Virgin of the Rocks

The Virgin of the Rocks is the first independent and completed painting by Leonardo da Vinci. It is dated 1483-1486 and depicts Mary, the mother of Jesus and an angel, and Jesus and John the Baptist as boys. The original painting is now in the Louvre in Paris. The commissioning monks were dissatisfied with the depiction. A 20-year legal dispute ensued, so that a second, slightly altered version had to be made by Leonardo's workshop. This is in the National Gallery in London.

Urged on by my longing desire and longing to see the great abundance of the manifold and strange forms which artful nature produces, I arrived, after having wandered for some time among the dark rocks, at the entrance of a large cave. I stopped in front of it for a while, duly marveling and not knowing anything about it, then I bent my back, resting my left hand on my knee and with my right I shaded my lowered and furrowed eyebrows. I bent here and there to see if anything was visible inside. But this remained to me because of the big darkness which ruled there inside. After I had remained like this for a while, two feelings arose in me: Fear and desire: Fear of the threatening dark cave and the desire to explore whether something wonderful was hidden in it.

The London version is shown on the back (third button from the right)

Virgin of the Rocks (1st Version, Louvre)

Leonardo da Vinci1483-1486

Oil on wood, 199 × 122 cm

Musée du Louvre, Paris (inventory number: 777)

Virgin of the Rocks (2nd Version, London)

Workshop Leonardo da Vinci

1491-1508

Oil on wood, 189.5 × 120 cm

National Gallery, London (exhibition room 66)

Biblical background

The painting was conceived as an altarpiece and refers to the Protoevangelium of James, an extrabiblical legend according to which Jesus Christ and John the Baptist may have met in infancy.

The persons depicted

The four persons are biblical characters that corresponded to the imagination of the commissioning monks. The representation of a Mary and Jesus was contractually specified by the monks, as well as several angels and two prophets. Leonardo, however, deviated from the specifications in the execution and determined the figures according to his own ideas.

Mary, mother of Jesus

She is the mother of Jesus and became pregnant through the miracle of the immaculate conception.

- The patrons of the painting were Franciscan monks of the Order of the Immaculate Conception and thus followers of the cult of Mary

Jesus

Son of God and Savior of mankind, performed numerous miracles and was executed on the cross for allegedly deceiving the people. After he died, there was the miracle of his resurrection

- The painting was to serve as an altarpiece of a Christian chapel, the depiction of Jesus was prescribed by the monks

John the Baptist

His mother, the elderly Elisabet and the young Mary were relatives. They miraculously became pregnant six months apart (lk 1:36). John was exactly six months older than Jesus. John's Day (John's birth) is celebrated today on 6/24, six months before 12/24 (Christmas/Christ's birth). John the Baptist preached as a prophet of the soon coming of God and baptized Jesus and others. He was later arrested as a rebel and executed by beheading.

- John the Baptist is the patron of Florence, Leonardo's hometown

- At the same time, John was the patron of the Order of the Immaculate Conception, the commissioner of the painting

An angel

It is unclear which angel is shown. In connection with John the Baptist, Uriel is often mentioned, the fourth archangel and angel of light. But it could also be Gabriel, the angel of the Annunciation, who predicted the miraculous pregnancy of John's mother Elizabeth, as well as Mary and was henceforth considered their protector.

What scene is it?

Leonardo was free to choose the scene. He chose a narrative that allowed him to depict the greatest possible variety of interesting elements of nature. He chose the flight from Egypt.

Escape of the Holy Family to Egypt

The New Testament tells us that shortly after Jesus was born, there were prophecies that spoke of a new king of the Jews (Mt 1:1). The reigning king Herod felt threatened and had all male children up to the age of two killed in his kingdom (infanticide of Bethlehem).

Mary then fled to Egypt with Jesus and her husband Joseph. The flight and especially the rest on the flight have always been a popular motif in painting.

Flight of Elizabeth and John

In the extra-biblical Apocrypha (Protoevangelium of James) it is told that at the time of the infanticide Elizabeth fled to the mountains with her child John. When she found no shelter there, "the mountain split and received her. And that mountain let a light shine through for them. For an angel of the Lord was with them and protected them".

Did John and Jesus meet in a cave?

The cave is associated in the protoevangelium of James only with the flight of Elizabeth and John, but not with that of Mary and Jesus. Moreover, the Protoevangelium of James is not canonical and differs in numerous details from the New Testament. James predominantly tells the prehistory of Mary and her mother Anna and ends at the time of the birth of Jesus Christ. Therefore, the book is popular mainly in the devotion to Mary.

A meeting of John and Jesus during the flight can be assumed because of the kinship of Mary and Elizabeth, but is not told there. The meeting of the two families in a cave is therefore a pictorial invention of Leonardo and the only representation of this kind.

For the painting of importance is the fact that in James version Mary does not give birth to Jesus in a stable, but in a cave. Thus, in this extra-biblical narrative, the painting's titular cave has an elemental significance for both Jesus (birth) and John (place of refuge).

The Madonna is surrounded by a dark forest and rocks. Fra Filippo Lippi was one of the teachers of Leonardo's fellow student Botticelli

Mantegna's work unusually shows the Madonna in a cave. Mantegna stayed frequently in Florence

Symbolism

Leonardo's painting is most famous for the fact that the assignment of the persons is not clear. Against the background of the vague information about the lives of the biblical characters, Leonardo succeeds in a fascinating game with the common ideas. However, this interchangeability of the depicted persons led to a legal dispute between Leonardo and the commissioning monks, as a result of which a second version had to be made. This was slightly changed so that Jesus and John could no longer be interchanged. So the John got, among other things, a John's staff.

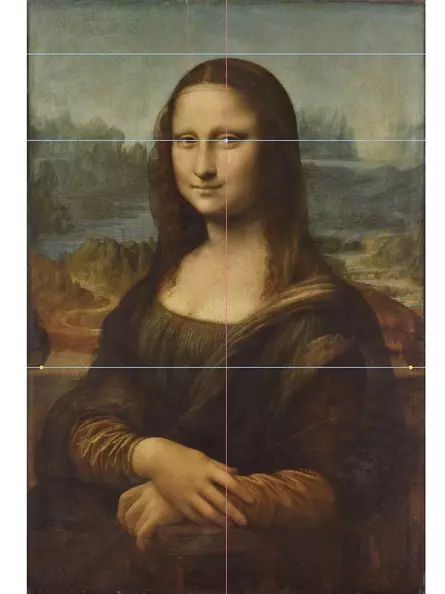

John or Jesus?

Already the contemporaries noticed that it is difficult to tell who is Jesus, and who is John. Basically, John is depicted on the left and Jesus blessing on the right.

What Leonardo does differently

Leonardo deliberately omits any characterizing attributes, so John does not wear a coat of camel's hair, nor does he hold the long staff of John.

Leonardo's depiction deviates from the iconography. He shows a transparent and therefore hardly recognizable cloak of the young Baptist

Here the kneeling boy John wears the typical apron and the long staff of John

1615,

Rubens dispensed with the staff, but the cloak is recognizable as a camel skin, which according to tradition John the Baptist wore

The depiction also otherwise contradicts the common symbolism of Christian painting.

- John is depicted elevated above Jesus

- John is partially covered by the mantle of Mary, the young Jesus sits threateningly close to a precipice

- John is closer to Mary, so that he can be touched by her, the young Jesus is further away

- the angel does not point to Jesus, but to John

- John is looked at directly by Mary and Jesus. He is the only one who is looked at by two persons

- This constellation of figures gives the impression that John is the center of the scene.

The surprising change

Knowing this, the infant Jesus (the one below) can be seen as John. His blessing gesture is reminiscent of John baptizing. The upper left child, somewhat elevated as is usual for depictions of Jesus, now as Jesus, accepts John's baptism in a prayerful posture.

If the facial features of both children are observed, there is hardly any difference. Both look without delight and anticipate thereby their cruel fate. John is beheaded, Jesus is crucified.

Leonardo resolves this interplay by placing the left figure spatially at the left edge of the picture, whereby it loses significance, whereas the right child is close to the center of the picture and appears slightly brighter. Furthermore, the kneeling body of the Madonna is directed towards the right child, which makes him gain importance again, until he is once more placed in relation to the other figures, and the interplay begins anew.

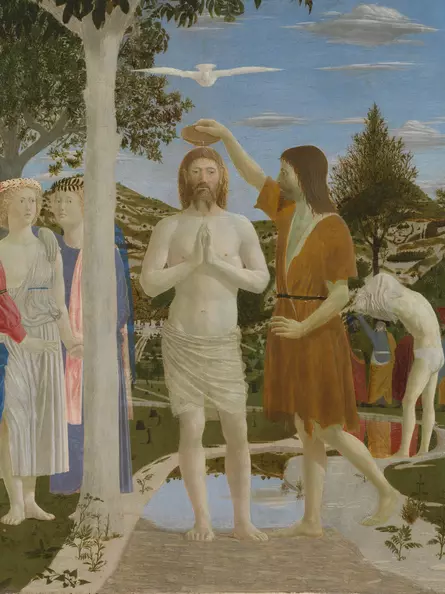

The praying hand position of Christ is exemplary for representations of the baptism of Christ by John the Baptist

The hand position of the Christ is exemplary for this form of representation. Leonardo uses it in the form for the Virgin of the Rocks

The conflict with the monks

The commissioning monks of the Order of the Immaculate Conception tolerated this ambiguity to a certain extent. From the name of the order it can be inferred that they were very attached to Mary, the Mother of God, and John the Baptist was the patron of the order. Therefore, they did not mind if the Madonna and John were more prominently featured.

But the lack of distinction of the boys was a problem for them. So was the angel's finger pointing, which could be misunderstood in a religious context. In the later London version, John was made clearly recognizable by distinct attributes, the angel's finger pointing was removed, and the scene was slightly enlarged so that John was moved even further to the edge and the Jesus figure took on a more central role.

Mary or Elizabet?

The interplay does not only refer to the two children. Likewise, the identity of the two women is not clear. Leonardo was a master at giving figures an androgynous appearance when the pictorial narrative demanded it, but here he has dispensed with this. Therefore, there are two female figures, since the angel on the right does not have male features at all.

Where is John's mother?

Leonardo quotes a story from the Apocrypha. There it is told how John's mother Elisabet hides in a cave with her son. The painting assumes that Mary and Jesus, who are also on the run, met them there. The painting recreates this moment of the meeting of the relatives.

It is absolutely obvious in this context that John's mother Elisabet must be present. She will hardly have given her infant out of her arms. Accordingly, the two female figures would have to be Mary and Elizabeth.

An angel or Elisabet?

The wings of the right angel are barely visible against the rock. The color tones and the shadow of the angel are chosen in such a way that they can easily be overlooked. Even in the better-preserved London version, the wings are barely emphasized. Leonardo thus deliberately wanted the angel to appear more human. A human being who is unmistakably female. In the context of the apocryphal text, it can then only be Elisabet.

Elisabet or Mary?

Analogous to the interplay of the children, the identity of the two mothers can now change. Each can now be Mary or Elizabeth, depending on whether the child she touches is Jesus or John.

That ambiguity was Leonardo's intention is proven by the choice of colors. The monks had it contractually stipulated that the Madonna must be painted with a blue cloak. Blue was the iconographic color for Marian robes. Leonardo deviated from the stipulations here as well, for the woman's cloak in the center is painted predominantly in shades of green, with dark blue only in the darker areas. Only in the London version is the cloak then really blue.

The chronology of Elisabet and Mary

For the painting, the higher position of Elisabet compared to Mary can be justified in the biblical context.

- Elisabet was a woman of advanced age (lk 1,18). So old, in fact, that her husband did not believe she could ever conceive again

- the archangel Gabriel came first to Elisabet's husband and announced to him her miraculous pregnancy

- Mary was the younger one, the archangel Gabriel came to her only when Elisabet was six months pregnant and announced to her the birth of the Messiah

Thus, a chronology can be discerned. If the painting is now viewed from top to bottom as a chronological family tree, it is shown that Elisabet gave birth to John and shortly thereafter Mary gave birth to Jesus. Since the Madonna is without doubt the more important of the two women, however, the central role in the painting comes to her and the interplay dissolves again. That both women are shown in young years, serves here also the possibility of confusion.

The famous finger pointing of the angel

Leonardo takes the ambiguity of the figures in the altarpiece to the extreme when he paints a pointing finger on the angel. Radiological examinations of the painting have shown that this cannot be found on the underdrawing, and it is also missing from the later London version. The pointing finger is often associated with John the Baptist, as Leonardo shows an identical hand position in what is probably his last painting, the image of John the Baptist.

The right hand of the angel

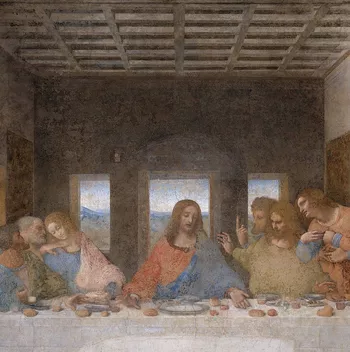

Leonardo's central major work also shows the gesture

The posture of the Baptist's right hand is almost identical to that of the angel of the Madonna of the Rocks.

The Immaculate Conception of Mary

So far, it has been ignored that Leonardo's painting quotes the Protoevangelium of James also with regard to Mary. For in the extra-biblical narrative, Mary does not give birth in a stable, but in a cave. Subsequently, in the narrative, an incident occurs that was the cause of numerous debates in Leonardo's time, especially among the Franciscan friars, the debate about the possibility of immaculate conception.

Salome's finger test

James relates that after Mary gave birth to Jesus in the cave, her nurse met a Salome and told her about a virgin giving birth to a child. Salome strongly doubted the story and insisted on testing Mary's virginity herself:

"As the Lord my God lives, unless I put my finger down and examine her condition, I will not believe that a virgin has given birth. And the midwife went in and said, 'Mary, lie down ready.' For no small strife is rising about you.' And Mary heard it, and lay herself ready. And Salome laid down her finger to examine her condition." (Protoevangelium of James)

After the examination, Salome repented and an angel appeared to her, inviting her to take the child in her arms. She took it up and said, "Homage I will pay to him, for a king has been born to Israel."

The color coding

The angel's red cloak is a striking counterpoint to the skin tones, the gray of the rocks, and the green of the clothes and plants. Leonardo has thus placed a striking red color area on the right side, which contrasts with the contextual meaning of the child on the left (the interplay of the figures of Jesus and John).

Red can have different symbolic meanings depending on the context. In the context of the cave, Mary's presence, and the finger pointing of the figure on the right, the angel in the red robe now appears as the unbelieving Salome of the Jacob narrative, who test(s) Mary's immaculate conception. Her finger now points not to the boy John, but to Mary's womb. Her smile expresses her incredulity, and at the same time her joy at having passed the test.

The red of her cloak now refers to the humanity of Salome and the flowing blood, since she cannot give birth immaculately (A birth is associated with blood loss). Mary, on the other hand, experienced the miracle of immaculate conception, and no red can be found on her. Rather, even after giving birth in the cave, she is still pure as a jewel.

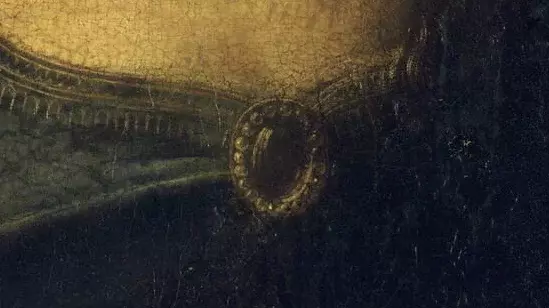

The clear jewel holding Mary's cloak together refers to Mary's immaculate conception

Conclusion on the mutability of the characters

Leonardo thus tells at least two stories in the Madonna of the Rocks. One is the story of Mary's virgin birth in the cave, and the other is the story of the flight of Elisabet and John the Baptist into a cave. Both stories are extra-biblical and taken from the same apocryphal Protoevangelium of James.

This kind of merging of different narratives in one picture is typical of Leonardo paintings. In doing so, he masterfully met the demands placed on him by his patrons. On the one hand, he succeeded in placing the story of John the Baptist and Mary before the story of Jesus, and on the other hand, at the same time, he referred to the question of the Immaculate Conception, which the Franciscans were discussing at the time and after which the commissioning order was named.

The modern way of pictorial narration

Leonardo's first independent and completed painting thus shows his attitude to the question of how pictorial narratives must be composed in a modern way. The revolutionary nature of his work becomes clear when it is compared to the best of his time. Here is a work by Botticelli commissioned by the pope, done at about the same time, which today stands right next to Michelangelo's famous paintings in the Sistine Chapel in Rome.

Botticelli was a former classmate of Leonardo in Verrocchio's workshop (Florence). The painting combines several scenes from Moses' life (Moses is depicted in a green/yellow cloak). Such arrangements were widespread in the Renaissance. Leonardo deliberately broke with this tradition, because it was his ambition to tell many stories in one moment. Because that was only possible for painting, not for music and not for poetry.

The cave

The cave as a place of refuge is taken from the apocryphal text from which Leonardo was inspired. In this text, the mountain splits and offers shelter to Elizabeth and her son John from Herod's child murderers.

The rock

The surrounding rock is thus a symbol of faith in God. It serves as a refuge from the dangers of the world and separates the good of the world from the evil around it. Leonardo does not close the rock upward, but opens it so that, as the apocryphal text says, "light [can] shine through, for an angel of the Lord was with them and protected them."

The light

Light is Leonardo's self-evidently recurring motif and serves as a symbol of the light of God that can illuminate even the deepest darkness. It is associated both with John, who was not himself the light but was to bear witness to the light (joh 1:5-8), and with Jesus, the "light of the world" (joh 8:12). Their naked bright bodies indicate this fact.

The plants

The light is also the reason why plants can grow in the rocky desert. The exact destination of the plants is a subject of continuing debate, but there is much to suggest that the plants were deliberately chosen and, through their symbolism, point to the future destiny of Mary and Jesus.

The Sea

The sea in the left background of the painting is also said to be a reference to Mary. Leonardo had a penchant for puns, so he surrounded the Ginevra de' Benci with a giant juniper (Ital. 'Ginepro'), or he painted the Cecilia Gallerani, with a weasel (altgr. 'galéē'). So also here, because behind the Maria rises the infinite sea (ital. 'Mare'). Leonardo would not have had to show water outside the cave to tell the apocryphal story of the James.

Birth and Resurrection

James states that Jesus did not come into the world in a stable, but in a cave. Thus, the cave is a symbol of the birth of Christ, that is, the incarnation of God (Jesus is called the Son of God).

The final miracle of Jesus is his resurrection. According to the Bible, after he was crucified and died, he was laid out in a cave for three days. Then he rose from the dead and left the cave.

According to James apocryphal legend, the cave is thus a symbol of both the beginning (birth) and the end of the Jesus narrative (laying out and resurrection).

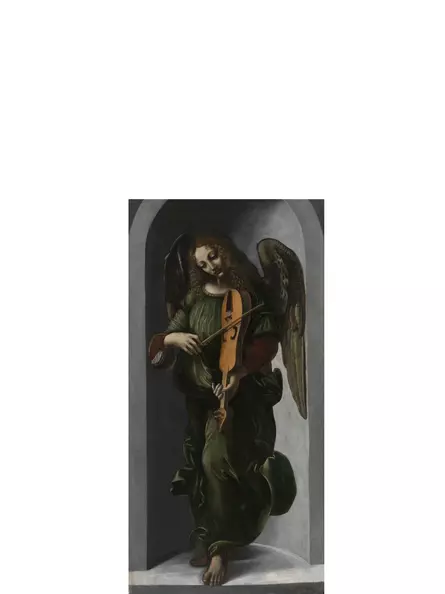

Geometric analysis

When Leonardo took the commission for the Madonna of the Rocks, the altar was already constructed in shell. Leonardo's workshop undertook only the painting of the central panel and the painting to the left and right of it (two angels making music). The framing 18 panels, which were much smaller, were made by other painters. This shows that Leonardo had no leeway with the format. He had to use the space given by the altar construction.

I Golden section

The basic format of the painting was laid out by the architect of the altar in the golden section, likewise the upward closing arch goes back to his design. Leonardo takes up this proportion.

- the height of the painting relates to the width in the golden section. The outer dimensions therefore form a golden rectangle. However, the painting must be shortened somewhat in height for this, so that the proportion of the golden section is actually exactly correct (orange dashed line; comparison original to ideal: 0.6074 vs. 0.6108 = approx. 0.6% deviation)

- the height of the painting is divided in the golden section in such a way that the group of figures is below the upper head end of the Madonna (upper orange line)

- if this height is divided again in the golden section, it now passes through the eyes of the Baptist (blue dot), also the shoulder of the angel is tangent (lower orange line)

- by dividing the golden rectangle format of the painting in the golden section, two squares are created, in each of which a circle can be drawn (white circles). The upper one forms the round arch, the lower one encloses the group of figures, which is especially visible at the foot of the left child (mouseover)

- the upper circle passes exactly through the right eye of the angel (blue dot). This kind of connection of geometry with representation is typical for Leonardo

If a golden rectangle is divided in the golden section (blue horizontal line), a golden rectangle (upper smaller rectangle) and a square (blue lines) are created again. The rectangle can also be rotated

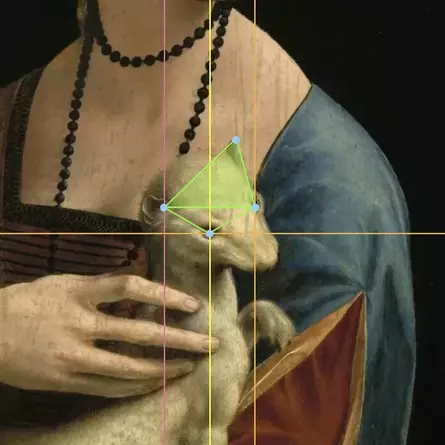

It is typical for Leonardo to combine geometry with representation. The eyes of the ermine are cut by the golden section of the picture width and height respectively

The central perpendicular intersects her left eye. The column feet are in the golden section of the height of the picture, by continuous division upwards the eyes and the head end are also in the golden section.

The inaccuracy of the upper arc

Leonardo has given less care to the upper part of the altarpiece. Thus, the arch that ends at the top is not circular, but of a slightly lower height on the left (upper white circle). This suggests that a certain part of the painting was to be hidden by the framing, namely the upper one.

The London version was eventually given to the monks for the altar. It is about 10cm less high, shows hardly any sky at the top, and with an aspect ratio of 0.613 is closer to the golden ratio (0.618) than the Louvre version (0.607). This and the non-existent details at the top of the image strongly suggest that the upper part of the Louvre version should always remain obscured. The Louvre then also displays the work today in such a way that the part above the orange dashed line is obscured.

The original altar has not survived. It is possible that it was inaccurately made toward the top or unfinished in detail, and that Leonardo deliberately painted the painting slightly higher than was necessary to provide some clearance for the vertical positioning of the painting in the frame.

Direction of the painting composition

Basically, it can be stated that the painting was composed from the bottom up from a geometric point of view. This is evident from the intersections of the golden section in the eye of the Baptist, as well as in the eye of the angel.

- the upper circle can be placed exactly at the upper edge of the picture and then exactly meets the other eye of the angel (mouseover)

Since, from a geometrical point of view, no further relationships result from the composition from top to bottom, the intersection of the circle with the right eye of the angel is surely only a hint by Leonardo to the lack of accuracy of the surrounding frame. Leonardo always attached great importance to geometric harmony.

II Golden spiral

In a golden rectangle, the sides are in the ratio of the golden section to each other. The Virgin of the Rocks was created as a golden rectangle.

By continuous division of a golden rectangle in the golden section, a square and a smaller golden rectangle are created for each division. If a quarter circle is drawn into a square created in this way, a golden spiral is created (lower illustration).

This is an approximate construction common during the Renaissance, the actual logarithmic curve is slightly different.

The Golden Spiral occurs when the radius of a circle is shortened by the factor of the golden section when it is rotated around the center every 90°. Blue and orange lines are in the ratio of the golden section

The left part of the band forms a golden spiral

Diagonals and course of spiral

A special feature of the Golden Spiral is the determination of its center. It is located at the intersection of one diagonal of each of the two outer surrounding golden rectangles (yellow lines). Only these two diagonals are at the same time a diagonal of every other golden rectangle within the divisions.

- the longer of the two diagonals is tangent to the left eye of the Madonna and exactly separates her neck brooch (longer yellow diagonal)

- the shorter of the diagonals can be moved up in parallel so that it intersects both the neck brooch of the Madonna and the right eye of the Baptist (mouseover, dashed line)

- the golden spiral is tangent to the garment and the shoulder of the angel and intersects the hidden right eye of Jesus

If the findings from I are added

- golden intersection of the image height by the left eye of the Baptist (blue dot)

- the circle on the golden section of the picture height cuts the left eye of the angel (mouseover)

it is now clear that the eyes of all four figures are connected by the golden section. On the eyes of the baptist a main emphasis was put with the construction of the golden section, because only with him both eyes are cut.

III Steady halving

Besides the golden section, the painting also shows the principle of continuous bisection.

- the diameter of the upper circle divides the painting into the upper arc and a rectangle below it. Half the height of this rectangle runs exactly along the angel's index finger (red horizontal line, blue dot)

- the central perpendicular is tangent to the left edge of the Madonna's neck brooch

- to the left and right of the central perpendicular the painting can be divided vertically again (white vertical line). The left vertical intersects the left eye of the Baptist, the right vertical intersects the right eye of the angel

- in the third quarter from the left there are again telses. The first one leads to a vertical through the left eye of Jesus, the second one to a vertical through the thumb of the Madonna and the two blessing fingers of Jesus

- due to the symmetry of the white verticals, the upper circle can also be bisected, since it thus rests on both (upper smaller white arc ). This connection becomes important in the following

Due to the constant bisection, there is also a golden section here

- the lower rectangle, which is limited by the upper circle diameter, can be divided in the height again in the golden section and meets also here the left eye of the angel (mousover, orange line)

- the index finger of the angel divides the height of the left eye of the angel and the fingertips of the blessing Jesus in the golden section (mouseover)

- blessing fingers of Jesus and elbows of praying Baptist are on one height

Eyes and hands as geometrical markings

Once again it becomes clear what an important role the eyes play in the composition of the picture. They are not only marking points for the golden section, but also for vertical and horizontal divisions. The two blessing fingers, which are exactly under the left thumb of the Madonna, are to be understood as Leonardo's reference to the principle of the constant division: 1:2(:4 ... etc). It is interesting that Leonardo only now begins to include the hands as well. The four hands of the center of the picture can be connected by only two lines: on the one hand the horizontal line of the index finger of the angel to the praying hands of John, on the other hand the vertical line from the thumb of the Madonna to the blessing fingers of Jesus. The spacing and positioning of these four hands are reminiscent of a cross lying on its side.

The architectural pattern

Overall, a pattern emerges that is reminiscent of an architectural structure, such as a window, an altar, or even the entrance to a cave. Basically, the structure created refers to the fact that architecture has its origin in geometry and expresses the principle, valid until the 20th century, that any design perceived as beautiful consists of the harmonious arrangement of its parts. This is particularly evident in the facades of classical buildings.

The fate of the baptist

The horizontal extension of the angel's index finger (red horizontal) runs directly below the head of John the Baptist and directly above his praying hands. The angel's index finger pointing to him thus refers to the Baptist's dramatic fate. He was imprisoned and eventually beheaded. The beheading of John has always been a popular motif in painting.

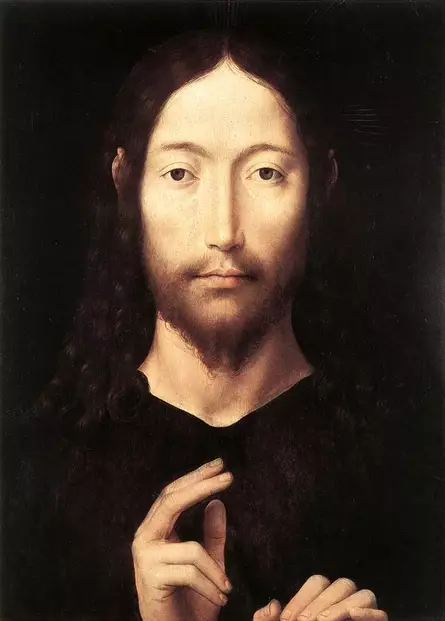

In his last painting, Leonardo also performs a geometric beheading of John. Both paintings are his only depictions of the Baptist.

The vertical and horizontal lines are in the golden ratio of the height and width of the image. A parallel line of their intersection with the index finger runs from the thumb below the head. In this way Leonardo refers to the beheading of the Baptist. The two fingers on the chest recall the blessing of Jesus in the Virgin of the Rocks

The beheading of the Baptist at the request of Herod's daughter Salome is a frequent subject of painting. Here next to her mother Herodias with the head of the Baptist. Salome contemplates his head carefully, while she pulls aside the concealing curtain to reveal what is hidden behind it

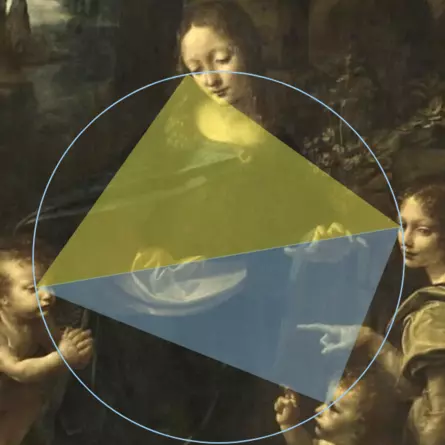

IV Angles and triangles

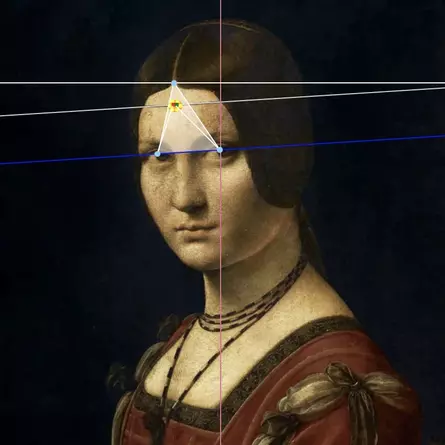

Leonardo has connected the eyes of the persons in the central group of figures via symbolic angles inscribed in a surrounding circle. The eyes of the four persons are the basis for four triangles, which were also created in symbolic angles.

- the eyes of the four persons can be inscribed into a circle which is exactly half the size of the upper circle closing to the top, i.e. it is half the width of the painting (light blue circle)

- the center of the circle is in a vertical line below the left eye of the Madonna. Moreover, it is positioned in such a way that a diameter of the circle intersects the right eye of the Madonna and the central perpendicular of the painting (dashed vertical line). For this purpose the circle was rotated by 6°

- a rotation of the circle by another 3,5° forms a diameter that connects the eyes of the angel and the Baptist (dashed horizontal)

- From the right eye of the Madonna a 36° angle leads to the right eye of the Baptist, from her left eye a 72° angle leads to the left eye of Jesus (orange lines). The 72° angle is the center angle of a regular pentagon (the 36° angle is half, corresponding to the center angle of a regular 10-corner)

- From the eye of the angel a 108° angle spans (mouseover, blue triangle). It points to the eye of Jesus and to the intersection of the circle with the 72° angle view of the Madonna to Jesus (right orange line). The 108° angle (interior angle) is, like the 72° angle (center angle), directly connected to the regular pentagon in geometric symbolism

- The eyes have been placed in the circumcircle in such a way that symbolic triangles can be formed from them (mouseover)

45°,90°, 45° (yellow triangle)

60°,45°,75° (green triangle)

30°,60°,90° (blue triangle)

The apex of the yellow triangle (45°,90°, 45°) deviates by 3.5° from the right eye of the Madonna, but the triangle is too conspicuous to go unmentioned. The principle of superimposed triangles with symbolic angles is also known from other paintings by Leonardo.

Both triangles have their base on the eye line of the Baptist and the angel. The positioning demonstrates the theorem of Thales, after all triangles circumscribed by a semicircle are right-angled

This symbolic triangle was often used by Leonardo. The tip of the angel's finger touches the right side of the triangle exactly

Eyes and ears of the ermine form two triangles. The upper one is the one specifically used by Leonardo (45°,75°,60°). The lower one has the inner angles 30°,120° and 30°.

Eyes and central parting form a special triangle (75°,60° and 45°) tangent to the namesake ferroniere on the left. The eye axis and the browband are tilted exactly 3.5° to the upper right (blue and lower white line).

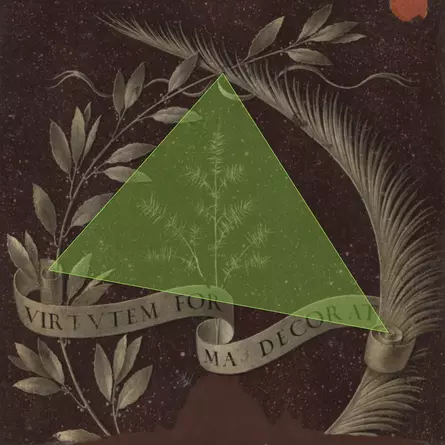

The special triangle (60°,45°,75°) here connects the top of the cluster, as well as the centers of the spirals at the end of the banner.

V Hidden faces

Leonardo recommended looking at a wall to stimulate the imagination: "Likewise, you can see there various battles and figures with vivid gestures, strange faces and garments, and an infinite number of things, which you can then reproduce in perfect form and good shape." (full quote at the bottom of this page). Leonardo has already rendered the figures in the foreground "in perfect and good form," this limitation was important, in his opinion, to distinguish good painters from bad. It is possible that the Madonna of the Rocks emerged from such a meditation.

A surprising parallel

In the background of the picture, Leonardo plays with these deceptions of perception in the shape of the rocks. For the complex geometric system of the center of the picture of eyes and hands is repeated in the form of the rocks and is confirmed by an elementary geometric parallel.

The axis of vision of the Baptist and the angel is inclined 9.5° to the upper right (6° + 3.5°). In the background of the landscape, two rocks appear strikingly in the backlight as shapes that do not seem natural. It is no coincidence that the tops of the two rocks are parallel to the axis of view of the Baptist and the angel, and are also connected by a 9.5° angle. If now the meaning of hands and eyes in the center of the picture is recalled, the two rocks in the backlight can remind of two eyes when seen from a distance, but associated nose and mouth cannot be recognized. It is a conscious irritation of Leonardo, in order to invite looking viewers, "to find out whether inside something is to be recognized" (complete quotation at the beginning of this page).

The baptism

coming soon

The wanderers

coming soon

Melancholia

coming soon

Madonna Rock

coming soon

The Creator

coming soon

The enlightenment of Jesus child

coming soon

History of the painting

To understand why there are two versions of the painting, it is important first to trace the history of the painting, because this explains the differences between the two representations.

The history of the painting is closely connected with the legal dispute shortly after its creation. As a result, there are two versions. The Louvre version is considered the original version for stylistic reasons. The second version, which is in London, is presumably a workshop work, in which Leonardo was only supportive.

Even though numerous documents exist on the creation of the painting, the events of the time cannot be reconstructed with certainty, as the documents show large gaps in time.

The first commission in Milan

Leonardo had left Florence in 1482 and settled in Milan for almost two decades. On April 25, 1483, he signed the contract for his first major commission in the new city. He was to make the central main panel of the altarpiece of the Chapel of the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception. The chapel was part of the church complex of San Francesco Grande. This was the second largest church in Milan after a rebuilding completed shortly before. Milan itself was one of the six largest cities in Europe and was already a metropolis at that time. The commission therefore had a high prestige value.

The monks conceived the altar as a monument of confession to the Immaculate Conception of Mary. The order was named after her. The commission also included two side panels, which Leonardo delegated to two local painters, the brothers Ambrogio and Evangelista de Predis. In addition, gilding work was to be done on the altar. The commission was remunerated at an average of 200 ducats, to be paid in monthly installments over a period of 20 months. A clause allowed for additional payment at a later date should the costs turn out to be higher. However, the amount was at the discretion of the client.

Start of the legal dispute

From the point of view of Leonardo's workshop, the contract was completed after about two years (1486 at the latest), but a dispute arose with the monks, who wanted to pay less in arrears than was demanded. They offered 25, Leonardo's workshop demanded 100 ducats. Leonardo's main panel was therefore not delivered.

A petition from Leonardo to the Duke of Milan is known, dated 1491-1493, already 8 years after the beginning of the commission. In it he complains about the demands of the monks, who "talk about the color like blind men" and demands an independent expert opinion on the value of the painting or else that the work be left to him should the monks continue to refuse to pay the price demanded. For he had already found a buyer for the painting. Researchers agree that this first version is the one from the Louvre, citing stylistic reasons.

End of the dispute

As a result of the dispute, a second version was made, exactly when is unknown. This second painting, together with the side wings of the Predis brothers, was presented to the monks in 1506, and the monks criticized it again, setting a deadline of two years. Only in 1508, 25 years after the beginning of the commission, the second version was handed over to the monks and placed in the altar. The entire altar included 18 other, much smaller panels that were placed around Leonardo's contribution, but were by other painters. The largest of these measured about 1/3 the height of the Predis brothers' music-making angels. Leonardo's painting was the main central work.

The side panels were cut at the top when they were later removed from the altar. Originally, the arch terminating at the top was completely

The version differs from the Louvre version in details and shows less of Leonardo's typical sfumato

Evangelista de Predis did not live to see the end of the commission. He died already in 1503. Possibly his brother Giovanni Ambrogio is the author of this angel.

The London version

This version was in the chapel of the monks in the church of San Francesco Grande until the chapel was demolished around 1576. After that the painting remained in the possession of the Order of the Immaculate Conception. In 1785 the work was sold to an English art collector and from then on it was traded several times in England. The last private owner was Sir Henry Charles Howard, 18th Earl of Suffolk, 11th Earl of Berkshire. He sold the painting to the National Gallery in London in 1880. The side wings made by the Predis brothers also came into their possession in 1898.

The National Gallery in London exhibits the painting year-round in Room 66.

The version in the Louvre

What happened to the first version of the Madonna of the Rocks after its completion is unclear. It is likely, but not certain, that the painting became the property of the Duke of Milan. The Codex Magliabechiano, which many consider to be the manuscript of the famous Leonardo biographer Vasari, writes:

"He [Leonardo] painted an altarpiece for Ludovico, the ruler of Milan, and all who have seen the picture declare it to be one of the most beautiful and unusual works to be found in painting. It was sent by said duke to the emperor in Germany".

It is assumed that this altarpiece refers to the Madonna of the Rocks, because Leonardo is not known to have worked on any other altarpiece in Milan.

Wedding gift for the German king

Duke Ludovica Sforza of Milan, Leonardo's longtime employer, had become ruler of Milan under dubious circumstances and wanted to legitimize his title by marrying the German royal family. Although the Duchy of Milan was de facto independent, it had officially been a fief of the German Empire for centuries.

The duke bought the improper marriage of his niece to the cash-strapped German king Maximilian I and was legitimized as Duke of Milan. According to the above quoted statement in the Codex Magliabechiano, the Virgin of the Rocks could have been a dowry on the occasion of the royal wedding. In 1494 Bianca Maria Sforza married the German king, who was also German emperor from 1508-1519.

Wedding gift for the French king

Emperor Maximilian I came from the House of Habsburg. It is assumed that the painting then came to France as a dowry for weddings of women from the House of Habsburg. The marriage of the French King Francis I to Eleanor of Austria (1530) comes into question. But also that of the French king Charles IX with Elizabeth of Austria (1570). Whereby that of Francis I is the most probable, since he also otherwise acquired all Leonardo paintings, which are today in the Louvre. He was Leonardo's last employer from 1516-1519 and a great admirer of his art.

Other explanations

Except for the entry in the Codex Magliabechiano, there is no evidence to support the theory of Ludovico Sforza's wedding gift. Other approaches are that the painting always remained in Milan and was either bought or confiscated there by the French royal family when they occupied Milan in 1499-1512. It could also have come back into the possession of Leonardo, who worked for the French governor of Milan from 1508-1512. But again, there is no evidence of this.

In France

The Louvre version is first attested in 1625 in the royal collections at Fontainebleau Castle. The collection was moved to the Palace of Versailles by Louis XIV around 1682. During the French Revolution, it was finally transferred to the Louvre, where it has been on public display ever since. In 1806, the painting was carefully detached from the original wooden panel by a restorer and transferred to canvas. In 2011, both versions of the Madonna of the Rocks were exhibited side by side at London's National Gallery of Art.

The Madonna of the Rocks is now in Room 710 in the Grande Galerie of the Louvre.

Significance for the history of art

The Madonna of the Rocks was a revolutionary work in every respect.

Previously unheard of quality of representation

The representation of the scenery placed the highest value on naturalistic depiction of light, water, rock and plants, as well as the human being. Such a quality had never been achieved before. Leonardo's first independent work quickly became famous and was copied in rapid succession by other painters, although the quality of Leonardo was not achieved.

Abandonment of biblical iconography

Leonardo's Madonna of the Cave of the Rocks is also the first work to take an actually religious scene away from this level of meaning and to bring the significance of the figures into a new modernity. The characters, taken by themselves, no longer have a biblical reference. Instead of the Madonna, Jesus and John, it could be any family scene, since typical iconography such as halos or staffs and crosses have been omitted. Nevertheless, Leonardo establishes a biblical reference through subtle symbolism, so that the work had to be understood by his contemporaries as Madonna with Jesus and John, as well as an angel.

The wings of the angel

Leonardo knew from his observations of bird flight and constant reflections on flying machines that the angel's wings were far too small and therefore not very capable of flight. At the same time, Leonardo had been the artistic assistant of his teacher Verrocchios, responsible for the design and thus also the costuming of courtly festivities. Leonardo's great talent for particularly fantastic costumes is still remembered. For example, the wings of an angel in a Leonardo painting should be seen much more as a humanizing costume than as a religious reference. Leonardo is known for his natural philosophy.

This is then what the fantastic angel seems to point out by looking directly at viewers. Leonardo's painting is about creating something for eternity by showing truths that are seemingly eternal. And what can be more eternal than the image of a sheltering woman with two children in front of elements of eternal nature. A nature that is reduced to the most essential: rocks, waters and plants outgrowing it. This very nature-oriented perspective on painting anticipated later developments.

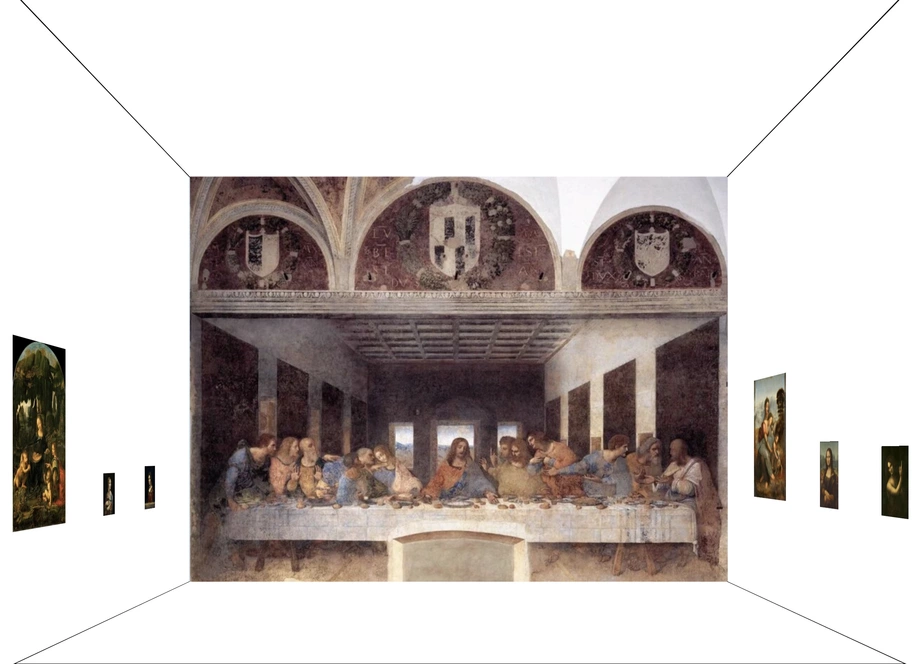

Beginning and end

Leonardo was about 30 years old when he began work on the Madonna of the Rocks. It was Leonardo's first independent and completed work. The depiction of John the Baptist (from 1513) is considered his last work. This connection of the two paintings indicates a cycle of paintings. The Madonna of the Rocks shows John shortly after his birth, at the beginning of his ministry, and Leonardo's last work shows the mystical transfiguration of the Baptist shortly before his cruel end. This nourishes the assumption that Leonardo connected all of his seven undoubtedly genuine paintings through a common narrative. It cannot be overlooked that his entire oeuvre reveals a purely formal systematic: on the one hand chronologically and on the other with regard to the picture sizes.

Outlook

Besides The Last Supper, Leonardo's central major work, only one other group painting is considered a true independent work by Leonardo. The figures of Anna Selbritt are often recognized as Anna, Mary, Jesus and the Passion Lamb. But even there, it becomes apparent to unprejudiced viewers that Leonardo wanted to create something timeless, free from the cultural influences of religion, which are perceived as temporary. For here, too, any clearly characterizing biblical symbolism is missing.

Analogous to the Madonna of the Rocks, the depiction dispenses with any iconography and thus acquires a timeless character. Likewise, rock, water, and plants are prominently depicted. However, instead of the wings of an angel, a lamb is shown here. Anna has almost masculine features and is strikingly larger and stronger than Mary

The early design for Anna Selbdritt dispenses with iconography. Here, too, Anna appears conspicuously masculine

He is not universal who does not love all things belonging to painting in the same way. For example, one does not like the landscapes, he thinks that they are an object to be explored in a short time and with ease. As our Botticelli said, it is in vain to make an effort, because all one has to do is throw a sponge soaked in different colors on the wall, and it will leave a spot where one can see a beautiful landscape.

It is true that in such a spot one can see various fantastic formations of what one wants to look for in it, that is, human heads, various animals, battles, cliffs, seas, clouds, forests and other similar things. And it happens as with the sound of bells, from which you can hear what you like.

But even though these spots may stimulate your imagination, they do not teach you in any way how to work out a detail. And the mentioned painter made very poor landscapes.

Among these rules, however, a new invention should not be missing in the superior contemplation, which, even if it seems poor and almost ridiculous, is nevertheless of the greatest use to stimulate the mind to manifold inventions.

And this happens when you look at many a masonry with different stains or with a mixture of different kinds of stones. If you just think of a landscape, you can see there pictures of different landscapes with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, large plains, valleys and hills of different kinds. Likewise, you can see there various battles and figures with vivid gestures, strange faces and garments, and an infinite number of things, which you can then reproduce in perfect form and good shape.

With such masonry and stone mixture it goes like with the church bells, you find in their striking every name and every word which you imagine.

Sources

Website of the exhibiting museum: Louvre-Museum, Paris

Frank Zöllner, Leonardo, Taschen (2019)

Martin Kemp, Leonardo, C.H. Beck (2008)

Charles Niccholl, Leonardo da Vinci: Die Biographie, Fischer (2019)

Johannes Itten, Bildanalysen, Ravensburger (1988)

Die Bibel, Einheitsübersetzung, Altes und Neues Testament, Pattloch Verlag (1992)

Especially recommended

Marianne Schneider, Das große Leonardo Buch – Sein Leben und Werk in Zeugnissen, Selbstzeugnissen und Dokumenten, Schirmer/ Mosel (2019)

Leonardo da Vinci, Schriften zur Malerei und sämtliche Gemälde, Schirmer/ Mosel (2011)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/b/csm_leonardo-alle-gemaelde_2dc4b01ef6.webp.pagespeed.ce.ohfmgl8OfF.webp)