 30 corpses, made the first precise anatomical drawings of them and researched the causes of diseases.

Leonardo always hinted at his anatomical knowledge in his paintings. For example, his portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, the "Lady with the Ermine", shows a conspicuously swollen left hand, which is not atypical for heavily pregnant women. Cecilia Gallerani became pregnant in the course of the painting's creation. The Mona Lisa, painted about ten years later, shows two visible diseases, a xanthelasma on the eye and a lipoma on the hand. But John the Baptist also shows another anatomical abnormality in addition to the squint. Leonardo has anatomically exaggerated the area around the right collarbone. The area from the right shoulder blade to the collarbone is not sufficiently curved inwards. Against this background, these imperfections of painterly perfection must be seen as allusions to Leonardo's anatomical knowledge.

The lady's left hand, lying on her stomach, appears swollen. Probably an indication of her pregnancy at the time of the painting's creation

The yellow spot on the right nasal bone is a xanthelasma, a deposit of fat or fat-like substances (cholesterol) in the skin, usually occurring around the eyes

The prominent bump at the origin of the right thumb is probably a lipoma, a usually benign fatty tumour

The Baptist is missing his collarbone. The prominent bone between the shoulder and sternum should stand out clearly under the skin in this position

Based on his knowledge of human anatomy, but above all on his study of the movement of muscles during a movement, Leonardo must have known that in a movement such as that performed by John the Baptist, the collarbone must stand out more clearly

Two faces

Since both eyes look in two different directions, the face of the Baptist can be understood as two different faces that have been put together along an imaginary line along the bridge of the nose to form one face. In fact, two halves of the face are created in this way, one on the left and one on the right, each showing typically feminine and typically masculine ideals of beauty respectively.

- large, round eyes

- high cheekbones

- narrow nose

- a narrow face running upwards

- voluminous long hair that also reveals a bare shoulder

- eyes looking up from below (women are usually smaller than men and therefore often have to look up at men)

- pronounced facial muscles

- prominent chin

- prominent lower jaw

Woman and man at once

The centre line must run along the tip of the nose and divide the face there as shown here; it cannot run further to the left or further to the right. It is therefore undoubtedly the case that Leonardo has merged a female and a male half of the face into one, but this is hardly noticeable due to the inclination of the head, the strong sfumato and, not least, Leonardo's unique painterly skill. This fusion of the two faces into one gives many viewers the impression of an androgynous person, from which they then simultaneously conclude that Leonardo has homosexual tendencies. Yet Leonardo merely demonstrates, in his typical enigmatic playfulness, how easily human perception can be deceived. He applies this game with perception just as masterfully in another painting from his late work, Anna herself. There it is Anna who appears strikingly masculine.

Anna's posture is not the only reason why she appears much more masculine than Mary sitting on her lap. With this trick Leonardo succeeds in uniting two different subjects in one scene. On the one hand, that of the Holy Family consisting of Joseph, Mary and the Child Jesus, and on the other, that of Anna Selbdritt (Old German for 'three') consisting of Anna, Mary and the Child Jesus

Further interpretations

It is clear from the foregoing, and this is typical of Leonardo and makes his painting so unique, that he was able to superimpose several levels of interpretation and combine them into a single painting. In addition, the following possible interpretations are often mentioned:

- Thus, some see in the painting a final greeting from Leonardo, who painted his final painting (a + mouseover) and is now taking his leave into the darkness, combined with the hope for an ideal heir to come after him. Just as Jesus came after the Baptist

- Others see the gesture of pointing fingers as an expression of Leonardo's lifelong dream of ascending and flying into the sky

- Still others suspect Leonardo's homoerotic longing in the depiction of the half-naked Baptist, which they perceive as Venusian and androgynous

- Some see the work as a joke by Leonardo, who in his final work manages to create such a perfect illusion of a figure that viewers only have to be reminded by pointing to the picture frame that the illusion is actually just a painted wooden panel. This kind of humour would be typical of a Leonardo painting

Geometric analysis

This analysis presupposes knowledge of the symbolism of Euclidean geometry and the significance of the golden section.

The painting has clear geometric references, typical of a Renaissance work. Leonardo uses a system of symbolic angles, proportions and figures, which he combines masterfully. The geometry is not an end in itself, but underlines the meaning of the work. Thus Leonardo's Baptist preaches about geometry and the advantages of painting over poetry and music, he is decapitated by a geometric construct, geometrically rejuvenated and finally the question is clarified whether and how Leonardo signed this work.

Moreover, due to the central role of the cross in the construction of the picture, it will be shown that it is very unlikely that the cross-staff was added later. This is a debate that is still going on in expert circles today. It raises the question of how religious Leonardo was and whether he could have deliberately omitted the cross. For without the cross, the sitter would merely be a naked young man with a coat around his body, which would emphasise the erotic character of the work.

I The Cross of the Baptist and the Golden Section

It is often noted that the Baptist seems to be speaking, that he was captured by Leonardo at the moment of admonition: "Turn back! For the kingdom of heaven is at hand" (Mt 3:2). Here, the darkness surrounding him is interpreted as the desert, which figuratively stands for unbelief in the world. Accordingly, his pointing finger points to the coming Messiah who is greater than he: "But he who is coming after me is stronger than I, and I am not worthy to take off his sandals".

The preachy overall expression cannot be denied, only the mouth of the Baptist is closed. Why Leonardo leaves the Baptist silent becomes clear through the geometric connection of face, posture and cross staff.

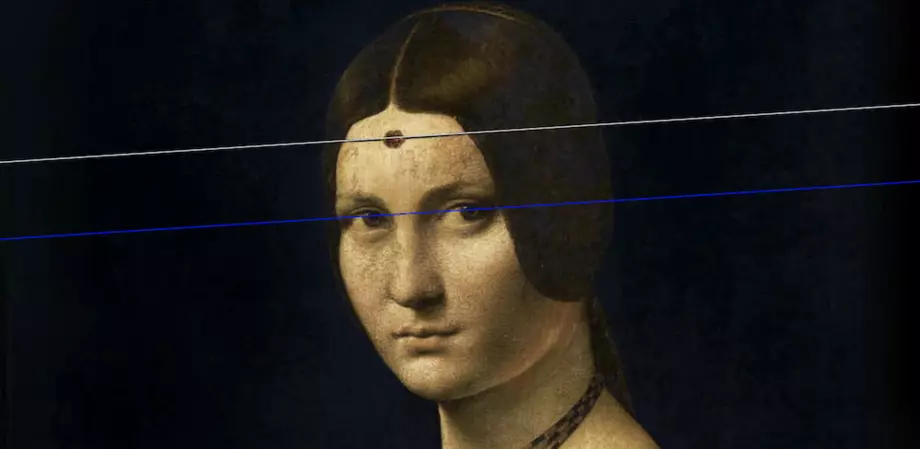

- The horizontal of the cross that John the Baptist holds with his left hand is inclined at an angle of 18° (blue line). The vertical of the cross is tilted at a 3.5° angle and thus refers to Leonardo da Vinci's painting Belle Ferroniere. This angle also appears there. On the one hand as the angle of inclination of the ferroniere, on the other hand in the direction of view of the Belle Ferroniere.

Both the angle of inclination of the ferroniere (headband, white line) and that of the eyes (blue line) correspond to 3.5°.

- The Baptist's left eye is in the golden section of the width of the picture. The mouth lies in the golden section of the picture height (orange lines).

- Starting from the upper right corner of the picture, a straight line at an angle of 30° intersects the centre of the cross and both eyes of the Baptist (top yellow line).

- From the left eye an 18° angle leads to the tip of the index finger (middle yellow line). This line runs parallel to the blue horizontal of the cross.

- From the tip of the index finger, a 30° angle leads through the intersection of the horizontal and vertical golden sections at the Baptist's mouth.

- The impression of a three-dimensional coordinate system is created (mouseover, white lines).

Interpretation

Due to the parallelism of the oblique lines and their intersections at important elements of content (cross, eyes, mouth and index finger), it can be said with certainty that Leonardo has defined a sequence here. On the left side, the eye and mouth are emphasised, on the right the index finger and cross. The eyes are the sense organs for perceiving light, the mouth is the instrument of the word. The cross places this in a religious context, the index finger hierarchises by pointing upwards.

Paragone

Since antiquity, there has been a competition of the arts, also called a paragone, which was conducted directly by comparing works of art of different genres, but more often indirectly by means of theoretical disputes. Leonardo took an active part in this and explained in his writings why he preferred painting to other arts such as literature - the written word - or music. His core argument was that painting can present all the information at once, whereas a word narrative or a piece of music only emerges gradually.

The connection to the Paragone becomes clear through the construction of the picture. Leonardo uses geometry to establish a hierarchy of the senses and related arts. The yellow line leads from the left edge of the picture to the mouth (symbolic of the spoken word, sense of hearing), to the index finger (sense of touch) and to the eyes (sense of sight). Then to the symbol of the cross, here in the meaning of conscious being independent of present sensory perceptions, i.e. the mind, towards the darkness in which everything begins.

Leonardo then also demonstrates with the painting that, without having to use words, he can show in a flash what John the Baptist is preaching about.

It is difficult to achieve the same with words, if only because listeners, based on their individual experience, imagine a different person under John the Baptist. Leonardo's work, on the other hand, has the quality of unifying the idea of the Baptist, which must exist because there was only one Baptist. Through the ability of painting to carry out this unification, he lays claim to primacy in the Paragone for painting.

That Leonardo uses a depiction of John the Baptist for the Paragone is not accidental. In the eponymous Gospel of John in the New Testament, the very first sentence reads: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God" (John 1:1). This sentence refers to the beginning of the Old Testament: "God said, Let there be light. And there was light" (Gen 1:3). So God spoke first and then created the light. In terms of the Paragone, this statement is about prioritising seeing and speaking, and what came first. Leonardo once again positioned himself on this question with his work.

II The beheading of the Baptist with geometric means

An essential aspect of the John the Baptist narrative, apart from the baptism of Christ, is the beheading of the prophet. When looking at the painting, a sense of its end already emerges. Leonardo achieves this through some compositional tricks

- The head, which is too small for the body and has shifted slightly to the left between the shoulders, is striking. In this way the head does not seem to belong to the body.

- the head is also conspicuously tilted to the right, which distinguishes it from other Anabaptist representations. This resembles the posture of someone who has bared his neck.

- Leonardo has also anatomically exaggerated the area around the right collarbone. The area from the right shoulder blade to the collarbone is not sufficiently curved inwards. The area looks like a flat surface, e.g. a tray.

- The index finger and right shoulder set strong points of light which form a line below the head of the Baptist.

Depictions of the disembodied head of the Baptist on a tray, along with depictions of Christ's baptism and iconographic depictions, have been widespread since the Renaissance (Cranach, Caravaggio, etc.). Due to the popularity of this depiction and the optical stimuli Leonardo sets, the viewer cannot help but look for the line where the head of the Baptist separates from the body. Leonardo defined this according to geometrical rules.

- The Baptist's left eye lies in the golden section of the picture's width. The mouth lies in the golden section of the picture's height. From their intersection a 30° angle leads to the raised index finger of the right hand (grey lines).

- A horizontal line intersects the Baptist's left eye and is tangent to the tip of the raised right thumb (white line).

- A parallel can now be drawn from the thumb to the line from the index finger to the mouth (oblique grey and red line). This runs from the thumb exactly under the chin of the Baptist and is tangent to the shoulder at the base of the neck.

In this way, the beheading of John the Baptist is added to the pictorial narrative by geometric means. What is at first only a hunch is confirmed by the geometry exactly and as a deliberate hint by Leonardo.

III The coordinate system

If a three-dimensional coordinate system was already introduced in I - golden section of height and width, plus a straight line through its point of intersection with the index finger at an angle of 30° - Leonardo extends this purely mathematical model by another one that implies a physical interpretation.

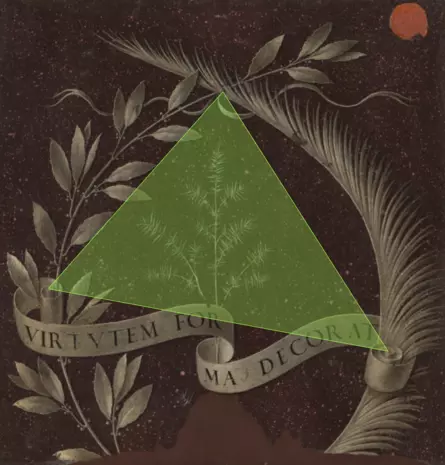

- The middle parting and both eyes form a familiar triangle with the symbolic inner angles of 45°, 60° and 75° (transparent triangle). Leonardo used this in all his portraits

Triangle with the corners of the middle parting and the eyes. It has the same symbolic inner angles as in the Baptist

The triangle here connects the top of the bundle, as well as the midpoints at the end of the banner. The order of the angles is different, which changes the outer form

- From the centre of the cross (dark blue lines) a 75° angle can be drawn to the crook of the Baptist's arm (light blue line). From this line to the left to the shoulder the 90° (85°) and to the right to the forearm the 30° (27°) are just missed (light blue lines left and right).

- From the crook of the arm, a 60° angle leads upwards to the left to the forehead (white line). This line runs exactly over the tip of the Baptist's nose, but without hitting the middle parting.

Only now does one notice that the centre parting of the hairstyle is not centred, but shifted to the right side. This makes the hair look more like a wig.

- From the centre parting, a 60° angle leads back to the crook of the arm (light red line), but does not run exactly over the nose and misses the crook of the arm slightly to the right. Both lines, light red and white, are thus related to each other. They both start from a centre point and drift to the right towards the target.

The arrow and a kiss

If one understands these lines and the triangle as a unit of meaning, another pictorial element emerges, a geometric arrow pointing upwards to the left (transparent triangle and white and light red line).

Together with the light blue lines, the impression now arises, as in I, of a three-dimensional coordinate system tilted forward to the right. Only this time the centre is different. It is no longer in the mouth, as in the first from I, but in the crook of the arm.

At this point, the viewer cannot help but realise that it seems mathematically nonsensical to place one coordinate system in another. This leads to the idea of merging the two centres. In this case, this would mean bringing the crook of the Baptist's arm to his mouth, just like children in love do when they kiss. In conjunction with the childlike, mischievous expression on the Baptist's face, Leonardo seems to be at least hinting at the childlike playfulness of John here, in addition to the subjects already shown - iconographic representation, John in the desert, sermon and beheading.

That the arrow representation is not an arbitrarily chosen geometric relationship becomes clear through a whole series of other dependencies.

The mirrored triangle

In addition to the pointed end of the arrow, two other triangles have been created in relation to the y-axis of the new coordinate system (long light blue line).

An equilateral right triangle with interior angles of 90° and 45° (mouseover, yellow triangle).

the triangle on the forehead is mirrored and enlarged almost exactly three times (blue triangle). The mirror axis runs along the golden section of the bidl width through the Baptist's left eye.

The tetrahedron

If the lines of the front triangle are extended downwards, left to the right armpit and right to the lower side of the blue triangle (white lines), a three-dimensional figure is created. The red lines, together with the white and light red line in the middle, form the front view of a tetrahedron, slightly distorted in perspective. The tip of the arrow is thus also the tip of the tetrahedron.

Leonardo also used the tetrahedron to compose Anna and Maria in the painting Anna Selbdritt. There, Anna and Mary are arranged in the shape of a tetrahedron.

IV Leonardo's Signum

Painters were still considered craftsmen at the time of the Renaissance. Thus they were also organised in guilds that represented them in their affairs. Leonardo had been a member of the Guild of St Luke (Compagnia di San Luca) in Florence since 1472, named after the Evangelist. The paintings themselves were furnishings for the patrons, such as furniture, in some places already valuable assets for the emerging art market.

Even if certain painters were assured a certain respect from their patrons, they were not allowed to put their signatures under a work. This is one of the reasons why the attribution of Renaissance paintings is so difficult.

If the determining geometric elements of the painting's main content are selected - i.e. those of the arm, head and hand - one cannot help but notice that they are reminiscent of letters.

- The coordinate system from III now appears as two "L", once in normal representation and next to it as a mirrored "L". Leonardo wrote in mirror writing.

- The triangle of the forehead in this context is reminiscent of the shape of a "D".

- the formation of thumb and index finger can be seen as a "V". The V-shaped angle between thumb and forefinger is 18° (green lines) and has its origin in the vertical of the cross.

If you put these letters together, you get L D V, which are Leonardo da Vinci's initials. All three letters are connected by the golden section and a 30° angle (light grey lines).

Conclusion on the geometric analysis

It could be shown that Leonardo da Vinci makes use of a geometric plane that defines what is not recognisable at first glance, but is already guessed at by many viewers. An essential feature of Leonardo's style is the elegant combination of the symbolic angles and proportions of classical Euclidean geometry with the actual subject matter of the painting, in this case the story of John the Baptist.

To emphasise the superiority of painting over other arts, Leonardo uses a John the Baptist preaching by means of geometry. He hints at his beheading in painting, but only performs it geometrically, presumably for aesthetic and idealistic reasons. And he even succeeds in eliciting a childlike gesture from John via geometry by bringing together his mouth and the crook of his arm. So it seems only logical that da Vinci signs his work using geometric shapes that show Leonardo's initials.

More interesting, however, is what Leonardo does not show. He makes no reference to the one central act of the Baptist, namely the baptism of Jesus Christ. Almost as if the contemplation of the viewer is the baptism itself.

History of the painting

The attribution to Leonardo da Vinci is considered indisputable. Moreover, the work is considered the last painting designed by Leonardo.

Leonardo in the service of the Medici

The portrait was probably painted from 1513 onwards, when Leonardo was at the papal court in Rome, six years before Leonardo's death. Pope Leo X at that time came from the famous Medici family in Florence.

Lorenzo the Magnificent

The Pope's father, Lorenzo the Magnificent, was known in Florence as a great patron of the arts. Among other things, he was a patron of Leonardo's teacher Andrea del Verroccchio, whom he provided with a number of commissions. Certainly Leonardo himself was also involved in the commissions. Lorenzo also supported another famous member of the Verrocchio workshop, Leonardo's seven-year older classmate Sandro Botticelli.

In addition, Leonardo's father, a well-known Florentine notary, worked several times for the Medici. Leonardo's time in Florence is therefore closely connected with the Medici family.

Giuliano di Lorenzo de' Medici

Lorenzo's sons continued his tradition of patronage. It was also the Pope's brother Giuliano di Lorenzo de' Medici who invited Leonardo to Rome in 1513, after Botticelli, Michelangelo and Raphael had already followed the papal call to Rome in the past.

Due to the close connection of the Medici family with Florence, the religiousness that goes hand in hand with the papacy and the importance of John the Baptist as the patron saint of Florence, it is very likely that the painting was commissioned by or under the influence of the Medici in Rome.

The eyewitness account of de' Beatis

When Leonardo da Vinci was summoned to the court of the French king in 1516, the painting was seen there by Cardinal Luigi of Aragon, who visited Leonardo in October 1517. His scribe Antonio de Beatis recorded the following:

"In one of the precincts my lord and the rest of us went to see the Florentine Leonardo Vinci [...] who showed his illustrious lordship three paintings: one of a certain Florentine woman, a very beautiful painting made at the request of the Magnifico Giuliano de Medici, the other of a young John the Baptist, and one of the Madonna and her son being placed in the lap of Saint Anne, all very perfect."

There is little doubt today that the young John the Baptist mentioned by de Beatis is the painting on display in the Louvre.

At the court of the French king

That the painting was known at the court of the French King Francis I is shown by a 1518 portrait of the king as John the Baptist by the later court painter Jean Clouet.

The work is very probably inspired by Leonardo's depiction. This is indicated by

- the position of the cross staff and the king's head tilted slightly to the left

- the prominent prominence of the index finger by touching the forehead of the lamb. The lamb here is symbolic of the opera lamb of God, i.e. Jesus Christ. It is very unusual to place the index finger on the forehead of the lamb and probably only serves to set the scene for the index finger of the Baptist, as is also characteristic of Leonardo's painting

- According to tradition, the skin of the Baptist should be a camel skin. The spotted coat, however, which can be seen in this painting as well as in Leonardo's, does not come from a camel.

It is not known today why Francis I had himself portrayed in this style. It could have been a painting competition between Jean Clouet and Leonardo or a political statement by the monarch.

Unclear whereabouts until 1630

How and when the painting came into the possession of the French kings can no longer be traced today. This is due, on the one hand, to the poor state of the sources in general and the inadequate documentation of the royal collection in particular.

On the other hand, a large number of more or less good copies make exact attribution difficult. There are some written sources in which the owners of a John the Baptist depiction describe a painting in the style of Leonardo's work, but they could also have possessed a copy and supposedly assumed that it was the original. Such sources therefore hardly allow any clear conclusions to be drawn about the whereabouts of the painting.

In the absence of a consistently conclusive explanation of ownership, it is now widely assumed that the painting was part of the French royal collection until 1630.

In the possession of the English crown

There is no doubt that the painting came to England in the 1630s from the possession of the French king. This is adequately documented by an entry in an inventory list of the collection of the English King Charles I drawn up in 1639.

The entry shows that the French King Louis XIII sent a diplomatic mission to England in 1630 to congratulate the English King Charles I on the birth of the heir to the throne, Charles II. The envoy was led by Roger du Plessis, Duke of Liancourt, who carried the painting of John the Baptist with him. He then exchanged it with the English king for a portrait of Erasmus by Holbein and a Madonna by Titian.

These paintings subsequently remained in the possession of the Duke of Liancourt, which gives rise to the assumption for some that he himself was the owner of the painting of John the Baptist, especially as he was known to be a great art collector. Another explanation could simply have been a generous reward from the French king for successful diplomatic service.

Charles I came into conflict with the English Parliament and was beheaded in 1649 after losing a civil war. It was the first execution of a reigning monarch in Europe.

Like the Queen for her portrait, the King has taken off his crown

Henrietta Maria was Queen of England from 1625-1649. She was the daughter of the French Queen Maria de' Medici.

The painter Anthonis van Dyck was a close collaborator of Rubens, who was personally closely associated with Maria de' Medici. Van Dyck was court painter to the English royal family from 1632 until his death in 1641.

Back in France

After the death of Charles I, several dozen paintings from the king's collection were bought by the German banker and art collector Everhard Jabach in 1651. However, Jabach ran into financial difficulties a few years later and had to sell a large part of his collection to the French King Louis XIV (Sun King) between 1661 and 1662, including the portrait of John the Baptist. The painting then remained in the French royal collection.

In 1789, the French Revolution occurred, as a result of which the French King Louis XVI was first deprived of his power and finally publicly beheaded by guillotine in 1793. It was the second execution of a reigning monarch in Europe.

The king has taken off his crown for the portrait. He rests his left hand on a staff supported by an empty chair. In the background falling blue fabric. The king looks forward joyfully.

The downturned corners of the mouth and the upturned lower lip are a characteristic feature of Leonardo da Vinci's profile drawings. Surely David, who later became Napoleon's court painter, thought when he saw Marie-Antoinette how forebodingly auspicious Leonardo's painting of St John must have seemed to the royal owners

The royal collection was dissolved after the death of the French king in 1793 and became the property of the French state. Leonardo da Vinci's John the Baptist has been on public display at the Louvre since 1801.

The painting is now in Room 710 in the Louvre's Grande Galerie.

Significance for art history

The painting achieved great fame and notoriety shortly after its creation, especially through the numerous copies. The aesthetics of the strong light-dark contrast deeply impressed many subsequent painters. Caravaggio and Rembrandt probably serve as the most prominent examples here.

But the special depiction of the body turned in on itself was also considered perfect in form and remains exemplary to this day. Leonardo tried to achieve the ideal dynamisation of a body by twisting it. In doing so, he plays with the perfect rendering of light and shadow, which support the dynamics of the movement, and ultimately build up the volume that gives the figure its liveliness.

The painting represents the culmination of the painting technique called sfumato, which Leonardo da Vinci developed. This involves applying countless fine layers of oil paint so that the lines and brushstrokes are fully resolved.

The extraordinary thing about Leonardo's work is that he succeeds in depicting the drama of the figure using the most economical means. It is an absolute reduction to what is necessary. Leonardo refrains from using landscape, architecture, people, animals or colourful garments. He uses only fine nuances of only two shades of colour.

Nevertheless, he succeeds masterfully in transferring John's fate into the viewer's perception. It shows once again how Leonardo's views on the science of painting merge with the level of the actual representation of the subject of the painting. For this reduction to the necessary is precisely not a mania on the part of the painter, it is a stylistic device to depict John the Baptist, known for his austere lifestyle, most aptly. The elegance of the transition between these levels is what makes Leonardo's works so unique.

Reference to Raphael's last painting

Raphael (1483-1520) is considered the most important artist of the Renaissance alongside Michelangelo and Leonardo. Leonardo's influence on Raphael is undisputed and decisive. His most important works are consistently associated with Leonardo. Raphael died in Rome in 1520, a year after Leonardo's death, aged only 37. He was there supervising the construction of St Peter's Basilica, which his predecessor Bramante had designed and begun. Bramante worked closely with Leonardo and was strongly influenced by Leonardo's architecture.

Raphael's last painting, the Transfiguration, was painted during this period. The painting blends several scenes from the New Testament into one, including the healing of a moonstruck boy (Mt 17:14). Until the beginning of the 20th century, the painting was considered the most famous painting in the world. It was only when the Mona Lisa suddenly became very famous as a result of the famous theft of 1911 and subsequently gained more and more fame that Raphael's last painting increasingly lost its significance.

It is significant for Raphael's engagement with Leonardo that his last work also has clear references to Leonardo's paintings. This is particularly evident in the posture of the persons depicted.

For almost 400 years, this painting was considered the most famous painting in the world.

The moonstruck boy is depicted with squinting eyes. In a twisting movement he points upwards with one index finger. In the context of the painting, the manner of depiction undoubtedly refers to Leonardo's likewise cross-eyed John the Baptist.

The painting was created at the time of Raphael's birth. The angel points to the boy John the Baptist

The lady in the foreground assumes the same posture as the angel in Leonardo's Virgin of the Rocks

Like Leonardo's John the Baptist, the painting is characterised by a novel, very dynamic-looking rotational movement

The unusual posture and the elaborately wrapped robe of this person are strikingly reminiscent of the posture of Mary in Leonardo's Anna Selbritt.

At around 9m wide, this huge painting is Leonardo's magnum opus and focuses on Jesus Christ.

In Raphael's last painting, Jesus Christ is also at the centre of the depiction. In view of the many references to Leonardo's paintings, it is only a detail that the disciple at the left edge of the picture assumes the same hand posture as Leonardo's Jesus: the arms stretched out into a triangle, the left hand open upwards, the right open downwards, the index finger pointing meaningfully downwards

Raphael knew Leonardo personally, admired him and often imitated his paintings. The fact that, regardless of Raphael's early death, his most important work, the Transfiguration, refers to the only of Leonardo's undoubtedly genuine paintings that have a religious content (Madonna of the Rocks, Last Supper, Anne the Third, John the Baptist) is one of the mysteries for which Renaissance painting is still famous today.

According to this, Raphael did not quote three of Leonardo's undoubtedly genuine paintings in his Transfiguration. It is precisely the paintings that have no religious background.

The painting is one of the seven undoubtedly genuine paintings by Leonardo. No allusion to the painting can be found in Raphael's Transfiguration

This painting is also one of Leonardo's seven undoubtedly genuine paintings. It is also not quoted in Raphael's Transfiguration.

An undoubtedly genuine painting by Leonardo. The Mona Lisa is also not quoted in Raphael's Transfiguration

His death caused the greatest sadness to all who had known him. Never had painting been more honoured by an artist.

Downloads

Sources

Website of the exhibiting museum: Louvre-Museum, Paris

Frank Zöllner, Leonardo, Taschen (2019)

Martin Kemp, Leonardo, C.H. Beck (2008)

Charles Niccholl, Leonardo da Vinci: Die Biographie, Fischer (2019)

Johannes Itten, Bildanalysen, Ravensburger (1988)

Die Bibel, Einheitsübersetzung, Altes und Neues Testament, Pattloch Verlag (1992)

Highly recommended

Marianne Schneider, Das große Leonardo Buch – Sein Leben und Werk in Zeugnissen, Selbstzeugnissen und Dokumenten, Schirmer/ Mosel (2019)

Leonardo da Vinci, Schriften zur Malerei und sämtliche Gemälde, Schirmer/ Mosel (2011)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/b/csm_leonardo-alle-gemaelde_2dc4b01ef6.webp.pagespeed.ce.ohfmgl8OfF.webp)