Leonardo da Vinci – All paintings

How many paintings did Leonardo da Vinci paint?

Leonardo da Vinci probably completed only less than ten paintings. Around 1900, about 100 paintings were attributed to him, today there are only about 20. And also for many of the remaining paintings, the authenticity is highly disputed. Of Leonardo's completed paintings, only five or seven can be safely attributed to him based on historical sources and stylistically: The Madonna of the Rocks, The Last Supper, Anna Selbritt, Mona Lisa and John the Baptist. Even if there are isolated doubts about the authenticity, the Lady with the Ermine and the Belle Ferroniere are accepted by the majority as works by Leonardo.

Why did Leonardo paint so few paintings?

Leonardo da Vinci was not a full-time painter. Rather, he was a polymath and engineer who was also known for his painting. Thus, Leonardo was always busy with other commissions and had little time for painting. But when he did take the time to create a painting, the work had to be particularly beautiful and unique. He was known to work on a painting for several years.

If you are not a mathematician, do not read my principles.

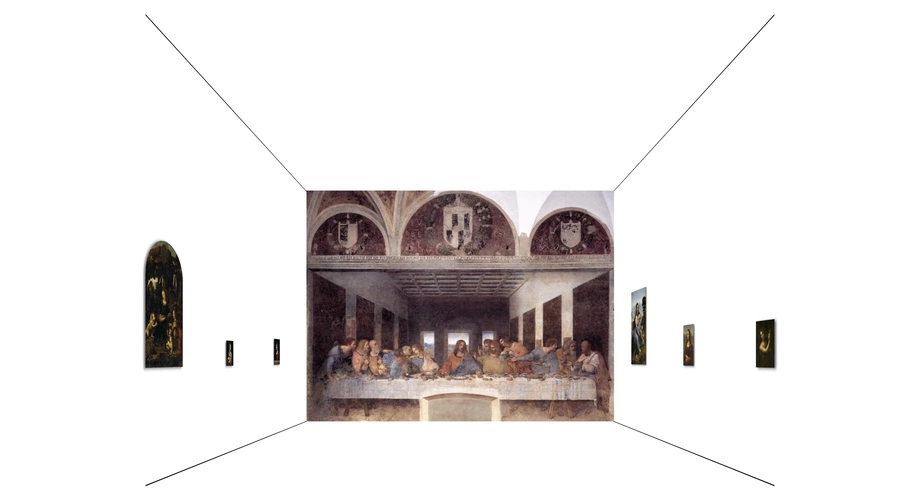

All 22 attributions - An overview

Today, about 20 works are attributed to Leonardo. For the majority of the paintings, Leonardo's authorship is disputed.

Leonardo was 20 years old when he completed his master's examination and was accepted into the Florence painters' guild. Nevertheless, he worked for his teacher Verrocchio for almost another ten years. Much of the disputed work comes from this period. The fundamentally sparse and imprecise historical sources on Leonardo's works have always left much room for interpretation and attribution.

Nevertheless, a certain style can be discerned in some of these paintings that is very different from the others. It is that graceful perfection in pictorial design that seems to be unique to Leonardo. Therefore, it can be assumed that the circle of originally more than 100 paintings, which were still attributed to Leonardo around 1900, will continue to diminish in the future.

In this overview, all paintings are listed for which Leonardo can be considered the author according to the current state of research.

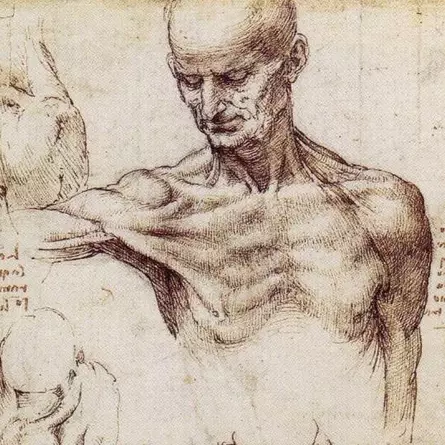

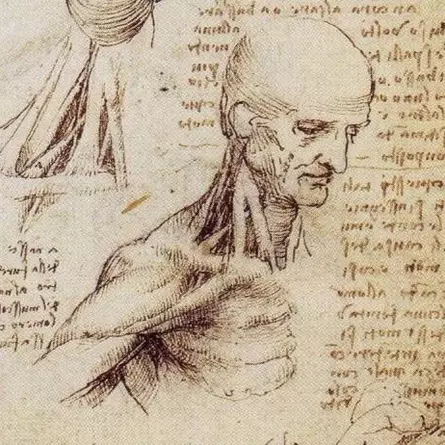

Saint Jerome in the Wilderness , about 1478-1482

The emphasis on the facial and shoulder muscles is reminiscent of Leonardo's drawings for the anatomical studies

Adoration of the Magi , about 1481

With this work Leonardo imitated a famous painting by his former classmate Sandro Botticelli.

Virgin of the Rocks , 1483-1486

Due to a legal dispute, a slightly modified version was later made by Leonardo's workshop

Lady with an Ermine , about 1490

A mistress of Leonardo's long-time employer, the Duke of Milan

La Belle Ferroniere , about 1490

This portrait also probably represents a mistress of the Duke of Milan

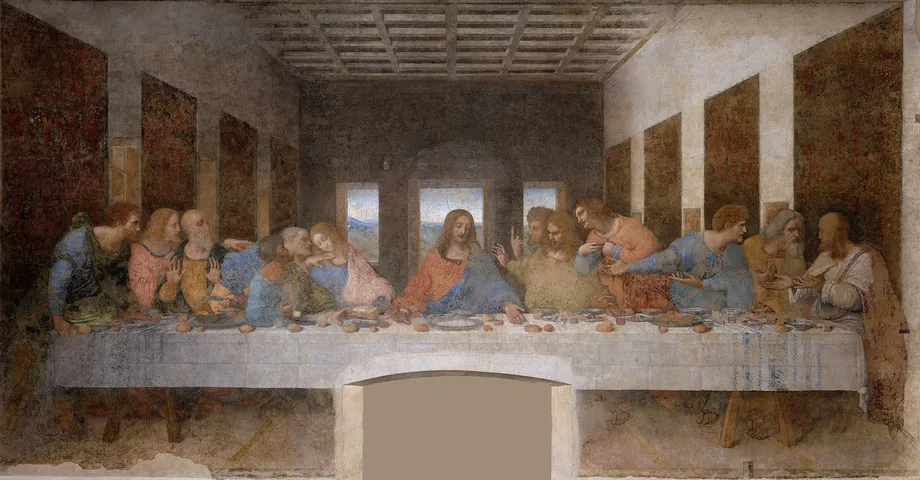

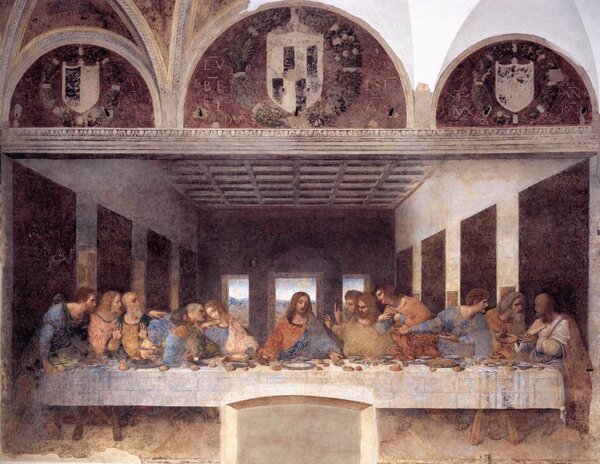

The Last Supper , about 1495-1498

The only mural by Leonardo besides the unfinished "Battle of Anghiari"

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne , about 1502-1516

There is an older preparatory study for the painting, the Burlington House carton

Tavola Doria (Study of the Battle of Anghiari) , about 1503-1505

The work on the huge mural was stopped because of wall wetness. It was then presumably bricked up and is known today only through this preliminary study, presumably in his own hand

Bacchus , 1510–1515

Today the painting is considered a work from Leonardo's workshop

Ginevra de' Benci , 1474-1478

The grandiose portrait is strikingly brilliant for the only 22-year-old Leonardo

Madonna with the spindle , 1501

The painting from Leonardo's workshop was copied by numerous students

Madonna with the carnation , about 1473–1478

One of the disputed attributions that can only be traced back to Leonardo's famous biographer Vasari

Madonna Benois , about 1475–1478

The striking religious symbolism is very untypical for a work by Leonardo

Madonna Litta , 1490–1495

Today hardly recognized as genuine, for the sake of completeness still with listed

Tobias and the angel , about 1470–1475

Leonardo is said to have painted the dog, the fish and the curls of Tobias

The Annunciation , 1472-1475

Leonardo probably painted only parts of the angel and the landscape

Baptism of Christ , about 1475

Leonardo probably painted only parts of the left angel and the landscape

Portrait of a young man (Portrait of a musician) , 1485–1490

For a Leonardo work, the lack of compositional sophistication is astonishing.

Salvator Mundi , about 1500

The most expensive painting ever sold at auction ($450 million)

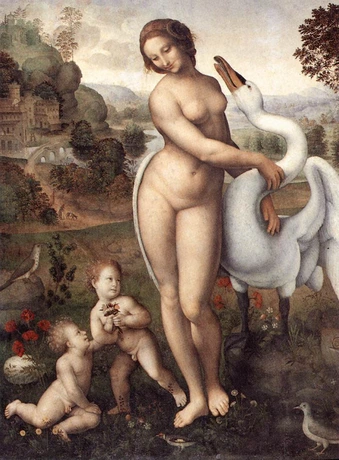

Leda and the Swan

Until today it could not be proven that Leonardo ever painted such a painting. Here is a fictitious reproduction of an unknown artist

Why is the authenticity of Leonardo's paintings so controversial?

- Leonardo never signed his paintings, this was not common in the Renaissance

- Leonardo wrote down a lot, but there are very few historical sources about the paintings he worked on

- Leonardo made very few preliminary drawings or studies of his paintings that could be used to prove that he worked on the Mona Lisa, for example. He almost never mentioned his paintings in his notes, there are occasional mentions of the Last Supper or the Battle of Anghiari, but often only in connection with the difficulties of the project

- there are very few reliable documents or eyewitness accounts of Leonardo's paintings. And when they do exist, they are very vague in their description of the paintings. For example, there are three contemporary descriptions of Anna Selbdritt, but none of them can be clearly attributed to the two known works

- there is still no reliable scientific method to date paintings before the 18th century exactly. At best, one can limit the period of origin to +/- 50 years by physical methods (radiocarbon method). This makes it very easy for forgers to put supposedly old paintings on the art market

- Due to the immense monetary and prestige value of Leonardo paintings, there are various parties who have an interest in asserting the authenticity of a Leonardo painting by means of appealing expert opinions (museums, art dealers, art forgers, art collectors)

- Leonardo is still considered the best painter of all time. Therefore, many great painters have measured themselves with him and copied his style. For them, it was then a great satisfaction when their work is recognized as a work of the great Leonardo da Vinci. Famous painters who eagerly copied Leonardo are, for example, Raphael, Rubens or Dalí

The undoubtedly real paintings

In chronological order

Virgin of the Rocks

1483-1486

Oil on wood, 122 × 199 cm, aspect ratio: golden section

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Leonardo's first completed painting was planned as a center panel for an altar that he was to decorate with two other painters. The commissioning monks were disturbed by the ambiguous facial expressions and gestures, which they considered heretical. A dispute arose over payment for the work. The painting was not handed over. A decades-long legal battle began, the result of which was a second version. It was probably no longer made by Leonardo himself, but by his workshop.

Lady with an Ermine

around 1490

Oil on wood, 39 x 53 cm, aspect ratio: 3:4

Krakow, Czartoryski Muzeum

Leonardo's first portrait of a woman shows a mistress of the Duke of Milan, Leonardo's long-time employer. The ermine is an allusion to the surname of the sitter and to the duke. The latter was a member of an ermine order.

La Belle Ferroniere

around 1490

Oil on wood, 45 x 63 cm, aspect ratio: 3:4

Paris, Musée du Louvre

The identity of the beauty with the many ribbons on her dress has not been clarified beyond doubt. Presumably, it is another mistress of the Duke of Milan. A distinctive feature of the painting is the demarcating wall in the foreground. The headdress she wears is called ferroniere.

The Last Supper

around 1495-1498

Oil on tempera on plaster, 904 x 422cm, aspect ratio: 2:1

Milan, Santa Maria delle Grazie, Refectory

By far Leonardo da Vinci's greatest work, it is the only one of his completed works to depict architecture. The mural was the last commission from the Duke of Milan shortly before he was deprived of his power and is considered Leonardo's central major work, but today it is in serious danger of decay. Leonardo experimented with colors. The painting shows the scene in which Jesus announces to his disciples at the Last Supper that he is betrayed by one of them. They are horrified and want to know who the traitor is.

Virgin and Child with Saint Anne

around 1502-1516

Oil on wood, 130 x 168 cm, aspect ratio: 2:3

Paris, Musée du Louvre

For a long time it was assumed that the work was created at the request of the French royal family. Today it is assumed that Leonardo painted the work on his own initiative. Depicted is the young Jesus, playing with a sheep. His mother Mary is sitting on the lap of her mother Anna. A second, earlier version exists, which was created as a study for this painting (Burlington House cardboard box). The psychologist Sigmund Freud referred to this painting in his famous Psychoanalysis of Leonardo da Vinci.

Mona Lisa

1503-1506

Oil on wood, 53 x 77 cm, aspect ratio: 2:3

Paris, Musée du Louvre

The Mona Lisa is the most famous painting in the world. Originally it depicted a lady from Florence, but over the years Leonardo transformed it into a mystical work through countless overpaintings. The darkly held picture creates an almost ghostly atmosphere through the eroded landscape in the background and the restless fingers of her right hand, which is countered in a wonderfully gentle way by her famous smile.

John the Baptist

around 1513-1516

Oil on wood, 56 x 73 cm, aspect ratio: 4:5

Paris, Musée du Louvre

The biblical figure John the Baptist was the patron of Florence, Leonardo's hometown. Probably Leonardo's last painting was created during his stay in Rome in the service of the Pope, six years before his death. It shows all of Leonardo's ability to achieve an astonishing complexity with the fewest means. He refrains from depicting landscape, architecture, further figures or splendid robes and works exclusively with the soft summer fur of an ermine, a human body, a cross and light. The painting is thus a wonderfully artfully visualized epigram and certainly a final greeting from Leonardo, the best of all painters.

A clear pattern is recognizable: a large painting was followed by two smaller portraits. The Last Supper is the largest painting, 9 meters wide, and was painted in the middle of Leonardo's creative period. It is also Leonardo's only completed wall painting and is thus firmly bound to the place where it was painted.

The clearly recognizable pattern of the picture sizes suggests that Leonardo interwove all his undoubtedly genuine and completed paintings as a painting cycle. Accordingly, those paintings of the universal genius must be connected by a common theme. The thesis is supported by the fact that John the Baptist is shown only in the first (Madonna of the Rocks) and the last painting (John the Baptist). In the first one as an infant, in the last one as an adult. John the Baptist is the patron saint of Florence, Leonardo's hometown and a symbol of light.

The best of all painters

Leonardo is still considered the best painter of all time. His works cannot be compared to anything that came before him. He significantly influenced many famous painters, including Rafael, Peter Paul Rubens and Salvador Dalí, to name a few. Leonardo introduced numerous innovations to painting.

Leonardo's innovations

- Leonardo developed a special painting technique, the "Sfumato". In this technique, oil paints were used to apply many very thin layers of paint on top of each other, so that hardly any clear contours are recognizable. In this way, light moods could be depicted very realistically

- Leonardo attached great importance to understanding what he saw. His paintings are always an expression of his scientific knowledge, e.g. of the propagation of light (the reddish shimmering reflections on the cheek of Belle Ferroniere)

- due to his anatomical studies it was possible for him to achieve previously unknown anatomically correct depictions

- Leonardo placed man and nature in the foreground in his paintings. For example, he placed the Madonna unusually in front of a cave surrounded by water, rocks and plants, the figures of Anna Selbritt are completely free in a landscape

- Leonardo was the first who really succeeded in making the essence of the painted persons tangible by painting them with characteristic facial expressions, gestures and attributes

- Leonardo's figures are always captured in the moment of a movement. Often they are rotated around their own axis. In doing so, they are so precisely balanced that it is difficult to tell in which direction they are turning. The balance or a harmony of movement was important to Leonardo. For example, one palm of Jesus' hand in the Last Supper points upward, while the other points downward. This dynamic representation of the figures was novel and replaced the immobile, statuesque representations of previous painters

- he discovered the principle of aerial perspective, which makes distant landscapes in paintings appear much more spatial. This refers to the fading and blueness of the air with increasing distance

- Leonardo attached great importance to geometric harmonies in the construction of his paintings. Although this was true of all the great painters of the Renaissance, Leonardo's designs are extraordinarily simple and elegant.

The second look

Leonardo was a master at getting people to take a second look at his paintings. He used a variety of techniques to do this. The most striking are supposed errors of representation. For example, in the Mona Lisa, the perspective of the Mona, the wall, and the landscape do not match; John the Baptist is missing his right collarbone; and in the Belle Ferroniere, the Ferroniere (the jewel on the forehead) that gives the painting its name is so small that one must look very closely to see it. This second look then leads to another detail, which leads to another, and so on. Leonardo's art is to completely control this process of opening up the paintings. He directs the attention of the viewer in a uniquely elegant way.

The Unfinished Paintings

In chronological order

Saint Jerome in the wilderness

around 1478-1482

Oil on wood (walnut), 103 x 137 cm, aspect ratio: 3:4

Vatican Pinacoteca, Rome

The work shows the saint surrounded by rocks with a lion, which according to legend he tamed. He is looking at the sketch he has begun of a church similar to one completed in Florence at the time (Santa Maria Novella).

Leonardo probably began his career as an independent painter in Florence with this altarpiece. It is then Leonardo's first independent painting. At that time he was about 26 years old. He initially had great difficulty in obtaining lucrative commissions and probably received the commission for the altarpiece through the mediation of his father, who worked as a notary for the clients. Due to his move to Milan (1482), Leonardo was unable to complete the work.

Since there are hardly any historical sources that connect the work with Leonardo, its authorship is primarily justified stylistically. For it can already be seen in this early work that Leonardo was striving for a harmony of science and painting. The emphasis on the bones and musculature of the saint indicate that Leonardo had extensive anatomical knowledge even at a young age.

The painting was unknown for a long time until it was rediscovered in Rome by an uncle of Napoleon. It had been cut into several pieces that served decorative purposes. This can still be seen clearly in the square-shaped dark discoloration around the head.

This drawing is on the same sheet below

Adoration of the Magi

around 1481

Oil on wood

247 × 246 cm, aspect ratio: 1:1

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

The painting shows the Madonna shortly after the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem. She is surrounded by believers. Among them are the Magi from the East. They come to worship Jesus. In the background on the right, a battle is raging that is strikingly similar to the depiction of the "Battle of Anghiari" that began about 20 years later. The left half of the background of the painting is devoted to the perspective depiction of architecture, which Leonardo otherwise shows only in his major work, The Last Supper, about 15 years later.

A special feature of the painting is its reference to Sandro Botticelli's Adoration of the Magi, painted a few years earlier. The latter was a fellow student of Leonardo in Verrocchio's workshop, but seven years older. Botticelli depicted himself in his version on the right edge. Therefore, conjectures arose that Leonardo also depicted himself on the right edge in his work.

Like the work "St. Jerome in the wilderness", which was begun at the same time, Leonardo had to leave this painting unfinished in Florence when he left for Milan to serve the Duke there.

Botticelli was a fellow student of Leonardo's with Verrcochio. It is believed that he portrayed himself in the right margin

Since the subject of the painting is very similar, it is assumed that Leonardo also portrayed himself here. In his writings, Leonardo was critical of Botticelli's painterly quality at least twice

Tavola Doria (Study of the Battle of Anghiari)

around 1503-1505

Oil on poplar wood, 86 x 115 cm, aspect ratio: 4:3

Touring exhibition

The wooden panel (Ital. 'Tavola') was named after its former owners, the Doria family. It is highly probable that it was Leonardo's own study for the oversized mural "Battle of Anghiari".

The painting was planned for the Hall of 500 in the Palazzo Vecchio, the city parliament of Florence. It was to commemorate a glorious victory that the Republic of Florence had won over the Duchy of Milan 60 years earlier.

At the same time as Leonardo, Michelangelo began his painting of the Battle of Cascina in the same room on the opposite wall. But both works made little progress because of wall wetness. Leonardo had made attempts to dry the walls, but succeeded only poorly. His notes testify to the difficulties of the project:

"On Friday, June 6, 1505, at the stroke of thirteen o'clock, I began to paint in the Palazzo. The moment I set the brush, the weather turned bad and the bell of the court sounded to call people to the hearings. The box tore, the water was spilled, and the vessel in which the water was brought broke. And immediately the weather turned bad, and it rained in torrents until evening, and it remained as dark as night."

Both painters were called away from the unfinished works. Leonardo suddenly had to return to his employer at the time, the French governor in Milan, and Michelangelo followed the Pope's call to Rome. It is unknown whether the two works ever went beyond preparatory studies, because only copies of preparatory cartoons exist for Michelangelo's planned painting as well.

Michelangelo's work is also considered lost and is preserved only through copies made later by his students. It shows bathing warriors surprised by an alarm. The motif of water and hasty escape brings to mind the specific difficulties of the project with the damp walls. Michelangelo also had to leave the project suddenly

The planned dimensions of the huge mural are unknown, but it would certainly have been at least as large as The Last Supper. The Palazzo Vecchio was extensively renovated and rebuilt about 30 years later. Among others, the famous Leonardo biographer and architect Giorgio Vasari carried out the construction work. He painted several paintings in the Hall of 500, which were about 13m wide and 7m high. Presumably Leonardo's and Michelangelo's works should also correspond to this size. For comparison: Leonardo's largest painting by far is the Last Supper, about 9m wide and 4.5m high, also a wall painting.

The "Tavola Doria" was Peter Paul Rubens' model for his version of the Battle of Anghiari (after Leonardo da Vinci).

This drawing is the best known copy of the lost painting. Probably the Tavola Doria is the model of all copies. Remarkable is the similarity of the lower left face to Leonardo's presumed self-portrait in the "Adoration of the Magi", which seems to be slinking away from the battlefield in anticipation of a hopeless fight. It almost seems as if both Michelangelo and Leonardo had already worked out the presumed difficulties of the project in the picture design. It is not surprising that the Palazzo Vecchio was extensively renovated a few decades later

Leonardo's painting

Leonardo's painting was revolutionary. The new, lively and naturalistic style must have had an extraordinary effect on his contemporaries. Realistic portraits with a high degree of detail were already known from Dutch painting in the 15th century (Memling, van Eyck, van der Goes). Leonardo's effect, however, went far beyond a realistic impression. He always knew how to masterfully satisfy all the demands of the sitter and, in addition, to weave the many layers of meaning peculiar to him as timeless components into the finished picture by means of an elegant pictorial composition. Other painters also succeeded in this. Leonardo's achievement lay in having developed such a multi-faceted personality that no other painter can equal his final work. His formal innovations will now be explained.

Development of the Sfumato Style

His oil painting is still considered technically perfect today. In order to depict the transitions of the colours, he constantly improved the composition of the oils and pigments, which were to appear particularly clear and colour-fast. Characteristic of the Sfumato style is the most exact imitation of natural shadow colours, especially at the edges of the objects. He applied countless fine layers of paint on top of each other. This creates a soft, elegant and very natural-looking colour impression at the colour transitions. However, the realisation of the very fine shadings is very time-consuming and requires an extraordinarily high understanding of light incidence and reflection. Leonardo's last work John the Baptist is the most luminous example in this respect. The layers of paint have been applied so finely that no brushstroke is discernible.

Anatomically Correctly Painted Bodies

Through his anatomical studies, Leonardo had extensive knowledge of the human body, its proportions and the shaping of muscles in movement. He believed that one had to understand what one was painting. Otherwise, for example, the depiction of tense muscles during a certain movement would look unnatural and reduce the overall impression of the painting.

Dynamic body movements for the first time

Leonardo developed a new style of portraiture which is characterised by the fact that each part of the body picks up and continues the movement of the one below it. This creates a dynamic overall impression that makes the viewer think that the portrait is reacting to him. This can be seen clearly in the Mona Lisa. She is sitting on a chair, her legs point away from the viewer, the torso is already more turned towards it, the shoulders even more, the head takes up the movement and finally the eyes are directed directly towards the viewer. He also applied this principle in group pictures, as can be seen well in the Anna Selbdritt.

Man in the Landscape

Leonardo was the first of the painters to interweave people and surrounding nature on an equal footing. The paintings "Madonna of the Rocks" and "Anna Selbdritt" are exemplary here. Man is not only composed in front of a landscape and the landscape is not only composed with people. Instead, in Leonardo's work, man and nature are in a reciprocal relationship. Thus the colours and forms of Anna Selbdritt are repeated in the landscape behind her. His scientific philosophy of an all-encompassing whole is thus expressed.

Discovery of the aerial perspective

His depiction of the air bears witness to a scientific study of optics and the refraction of light. He was the first to recognise the fading and blueness of air with increasing distance and to incorporate this into his paintings. He called this phenomenon aerial perspective. Alongside central perspective, it was a completely new way of depicting distances. An application of this principle can be found in the background landscape of "Anna Selbdritt".

Epic pictorial narratives

Leonardo's paintings achieve a unique density of content that has never since been matched by other painters on such an epic scale. The well-known discussion about the mystery of the Mona Lisa represents only a minimal aspect of his oeuvre. He inimitably intertwined his scientific, art-historical, biographical and political stories in each and every one of his paintings with the same stories of the sitters. Through his reduction to the common, he always succeeds in telling a story that is timeless. An example of this is his consistent renunciation of iconographic patterns. His paintings, initially characterised as religious, reveal themselves on unbiased observation as timeless scenes of human interaction, which can, however, also be understood in religious terms.

Extensive use of conundrums

Leonardo hid additional images in his paintings that extend the level of content. For example, a tree may initially appear as a tree, but then in a different context it appears as a hidden head. Leonardo thus applied the principles of Gestalt psychology long before there was a name for it. He certainly did not invent these conundrums; enigmatic images existed before, but the elegance and aesthetics with which he combines them are unrivalled to this day due to his diverse knowledge. The famous painter Salvador Dali (1904-1989) was later to give this method of developing layered narratives of images the name "critical paranoia".

Deliberate errors in representation

Leonardo liked to incorporate errors into his representations. Examples include the head of "John the Baptist", which is too small in perspective, the hand of the "Lady with the Ermine", which is too large, or the horizon line of the "Mona Lisa", which is set too high. In view of Leonardo's expertise, it can be fundamentally ruled out that this was a matter of inadequate skill. Instead, with these he gives us indications of an intention of the painting. Under the aspect of pictorial narrative, the pictorial errors thus serve as a starting point for a voyage of discovery into da Vinci's pictorial universes.

How were Leonardo's paintings created?

Leonardo wrote that the paintings had already been created in his mind's eye, he only had to realise them. This explains why he did not make any preliminary drawings. However, this first idea for a painting was by no means final. Leonardo constantly revised his paintings. The constant changes during the creation process are well documented by radiological examinations.

Leonardo began his paintings directly on a wooden panel, where he worked his way through primers, outlines, light-dark definitions and countless layers of paint in continual revisions to the final state of the work. He used the new sfumato style that he had developed. He applied the finest layers of oil paint. Oil paints have the advantage that they appear more natural than the tempera colours that were common in Italy at the time. On the other hand, oil paint dries very slowly, which enabled him to make changes afterwards. The painting process could thus take years.

Although Leonardo was one of the first painters in Italy to work with oil paint, this method had already been practised in the Netherlands.

Leonardo's studies of his paintings

Leonardo da Vinci was so confident in design and technique that he did not need preliminary sketches. Except for the Last Supper, the Battle of Anghiari and Anna Selbdritt, no sketches or studies can be found for his paintings.

Studies for the Last Supper

In the case of the Last Supper, he made a series of facial studies, as well as studies on the grouping of the disciples. Although Leonardo enjoyed the confidence of the commissioning Duke of Milan, it is conceivable that the churchwarden in whose church the work was to be created did not want to be presented with a fait accompli on the delicate question of the depiction of Jesus. Accordingly, he could have asked for sketches in advance to see what Leonardo was planning. It is also possible that Leonardo made studies because of the enormous dimensions of the work (9 x 4m) and the many people in the painting, in order to be clear about the details of the many faces. In the end, he had to invent them for lack of a real model. He describes this procedure in his notes. When walking, one should pay attention to the faces of the people one meets and remember their proportions, then one can easily put them down on paper when returning and use them later. Presumably, the face studies for the Last Supper are the result of his walks in search of suitable models for the apostles of the Last Supper. The face of Judas, on the other hand, is said to be modelled on the local churchwarden.

Studies on the Battle of Anghiari

The same could be true of sketches for the Battle of Anghiari, which was also very large in scale (7 x 4m), and where the Florence city government, as the client, required a design in advance. The much smaller Tavola Doria may have resulted from this requirement.

Studies of Anna Selbdritt

The famous cardboard for the first version of Anna Selbdritt (Burlington House cardboard) is certainly not to be understood as a preliminary study, but was probably also a requirement of the patron, the royal court of France, in order to get an impression of the picture idea in advance. In the case of the study sheets for Anna Selbdritt, they are probably copies made by admirers. The authenticity of Leonardo da Vinci's sketch sheets is very difficult to prove and in detail even more controversial than the attribution of his paintings.

For which Leonardo paintings do no studies exist?

In this context, it should be mentioned again that there are no preparatory drawings for the Madonna of the Rocks, the Lady with the Ermine, the Belle Ferroniere, the Mona Lisa or John the Baptist. All these works were created directly on the respective wooden panel.

Why did Leonardo paint so few paintings?

Until 1900, more than 100 paintings were attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, now there are only 20, the attribution of which is still largely disputed. But why did Leonardo da Vinci, the ingenious creator of the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper, paint so few pictures?

Leonardo was not a full-time painter

For a long time, the fact that Leonardo did not finance his life as a painter was overlooked. Painting was only one of his many talents. His employers always used him as a universalist. The production of paintings was only a secondary task. Rather, he was paid to contribute to improving the quality of life in the places where he worked. This was done in many ways. In times of peace, he organised courtly festivities, beautified the parks, drew up city plans, repaired dilapidated buildings, supervised construction work on urban projects, oversaw canal work, took care of waste disposal and the like. In times of war, he was employed as a fortress builder and war engineer.

The fact that Leonardo did not see himself as a full-time painter is stated in his famous letter of application to the Duke of Milan.

Quality over quantity

When Leonardo decided to complete a painting, he attached the utmost importance to quality and sometimes spent years on the work. His already limited time did not allow him to complete many paintings. Nor was it necessary to paint more pictures. Leonardo needed only a few paintings to express what others could not do with hundreds of works. The Mona Lisa is an outstanding example of Leonardo's demand for quality. He worked on this work for over 10 years and through constant overpainting and condensation created a figure that only remotely resembles the one originally depicted. In Leonardo's opinion, this quality in a painting could only be achieved if the painter focused his mind on one work instead of spreading it over hundreds of works.

The legend of Leonardo starting everything and finishing nothing

In art history, it is often assumed that it must have been impossible for Leonardo to maintain a large workshop operation with several servants and permanent employees by accepting so few commissions. One explanation was usually found in the legend that he started a lot but finished very little. Thus he would usually have received money in advance and then moved on without having achieved anything. A few unfinished paintings are cited as proof, as well as the turmoil surrounding the equestrian statue for the Duke of Milan. But case by case, and on closer examination, it is easy to find comprehensible reasons why one or the other was not finished.

Example 1: Leonardo's equestrian statue

The oversized equestrian statue is a famous example. Leonardo had already made a plaster model of this mammoth project, over 7m high, in its original size. The model was already on central display in Milan. Likewise, the bronze needed for the final casting had arrived in Milan. It was several tons. But the Duke was waging a war against France and now needed the bronze for his cannons. The completion of the statue was postponed. The duke lost the war, was deprived of power and Leonardo was unable to realise his work. The plaster model was destroyed by the French.

Example 2: Leonardo's notes

Another example is Leonardo da Vinci's extensive writings, over 4000 sheets have survived. In them, he addresses many topics without elaborating on them in detail. The reason for this, as he himself writes, is the lack of time. He trusted that his writings would be duplicated and disseminated to inspire subsequent generations to continue thinking about the multitude of his ideas, approaches and experiments.

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/b/csm_leonardo-alle-gemaelde_9c2c41714f.webp.pagespeed.ce.C2me-pV1mN.webp)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/7/csm_leonardos-fabeln_9df3358564.webp.pagespeed.ce.Mi4Wo6pyru.webp)