La Belle Ferronière

La Belle Ferronière is a painting by Leonardo da Vinci, painted in Milan between 1490 and 1499. La Belle (French for "the beautiful one") wears a ferronière, a narrow headband with a jewel attached to it, worn centrally on the forehead. The identity of La Belle is unclear, but the majority of art historians believe it to be a portrait of the Milanese court lady Lucrezia Crivelli. The portrait is now in the Louvre in Paris.

What is beautiful and mortal passes away and has no duration.

Leonardo da Vinci's paintings cannot be understood without examining the geometry of the picture

Leonardo da Vinci

around 1490

Oil on wood (walnut)

45 x 63cm

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Who was the Belle Ferroniere?

The source situation to the painting is very vague, and thus the identity of the young woman is considered until today as unsettled. In the Leonardo research two, mutually exclusive, theories are discussed. Some say that the painting was created between 1490 and 1499 and shows a lady of the Milanese court. This view is held by the Louvre, among others. The others consider it to be a work from the last years of Leonardo's life, when he was at the French court in Amboise (1516-1519). In this case, it is supposed to show a mistress of the French king.

Theory I - A lady from Milan

The majority of those who place the painting in Leonardo's Milanese period consider it to be the portrait of Lucrezia Crivelli, as do the art historians of the Louvre. In addition, it is discussed whether the painting could possibly represent another personality of the Milanese court. The following ladies come into question.

Lucrezia Crivelli

This theory on the identity of the Belle Ferroniere is the most recognized today, and is mainly held by the art historians of the Louvre. Lucrezia Crivelli's life is known only in broad outline. Many of the dates of her life are unknown.

Lucrezia came to the Milan court as lady-in-waiting to the sixteen-year-old Beatrice d' Este, when the influential noblewoman married the Milanese duke Ludovico Sforza in 1491. Ludovico kept a mistress, Cecilia Gallerani, at the time. During this time, Cecilia was portrayed as the 'Lady with the Ermine' by Leonardo. Four months after the duke's marriage to Beatrice, his mistress bore him a son, Cesare Sforza (b. 1491). Thereafter, Cecilia was banished from the Milanese court, lavishly endowed and propertied, and married to a noble retainer of Ludovico.

The power-conscious duke's marriage to the educated and cultured Beatrice d'Este was considered unhappy, and so the duke made her lady-in-waiting Lucrezia Crivelli his mistress around 1495. His wife tried to persuade the duke to banish Lucrezia as well, but the duke refused.

The Duchess Beatrice d'Este bore Ludovico Sforza two sons and died tragically in January 1497 giving birth to the third child, as did her newborn. Beatrice lived to be only 22 years old.

The duke gave himself in great mourning for political reasons. However, Lucrezia bore him a common son, Giovanni Paolo I Sforza, only two months after Beatrice's death. The illegitimate son was later legitimized and became the first Marquis of Caravaggio. Ludovico Sforza was expelled from Milan by the French in 1499 and stripped of his power. Historians at the Louvre have found that Lucrezia was again pregnant by the duke at this time. The duke was able to briefly recapture Milan in the spring of 1500, but was betrayed and died in French captivity in 1508.

Lucrezia Crivelli probably lived at Rocca di Canneto in Mantua from 1500 under the protection of Beatrice's older sister, Isabella d'Este.

Leonardo may have portrayed another mistress of the Duke in Lucrezia Crivelli, as he had previously done with Cecilia Gallerani (the 'Lady with the Ermine'). A poem by Antonio Tebaldeo, in which he praises a painting that Leonardo da Vinci is said to have done of a Lucrezia, is often used to support the thesis. It can be read at the bottom of this page. Tebaldeo was the tutor of Isabella d'Este, Duchess of Mantua and the sister-in-law of the Duke of Milan. He was thus certainly informed of news from Milan, including that Leonardo was making a portrait of Lucrezia Crivelli.

Beatrice d'Este

She was the wife of Ludovico Sforza, who died young, mother of two of his sons, and Duchess of Milan. She was also the younger sister of the influential Duchess of Mantua, Isabella d'Este.

It is reasonable to assume that the Duke of Milan commissioned a portrait of his wife from Leonardo. However, the marriage was considered unhappy:

- Beatrice d'Este was of high noble birth and had been brought up very cultured, whereas Ludovico's military family had been raised to nobility only two generations earlier. Ludovico's life as ruler of an important duchy was therefore very much focused on maintaining power

- at the time of their marriage Ludovico's mistress Cecilia Gallerani was pregnant by him

- during the marriage he had numerous love affairs and several illegitimate offspring

- four years after the wedding he took Lucrezia Crivelli, a lady-in-waiting of his wife, as his mistress. She was pregnant by him when his wife died giving birth to their child.

In view of the unhappy marriage of Beatrice and Ludovico, it is unlikely that the duke commissioned Leonardo to paint a portrait of Beatrice.

The Milanese Duke Ludovico Sforza on the left, on the right his wife Beatrice d'Este. Beatrice's dress shows the same hanging ribbons as that of the Belle Ferroniere. This strongly suggests that the Belle Ferroniere was Lucrezia Crivelli, who dressed similarly as her lady-in-waiting.

Politically sensitive: On the left front, the illegitimate child Cesare Sforza must be depicted (*1491), whom the duke fathered with Cecilia Gallerani, the lady with the ermine. For the second son of Ludovico and Beatrice was born only one year after the completion of the altarpiece (*1495). Therefore, the painting intended for a public church must have been deeply offensive to the high noble Beatrice d'Este. The duke lost a war against France and died a lonely death in French gaol

Cecilia Gallerani

She was already portrayed as 'Lady with the Ermine' by Leonardo da Vinci. The Polish princess Izabela Czartoryska acquired the portrait around 1800 and felt a great resemblance to the painting of Belle Ferroniere. Thus, she arranged for the inscription on the 'Lady with the Ermine' in the upper left corner, which is still visible today:

LA BELE FERONIERE

LEONARD DAWINCI

(Polish spelling). That Leonardo should have portrayed Cecilia Gallerani twice, however, is considered unlikely, especially since both portraits hardly resemble each other.

Cecilia was the mistress of Duke Ludovico Sforza. She bore him a son shortly after his marriage to Beatrice, the sister of Isabella d' Este. A later owner of the painting was convinced that the lady with the ermine was "La Belle Ferroniere" and had the painting inscribed accordingly in the upper left corner

The duchess was a constant admirer of Leonardo and asked him several times for a portrait. However, Leonardo considered portraits, such as this one in full profile, to be lacking in expression and did not show them in any of his paintings

Isabella d’Este

She was the Duchess of Mantua and the elder sister of Beatrice d'Este, wife of Duke Ludovico Sforza of Milan. There is a portrait drawing which is supposed to show her and which is attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. By preserved letters it is secured that she asked Leonardo several times for a portrait. She was considered his admirer and eventually borrowed the painting "Lady with an Ermine" from Cecilia Gallerani, as is evident from their correspondence.

Since she rarely stayed in Milan, Leonardo could have painted her portrait during his longer stay in Mantua around 1500. This is further supported by the fact that in 1642 a catalog of the French royal collection mentions a portrait of the Duchess of Mantua that Leonardo da Vinci is supposed to have painted. However, this could also have been a case of mistaken identity.

Against the identification as Isabella d'Este speaks that the proud admirer of Leonardo would have certainly told her environment if she had been portrayed by Leonardo. However, such sources cannot be found.

Isabella of Aragón

She was the young wife of a nephew of Ludovico Sforza, Gian Galeazzo Maria Sforza. Gian was the actual rightful Duke of Milan, but due to his young age his uncle Ludovico exercised the regency for him. Having come of age and at the insistence of Isabella of Aragon, Gian made claims to the throne and died unexpectedly and under unexplained circumstances in 1494. He lived to be only 25 years old. The throne of Milan should have then gone to Gian's four-year-old son, but Ludovico was able to continue as duke.

Given the political circumstances at Ludovico Sforza's court, it is doubtful that Leonardo should have portrayed Isabella of Aragon.

Theory II - Mistress of the French King (Belle Ferroniere)

According to a second - completely contradictory - theory, the painting is not supposed to come from Leonardo's Milan period, but to have been created in the last three years of his life, when he was at the court of the French king. According to this, it is supposed to be one of the many mistresses of the French king Francis I.

The name of the portrait "La Belle Ferroniere" is a combination of 'La Belle' (French for 'The Beautiful') and 'Ferroniere'. Ferroniere is the name given to a narrow headband with a jewel set in it, worn in the center of the forehead. This type of headdress - narrow bands set with precious stones - was typical of the Italian Renaissance. It is often said that the Ferroniere headdress was first seen in this painting and owes its name to the sitter, a Madame Ferron, or a Ferroniere.

What is a ferroniere?

Ferroniere derives from the French word "fer" meaning "iron" and refers to a woman who is professionally involved with iron. Thus, a ferroniere could be a blacksmith or ironmonger. According to the understanding of the time, this certainly meant wife of a blacksmith or ironmonger.

The legend of Madame Ferron

The lecherous King Francis I is said to have taken the young Madame Ferron as his mistress around 1524. She is said to have been known at court by her nickname "La Belle Ferronière". Her jealous husband, the Parisian lawyer Jean Ferron (sometimes an unknown ironmonger, i.e. Ferronier) is said to have been so incensed by this that he decided to take bitter revenge. He went to a notorious brothel to deliberately infect himself with syphilis. His wife thus infected the king, who became infertile as a result. Madame Ferron is said to have died about six years later. The king, on the other hand, is said to have suffered for another 23 years until he too died in 1547.

The truth of the legend

This legend is often used to prove the existence of a historical Belle Ferroniere, suggesting that Leonardo portrayed her. This cannot be true because Leonardo da Vinci died in 1519, but the affair is said to have begun in 1524.

The legend goes back to the life stories of the French nobleman Brantôme, but is by no means historical. Rather, it was part of Brantôme's lifestyle to spread the most scandalous gossip possible about the noble houses of Europe. These shallow tales were also printed and enjoyed great popularity.

The same legend was also spread by a doctor who was quite famous in Paris. Louis Guyon seigneur de la Nauche, like Brantôme, was famous for his gossip. He also sold his books. Which is surprising, because he made it to fame and reputation as a doctor even beyond his lifetime. He introduced a special cure and published a number of specialized books. Later he was even elevated to the peerage for it.

Both Brantôme (c. 1537) and Louis Guyon (c. 1527) were still very young when Francis I died in 1547. Brantôme was only about 10 years old, Louis Guyon was already 20 years old. Both can have heard the gossip at the royal court only from hearsay, if their stories were not completely made up. It is important to mention that all the stories about a syphilis disease of Francis I can be traced back to these two. There are no other sources for an illness of the king in this respect.

The fact that the ominous syphilis disease must have been a legend is also made clear by the fact that Francis I still fathered offspring at an advanced age (Nicolas d'Estouteville, *1545).

Was there a mistress Belle Ferroniere?

There is no official source that mentions a mistress "Belle Ferroniere". Francis I was very public with his love affairs, and a historical Belle Ferroniere would therefore not have remained hidden. A mistress "Belle Ferroniere" probably never existed.

Origin of the name "La Belle Ferronière

Although the legend of Madame Ferron does not refer to the Leonardo painting, it is the reason for the painting's current name. The painting "La Belle Ferroniere" originally meant another painting of the royal collection, which is still in the Louvre under this name (Louvre, INV 786).

The painting was also in the royal collection in Fontainebleau and was originally called "La Belle Ferroniere"

This copperplate engraving with the then incorrect caption is the cause for the current designation of the Leonardo painting as "La Belle Ferronière"

The confusion by the painter Ingres

The origin of the present name of the Leonardo painting as "La Belle Ferronière" goes back to a confusion of the painter Ingres. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was a famous painter at the time of the French Revolution and a great admirer of Leonardo. A copy of his painting "The Death of Leonardo da Vinci" (1818) can be found today in Leonardo's former bedroom in Cloux Castle. Other well-known paintings include "The Turkish Bath" and numerous portraits of Napoleon.

Ingres knew the legend of the royal mistress Madame Ferron, spread by Brantôme and Louis Guyon about King Francis I, because it was still very present in French books.

Around 1802-1806, the painter Ingres collaborated with the painter Lefèvre on an engraving of Leonardo's portrait of Belle Ferroniere. They mistakenly titled the print "La Belle Ferronière." Later they claimed that they had simply made a mistake, but it is quite possible that they wanted to associate the hitherto nameless Leonardo painting with the legend of Madame Ferron in order to bring more attention to Leonardo's portrait of the unknown lady. And this is exactly what happened.

Portrait of a woman, mistakenly called La Belle Ferronnière

The copper engraving spread quickly, as it was reproduced in numerous books of the time. The legend of the cuckolded husband who lost his Madame Ferron to the king and sacrificed himself in revenge to put them both to death with syphillis fit well with the zeitgeist of post-revolutionary France, and Leonardo's Belle Ferroniere was a very nice image to go with this legend.

As a result, Leonardo's painting was one of the most visited paintings in the Louvre in the early 19th century. However, in relation to the Louvre, two "La Belle Ferronière" were now part of the exhibition. One was the original "La Belle Ferronière" by an unknown painter and the other was the one by Leonardo that Ingres mistakenly called "La Belle Ferronière".

This caused some confusion among the public and so the title for Leonardo's painting was established as "Portrait de femme, dit à tort La Belle Ferronnière (French 'Portrait of a Woman, Mistakenly Called La Belle Ferronnière'). This is still the official title of the Leonardo painting in the Louvre.

Nevertheless, the name La Belle Ferronière has generally become accepted for the Leonardo painting. The original "La Belle Ferroniere" painting is hardly known today.

The Ferroniere

Ingres' error is the cause of a narrow headband with a jewel attached to it, worn centered on the forehead, being called a ferroniere after this painting. This type of jewelry was not a Leonardo invention, but a widespread fashion in his time. It can be discovered in numerous paintings of the Renaissance.

Theory III - Mistress of the French King (petite Bande)

It cannot be excluded that the painting shows a now unknown mistress of the French king. Francis I was a womanizer. In addition to his queen and his mistresses, he also had a circle of young ladies around him who were called "petite bande" (small band). He also lived out his erotic needs with them. It is interesting that the French 'bande' can also be translated as stripes or ribbons, which could explain Belle Ferroniere's conspicuous ribbons on her dress and necklace.

It can therefore be surmised that the king commissioned Leonardo da Vinci to portray one of these ladies. The dating of the painting would then fall within the last three years of Leonardo's life, i.e. 1516-1519.

The golden lilies on the green hem

The golden embroidery of the coat of arms on the green hem of her dress speaks for a French reference of the sitter. The individual embroideries vary in fine nuances and can partly be recognized as slit lilies. This is especially evident on the lower right corner of the hem.

The lily was the emblem of the French kings. Therefore, the French national flag showed golden lilies on a white background until the French Revolution in 1789.

In addition, the lily also represents a direct reference to Leonardo da Vinci. As the 'Florentine lily' it is still the city emblem of Florence today. Leonardo da Vinci grew up and was educated in Florence.

Conclusion on the identity of the Belle Ferroniere

It has become clear what difficulties it makes to determine the identity of the Beauty.

On the whole, the most comprehensible theory seems to be that she is the last mistress of the Milanese duke Ludovico Sforza, Lucrezia Crivelli, the "lady from Milan," as the scribe Andrea de Beatis calls her. Also in view of the poem of Antonio Tebaldeo listed below, this theory seems altogether plausible. This view is then also held by the Louvre as an exhibiting museum.

That the painting is supposed to show a mistress of the French King Francis I named "Belle Ferroniere", on the other hand, seems most implausible upon closer historical examination.

However, that it is another, today unknown mistress from the circle of the "petite bande" is again very plausible due to the ribbons on the dress, as well as the golden lilies on the hem of the Belle Ferroniere.

Two mutually exclusive theories

So, according to current knowledge, there are two probable theories, but they are mutually exclusive.

Now, the painting was either painted in Milan between 1490 and 1499 and shows Lucrezia Crivelli. She arrived at the Milan court in late 1490 in the entourage of Beatrice d'Este, when she married the duke. With the invasion of the French in 1499, the Duke of Milan lost his court and Leonardo lost his patron, which means that by this time at the latest the portrait had been completed. This also explains why Leonardo had the painting of a 'Lady from Milan' when he was visited by de Beatis in 1517. He kept it in safekeeping because the actual owner, Ludovico Sforza, was first on the run and then in prison until 1508, when he died. Why Leonardo did not then give the painting to Lucrezia Crivelli is unknown.

Alternatively, it may be the portrait of a now unknown mistress of the king from the 'petite bande' circle, painted at the French court around 1516-1519.

It has been shown that both theories have plausible arguments, but a final classification is not clearly possible. The large number of plausible conjectures about the identity of the beautiful woman lead to the conclusion that Leonardo da Vinci was not interested in depicting a concrete person. For in contrast to the 'Lady with the Ermine' painted before it, the young woman was painted entirely without clearly assignable attributes that could still be known to later generations. Rather, Leonardo seems to have deliberately created a work that should unfold its magic independently of the person of the sitter. Thus, ultimately all that is known of the Belle Ferroniere is her beauty.

History of the painting

The painting was probably created between 1490 and 1519. No commission documents, notes, studies or the like are known for the portrait.

From the same wood

Here and there it can be read that the walnut wood used is the same as that of the Lady with the Ermine, and therefore must have been painted by Leonardo da Vinci in his Milan period. But this assertion could be disproved in the meantime by material researchers of the Louvre.

The travelogue of Antonio de Beatis 1517

The only vague source that links the painting to Leonardo da Vinci is the travelogue of Andrea de Beatis. De Beatis was a scribe in the entourage of the Italian Cardinal Luigi d'Aragona and had the opportunity to visit Leonardo's workshop at the French royal court in Cloux in 1517. There he reported on the painting of a lady from Milan:

"There was also a painting in which a certain lady from Milan was painted in oil after nature, which is very beautiful, but in my opinion not as beautiful as Signora Isabella Gualanda."

The remark is addressed to the contemporary public in Naples. Isabella Gualanda was famous there for her beauty. Cardinal Luigi d'Aragona was also from the city.

It goes without saying that the brief mention does not necessarily mean the Belle Ferroniere, but given the few undoubtedly genuine paintings by Leonardo da Vinci, it is very likely that the 'Lady from Milan' is this portrait (or another painting that is now lost).

De Beatis was the last eyewitness to report Leonardo's late work. His statements are considered particularly plausible, since he explicitly mentions the 'Lady of Florence' (presumably the Mona Lisa), Anna Selbritt and John the Baptist, the last three paintings of Leonardo, which he must have had with him in Amboise. And in addition a fourth, the "Lady from Milan". All four paintings are now in the Louvre in Paris.

In the royal collection

After Leonardo's death in 1519, the painting either went directly into the possession of the French king and became part of the royal collection in Fontainebleau Castle, or it was acquired at a later date. More precise details are unknown due to the poor state of sources.

The work is then first mentioned in the Fontainebleau collection from 1642.

- In 1642 Father Dan published his work "Treasury of the Wonders of the Royal House of Fontainebleau". Four paintings by Leonardo are listed there, one as "a portrait of a Duchess of Mantua" (this must mean Isabella d'Este). Of the known Leonardo portraits, only the Mona Lisa and presumably the Belle Ferroniere were in the collection. Father Dan's work thus strengthens the identification of the Belle Ferroniere as the Duchess of Mantua

- In 1651 Raphaël Trichet du Fresne included this designation in his biography of Leonardo

1682 Louis XIV has the royal collection transferred to the Palace of Versailles

- In 1683 the painter Le Brun wrote a catalog of the royal collection and referred to the painting there only as a "portrait of a woman"

- This designation was taken over in 1709 by Nicolas Bailly and in 1752 by François Bernard Lépicié, who again wrote catalogs of the collection

- In 1784, the painting is then recognized by the author Durameau in another catalog as a portrait of the English queen Anne Boleyn (1507-1536), without giving reasons for the attribution

Public exhibition in the Louvre in Paris

As a result of the French Revolution of 1789, the royal collection became the property of the French state in 1793, which put it on public display in the newly opened Louvre Museum.

- In 1802-1806, painters Ingres and Lefèvre produced a rapidly circulating engraving that mistakenly titled the painting La Belle Ferroniere. The Louvre henceforth refers to the painting as "Portrait of a Woman, Mistakenly Called La Belle Ferronnière"

The painting is now in Room 710 in the Grande Galerie of the Louvre.

Composition

The painting is represented in the usual Leonardo literature mostly cut. The exhibiting Louvre Museum in Paris shows the painting on its website complete and without frame, but unfortunately with a perspective distortion. From this photograph, the missing areas were reconstructed for this analysis. This can be seen by a slight difference in color at the edges of the wall.

In the representation shown here, the painting has the original proportions of width and height. However, the original height of the painting cannot be determined with absolute certainty, as the portrait is now slightly curved upward at the upper left edge. For this analysis, the part that curved upward was cut away to create a rectangular image. The difference is so minimal (<1%) that it does not fundamentally alter the geometric relationships in terms of image height.

Painting description

The painting is mostly shown cropped in the common Leonardo literature. The exhibiting Louvre Museum in Paris shows the painting on its website complete and without frame, but unfortunately with a perspective distortion. From this photograph, the missing areas were reconstructed for this analysis. This can be seen by a slight difference in color at the edges of the wall.

In the representation shown here, the painting has the original proportions of width and height. However, the original height of the painting cannot be determined with absolute certainty, as the portrait is now slightly curved upward at the upper left edge. For this analysis, the part that curved upward was cut away to create a rectangular image. The difference is so minimal (<1%) that it does not fundamentally alter the geometric relationships in terms of image height.

I Introductory study

The headpieces of the bands are highlighted as transparent brown ellipses.

The centre lines

The central vertical line runs exactly through the young woman's left eye (red line).The horizontal centre line is tangent to the hem of her left shoulder and the upper band of her right shoulder (red line).

The golden section

The vertical golden section cuts her right eye exactly in the centre and runs through the headpiece of the band at her neckline (orange line). The horizontal golden section also runs through the headpiece. It is also tangent to the two headpieces of the lower bands of her left shoulder (orange line).

Reference to the Lady with the Ermine

The emphasis of the golden cut in the headpiece of the band at the décolleté immediately reminds one of the golden cut in the right and left eye of the ermine in the Lady with the Ermine. Only here it is not on the right but on the left side, i.e. it is a mirror image. The two paintings are thus placed in relation to each other.

II The four image zones

From the top edge of the wall to the highest point of the young woman's head, a large square can be stretched that is as wide as the painting. To determine the centre of this square, the central perpendicular and the horizontal bisector are drawn in (centre of the picture). The square now consists of 4 equal parts. The bisector of the square must not be confused with the bisector of the painting.

On closer inspection, the viewer recognises that the rectangular jewel on the headband has been divided by the painter exactly in the middle by a line. This has created two squares lying directly next to each other (red and green square).

They thus place the ferroniere in a contextual connection with the large square and its four parts.

III The lower left quadrant

From the young woman's face the view leads down to her neck with the fourfold wrapped chain. The chain consists of black and white links of equal size. The elaborately sewn dress is clearly structured by fine lines.

The left angle of the hanging part of the necklace is 72° (green line on the left).The other part of the necklace hangs down at an angle of 45° (green line on the right).Two cross-shaped seams can be seen on the left and right of her décolleté (orange crosses). The headpiece of the ribbon at the décolleté is slightly raised above these crosses on the green hem of the dress. The hem is slanted at an 18° angle (green line horizontal).

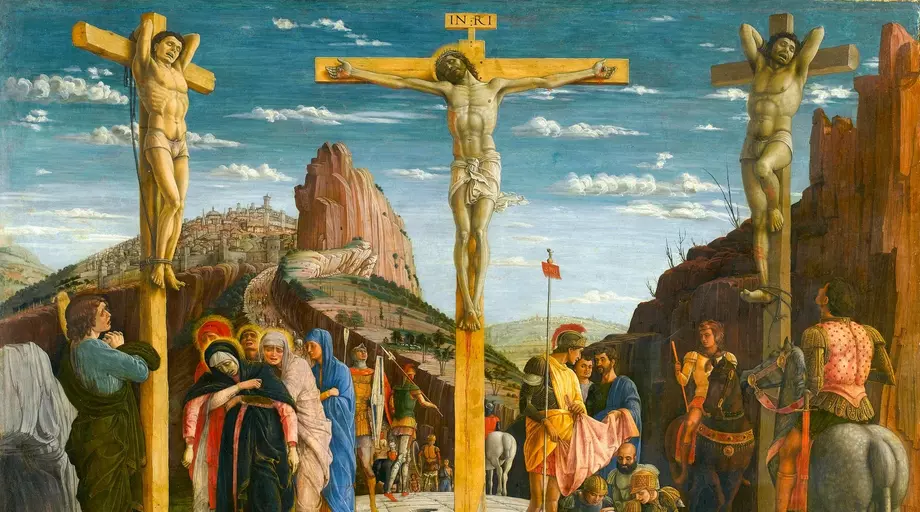

Overall, the emphasis of the lines is reminiscent of a crucifixion scene. For clarification, a flesh-coloured stylised face was painted on the crucifix for this analysis (pink). According to this, a crucifix hangs around the young lady's neck. On the left and right of her breasts, stylised crosses symbolise the two thieves mentioned in the Bible who were crucified with Jesus (Lk 23:39). In iconography, the repentant sinner who is redeemed is depicted on his right, and a convinced criminal on his left.

The other two headpieces of the bands (brown transparent ellipses) on the right shoulder are reminiscent of two other crucified persons looking towards the crucifix. In this way, it is no longer possible to determine by means of iconography which of the five crosses Jesus is on.

Since there are more than the iconographic three crosses, it even becomes unclear whether it is actually a Christian crucifixion. It could be any other crucifixion scene, for example that of the rebellious slave leader Spartacus, who was crucified along the Via Appia with 6000 other slaves.

Due to the protruding, feminine-looking hips of the figure on the crucifix, it cannot be ruled out that a woman was crucified.

Furthermore, the figure on the crucifix can be interpreted as a person stretching her arms upwards (the two links of the chain). For clarification, a green face looking upwards is painted at the beginning of the animation.

Overall, the crucifixion scene occupies the lower left quadrant of the encompassing square. The crucifix closes the scene to the right (green line horizontal). The top crucified person closes the scene upwards (top brown transparent ellipse). Both points lie exactly on the frame of the lower left quadrant.

IV The right lower quadrant

On the ribbons of the left shoulder, knots can clearly be made out with which they were fastened to the dress. The knots are arranged in such a way that they form an isosceles triangle, i.e. the left and right sides are exactly the same length (white lines). The two inner angles on the left and right are exactly 30°. The upper angle is 120°. The lower side of the triangle divides the lower right quadrant in the golden section (orange line). It is not to be confused with the golden section of the painting height, which is just above it.

For this purpose, a 60° angle can be drawn from the upper node to the base of the young woman's middle parting (yellow lines). From there, a 75° angle leads to the centre of the lower left quadrant. If you connect these three points, you get my triangle with interior angles of 45°, 60° and 75°.

The resulting triangle explains the shimmering red reflection on her right cheek: from the stylised shoulder in the form of the smaller equilateral triangle, the incident light of the large triangle (yellow) is reflected in the direction of her head.Finally, the uppermost point of the large triangle (yellow) refers to the ferroniere. The two squares in the jewel of the forehead can now be understood more specifically as symbolising the two lower quadrants (red and green square).

Looking at the neighbouring crucifixion scene in the lower left quadrant, the bands also appear humanised here. A larger figure (the middle band) stretches out its arms towards two smaller figures (left and right bands). The folded fabric of the dress in the left band also evokes associations with a sleeping person under a blanket in a bed.

V The two upper quadrants

In contrast to the lower half of the large square, no clear division into a left and right area can be seen for the two upper quadrants. Instead, the two upper quadrants are merged into a rectangle. Here again, the reference is made to the ferronniere, in the centre of which a rectangular gemstone has been placed. Its proportions correspond to two adjacent squares.

On closer inspection, the face element of the ferronier consists of six equally sized, circular gemstones arranged in the shape of a regular 6-corner in a circumcircle. The circumcircle appears oval because it has been tilted backwards by exactly 30°. In the center of this circle is the already known rectangular jewel, which was divided by the painter with a vertical line into two squares of equal size.

The headband is tilted by about 3.5° (white line). The young woman's head is also tilted upwards to the left by 3.5°, recognizable by the center of her pupils (blue line).

From where the eye axis (blue line) meets the central perpendicular, an angle of 60° can be drawn to her central vertex. From this, a tangent at the brow jewel meets the eye axis again at an angle of 45°. Again the already known triangle of 45°, 60° and 75° angle is created. But it is now vertically mirrored and tilted by 3.5°. These two triangles have the common corner point in the middle vertex (IV yellow triangle). From the center of the two squares of the rectangular jewel two lines can be drawn to the lower corners of the surrounding white triangle (V white lines). The left angle is 72°, the right one 45°.

The wall in the foreground of the picture consists of three equal parts. A keystone can be seen, which was placed on a second stone of the same height. The lower one has a strong grain running through it. Below it, a wall indented to the rear can be seen, which is clearly distinguished from the two stones above it by stronger shading.

If now only the horizontal lines thus created are considered, a universal final image emerges.

The word geometry is derived from the ancient Greek words for earth and measuring (geo and metron). By means of geometry it was already possible for the ancient scientists to measure the circumference of the earth, but also e.g. the size and distance of the moon. Until the discovery of Uranus in 1781, the six inner planets of our solar system were known since antiquity. Against this background, the six horizontal lines constructed by Leonardo appear in this scene as a stylized solar system in the center of which the forehead jewel of the eponymous ferronier has been placed (V + mouseover). The forehead jewel, in turn, also consists of six gems arranged evenly in a circle.

Concluding conclusion on the geometry of the picture

Leonardo da Vinci revealed his universal understanding of the world here in a picturesque way. He divided the picture into three sections. He constructed the young woman into a square, the lower two quadrants of which each show a crucifixion scene and a domestic scene. Above it, the two upper quadrants were combined into a rectangle in which, in conjunction with the lines of the tripartite wall in the foreground, Leonardo's universal spirit is revealed. Everything is articulated and connected by geometry. The jewel in the ferroniere is the element that connects all the scenes. It is truly a Belle Ferroniere.

Interpretation

To illustrate the idea of the picture, Leonardo used two fundamental symbols of European cultural history in the Ferroniere, which gives it its name: the Jewish-religious Star of David and the Greek-academic pentagram.

The Pentagon - A Symbol of Greek Philosophy

One of the defining themes of ancient Greek natural scientists was the attempt to prove with the golden ratio a universal mathematical constant contained in all things. They found the golden ratio in the distances of the planets, in the blossoms of certain plants and also in human proportions.

The symbol of the golden section is the regular pentagon or pentagram. The geometric construction of a regular pentagon is not trivial and for a long time was considered a secret, taught only in the ancient Greek academies. As a result, a certain mysticism is associated with the symbol to this day.

The famous polymaths Pythagoras, and later Plato (Platonic solids) were among the first to study the natural occurrences of the golden section.

The Hexagon - A Symbol of the Jewish Religion

The enduring symbol of Judaism is the Star of David. The religious aspect is underlined by the fact that the Star of David can be reduced to two equilateral triangles created by mirroring and shifted into each other. Today a religious-politically charged symbol, in the geometric sense it is a hexagon, i.e. a regular hexagon.

King David is also of great importance to Christians. This is especially evident in the fact that the New Testament lists Joseph, Mary's husband, as a direct descendant of King David (Matt. 1:1-17). The solemn entry into Jerusalem by Jesus Christ is also in the tradition of the first conquest of the city by King David, whose son Solomon built a Jewish temple for the first time ever in history.

From geometric symbolism to the image motif, beauty

Both symbols, the Star of David and the pentagram, are united at a crucial point in the painting, namely in the Ferroniere, which gives it its name, as was shown in the section on the geometry of the picture.

The basic square division of the painting into two lower quadrants and a rectangle rising above them also divides the painting on the narrative level. In the lower section, the crucifixion scene on the left and the domestic scene on the right create a clear reference to the Judeo-Christian imaginary world. In the section of the painting above, Leonardo merely focuses on the beautiful face of Belle Ferroniere, whose forehead jewel also forms the center of a stylized planetary system (V + mouseover).

The painting is now the attempt of a geometrical synthesis of Judeo-Christian and Greco-Roman symbolism and underlines the one-world idea of the universal spirit of Leonardo da Vinci. This universal genius was already thinking across denominations and nations. Quite a humanist, in the literal sense of the word, he first had to view Europe as a world of people rather than a world of peoples and religions. To convey this idea, he reduced the representation to that which is common to all people, beauty. Regardless of whether they had a Greco-Roman or Judeo-Christian background, they were united by one thing as human beings: a sense of beauty. Leonardo expresses this beauty on two levels. On the one hand, through the precise aesthetics of the underlying geometry with its interesting interrelationships, and on the other hand, through the Belle Ferroniere reduced to her beauty.

It will now be shown that Leonardo used Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian symbolism to bring the actual pictorial narrative to the viewer via pictorial geometry. It is the theme of beauty.

It is part of Leonardo's portraiture to exaggerate the representation in his paintings and to create timeless likenesses of the subjects portrayed. This is particularly impressive to see in the Mona Lisa. Leonardo did not paint a specific person, rather it is a visualization of an idea. It was important to him above all to create a timeless work of art that, free from the fashions of his time, could still be understood by future generations.

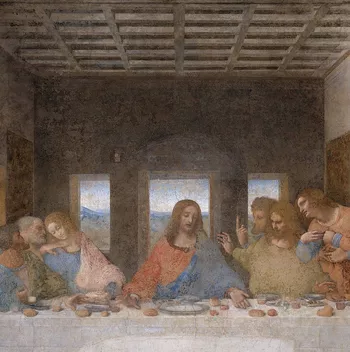

For this purpose, he made use of centuries-old stories that had proven to move people deeply. Thus he painted, among other things, the biblical figures John the Baptist and Jesus Christ together with his disciples at the Last Supper, in order to develop the greatest possible depth of meaning. At the same time, however, he refrained from overly characterizing attributes, so that the paintings can be understood even without knowledge of the biblical stories.

Although it is less obvious in his portraits of women, Leonardo da Vinci incorporated relevant cultural-historical narratives there as well. Two of these stories, whose central theme is the struggle for beauty, are thematized by Leonardo through the use of subtle accents.

The Greek Interpretation - Helen of Troy

Scholars of the ancient Greek academies in particular were known for their fascination with the golden ratio, which was repeatedly and wondrously enacted in the painting of Belle Ferroniere. If such a scholar had been asked who was considered the most beautiful woman of all time, he would have replied, "That was Helen, Helen of Troy."

Background - The Trojan War

Helena's abduction was the cause of the Trojan War. This is a probably fictional campaign of the ancient Greeks against the city of Troy. The narrative is known today only from the work "Iliad" by the Greek poet Homer (ca. 800 BC).

Homer begins his tale with a dispute between three goddesses of Olympus about which of them was the most beautiful. For a golden apple was found, which bore the inscription "For the most beautiful". The god Zeus was supposed to decide the dispute, but refused and appointed the outcast earthly prince Paris as arbitrator.

The goddesses now tried to bribe him. Hera promised Paris world domination, Athena wisdom, but Aphrodite offered him the love of the most beautiful woman in the world and won.

The most beautiful woman in the world was Helen of Troy. However, she was already married to the Sparta king Menelaus. Nevertheless, she let herself be kidnapped by Paris to Troy.

The Greeks then raised a force to bring her back. The Trojan War began. Paris was then killed by Philoctetes with a bow and arrow in the last year of the ten-year siege. Philoctetes had sailed to Troy with 7 ships.

After the death of Paris, Helen went to his brother. After the fall of Troy, Menelaus took the beautiful Helen back to Sparta.

The reference to the Belle Ferroniere

Her left unnaturally placed hair, inevitably recalls a relief depiction typical of antiquity. Leonardo has painted the lady behind a wall that must be overcome if one wants to get close to her. Her hands have deliberately not been painted by Leonardo, they are invisible and could lie tied on her lap. The view out of the fortified city could be of the Greek liberators on the ships coming to free her. The Greek attackers could have already climbed over the wall in part to climb up it in the form of ribbons. Emblazoned on the top of her forehead is the cause of the Trojan War, the circular-red symbol of beauty, the stylized apple itself. Only the inscription "For the most beautiful" is missing.

But the look into the distance could also apply to Paris, who is distorted in love for her. At the same time, she ignores all the ribbons that climb up her as much too small males just to reach the trophy on her forehead.

The Belle Ferroniere finally appears as the Trojan horse, which on closer examination reveals to the viewer the geometric treasures hidden in the painting. For out of it climb seven bands connected by the art of geometry. Surrounded by a wall that is actually not difficult to overcome, this nevertheless represents an insurmountable obstacle for many. In the spirit of Plato, who is said to have written above the entrance to his academy: "Without knowledge of geometry, no one shall enter".

The biblical interpretation - Bathsheba, wife of King David

From the 15th century at the latest, the regular hexagon became part of Jewish symbolism as the Star of David. Today it can be found on the flag of Israel, among others. It is named after the legendary Jewish king David, who - still as a boy - defeated the giant Goliath. With one of his wives, Bathsheba, he begat King Solomon, known for his wisdom. Solomon was the builder of the first Jewish temple in Jerusalem.

Background - Bathsheba

Bathsheba was originally the wife of one of David's generals, Uriah. When Uriah went on a campaign, David saw Bathsheba bathing. He had her brought to him secretly, slept with her, and she became pregnant.

David then had Uriah called back from the campaign, hoping that he would sleep with Bathsheba, which would then have explained her pregnancy. But Uriah kept away from her, referring to the solidarity with his soldiers fighting far away, who were also far from their wives.

David then sent Uriah back on the campaign and gave the secret order to have him fight in the front line against the strongest enemies. He subsequently fell in battle. After his death, David married Bathsheba. Their firstborn was cursed and died in childbirth. The second child became David's successor, the wise King Solomon. Solomon then built the first stone temple in Jerusalem.

The reference to the Belle Ferroniere

The Belle Ferroniere wears a hairnet reminiscent of a kippah, made of many circles of the same size. These circles are arranged in a hexagon. The hair of the Belle Ferroniere seems out of place, almost slipped, like a wig. Married Jewish women traditionally wear either headscarves or wigs.

In this sense, the lady's gaze is on one of the two men, Uriah or David.

If she looks at Uriah fighting in the field, the viewer looks at her as King David. Thus, she could be about to undress to take a bath VI. Secretly observed by a viewer looking through a window, but she does not see him. The impression is strengthened all the more when the two lower quadrants are covered. The Belle Ferroniere now appears unclothed, only keeping her jewelry on, as if for bathing.

Conversely, the viewer looks at her as her husband Uriah returning home from the campaign.

Her smile is then directed at King David, whom she, suspecting her pregnancy, looks upon with confidence. Her possibly pregnant belly is covered by the wall.

The unfinished wall in the foreground refers as an allegory to the construction of the foundation of the first Jewish temple by Solomon, the second son of David and Bathsheba.

Conclusion to the picture interpretation

It is impressive to see how Leonardo has composed the picture with very few stylistic means. Above all, it is surprising with what ease he relates two great themes of European cultural history. Leonardo da Vinci has shown here that behind the initially visible plane there are other levels of meaning that could appear arbitrary and random if they did not have the all-connecting element, geometry.

According to legend, at the entrance of Plato's Academy there was an inscription: "Without the knowledge of geometry no one shall enter". Leonardo knew this legend and he also adopted this motto in this painting. If it were not for the underlying precision of the painting's geometry, it would be impossible to make tangible the forebodings and associations that the painting provides to the fleeting viewer. Geometry, however, provides the key to deeper understanding here.

How well the high art of nature corresponds here! Da Vinci could have depicted the soul, as he often did. But he did not, so that the picture might be a good likeness. For il Moro* alone possessed her soul in his love.

She who is meant is called Lucrezia, and to her the gods have given everything with a rich hand. How rare her figure! Leonardo painted her, il Moro loved her: The one the first among painters, the other the first among princes.

Surely the painter has offended nature and the high goddesses with his picture. It angers them at last that the human hand is capable of so much. Rather that immortality was bestowed on a being that should perish quickly. He did it for love of il Moro, for which il Moro protects him. Both gods and men fear to anger il Moro.* il Moro (Engl: the Black or the Moor), was the nickname of Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan.

Downloads

Sources

Website of the exhibiting museum: Louvre-Museum, Paris

Frank Zöllner, Leonardo, Taschen (2019)

Martin Kemp, Leonardo, C.H. Beck (2008)

Charles Niccholl, Leonardo da Vinci: Die Biographie, Fischer (2019)

Johannes Itten, Bildanalysen, Ravensburger (1988)

Gustav Schwab, Sagen des klassischen Altertums - Vollständige Ausgabe, Anaconda Verlag (2011)

Die Bibel, Einheitsübersetzung, Altes und Neues Testament, Pattloch Verlag (1992)

Highly recommended

Marianne Schneider, Das große Leonardo Buch – Sein Leben und Werk in Zeugnissen, Selbstzeugnissen und Dokumenten, Schirmer/ Mosel (2019)

Leonardo da Vinci, Schriften zur Malerei und sämtliche Gemälde, Schirmer/ Mosel (2011)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/b/csm_leonardo-alle-gemaelde_2dc4b01ef6.webp.pagespeed.ce.ohfmgl8OfF.webp)