Sometimes, however, beauty, kindness and virtue are united in a single person in such a supreme way that, wherever he turns, every one of his actions appears divine, all other mortals lag behind him and it is clearly revealed: his achievement is donated by God, but not achieved by human skill. This was recognized in the case of Leonardo da Vinci, who, besides the never enough praised physical beauty, had a more than infinite grace in everything he did.

Leonardo da Vinci

Who was Leonardo da Vinci?

Leonardo da Vinci was an Italian painter, sculptor, architect, engineer, inventor and naturalist. He is considered the greatest painter of all time. He created the Mona Lisa, the most famous painting in the world.

What nationality was Leonardo da Vinci?

Leonardo da Vinci was Italian. He lived in Florence, Milan and Rome. He spent the last three years of his life in Amboise, France.

When did Leonardo da Vinci live?

Leonardo da Vinci lived from 1452-1519, about 550 years ago. The era in which he lived is now called the Renaissance. Renaissance comes from the French and means rebirth. What is meant is the rebirth of knowledge from Greek and Roman antiquity that was actually thought to have been lost. For example, high quality ancient statues were discovered during construction works, ancient writings of Greek philosophers were found in bibliotheques and the engineering achievements of ancient Roman builders were remembered. The people of the Renaissance then tried to surpass the ancient models. Besides Leonardo, Donatello, Botticelli, Michelangelo and Raphael are famous artists of the Renaissance.

How did Leonardo da Vinci look like?

Leonardo da Vinci is described in all sources as tall and handsome. He always dressed in noble robes. He attached great importance to cleanliness and a well-groomed appearance. Leonardo paid attention to carefully coiffed hair and perfumed himself with the scent of roses and lavender. His whole appearance had something sophisticated. Although there is no confirmed portrait of him, these three representations are often assumed to be portraits of Leonardo.

Franceso Melzi was a long-time student of Leonardo. His drawing shows with high probability Leonardo at the age of about 55 years

Long thought to be a self-portrait, the drawing is increasingly viewed critically because the person depicted is more likely to be around 80 years old. Leonardo, however, was only 67 years old

Although often used in literature, the painting was made only about 100 years after Leonardo's death. The painter could not have known what Leonardo looked like and probably based his work on Melzi's drawing (first image on the left)

What was Leonardo da Vinci's real name?

Leonardo's full name is Lionardo di Ser Piero da Vinci.

- Lionardo is the Italian form of Leonardo. He signed his first datable drawing of 1473 ("Drawing of a Landscape") with Leonardo

- in Italy it was customary to give the first name of the father after the first name. Leonardo's father's name was Piero, hence Lionardo di Ser Piero da Vinci (Ital. 'of Piero')

- the Leonardo family owned land in the village of Vinci near Florence for several generations, which they leased. The family therefore took the name da Vinci (Ital. 'from Vinci'). They were not noble

- "Messer" (Ital. 'My Lord') or "Ser" for short was an honorary title in Italy given to practicing lawyers. Leonardo's father Piero was a notary in Florence. "Lionardo di Ser Piero da Vinci" therefore means "Lionardo, son of the lawyer Piero from Vinci"

Probably when he finished his education, he called himself only Leonardo da Vinci. Like other Renaissance artists, such as Michelangelo or Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci is usually referred to only by his first name, Leonardo.

Leonardo da Vinci – Facts

| General information | |

|---|---|

| First name | Leonardo |

| last name | da Vinci |

| Initials | L D V (randomly the Roman numerals for 50, 500 and 5, added 555) |

| Birth name | Lionardo di Ser Piero da Vinci |

| Born | April 15, 1452 in a farmhouse near Vinci, Italy |

| Date of baptism | 16.04.1452 in the parish church of Santa Croce in Vinci, Italy |

| Asterisk | Aries |

| Nationality | Italian (Republic of Florence) |

| Epoque | Renaissance |

| Occupation | Painter, sculptor, architect, engineer, scientists |

| Teacher | Andrea del Verrocchio (Fine Arts) |

| Co-student | Sandro Botticelli, Lorenzo di Credi, Perugino |

| Deceased | 02.05.1519, at the age of 67 years |

| Place of death | at Cloux Castle in Amboise, France |

| burial site | Chapel in Clos Lucé Castle, France, exact location unknown |

| Family | |

|---|---|

| parents | illegitimate child of an affair of Ser Piero da Vinci (notary) with Caterina (peasant girl) |

| siblings | 17 half-brothers and -sisters (12 paternal, 5 maternal) |

| Marital status | unmarried |

| Descendants | none |

| Specifics | |

|---|---|

| Diet | Vegetarian |

| Handwriting | Left-handed; always wrote in mirror writing, presumably to avoid smudging the ink |

| Works | |

|---|---|

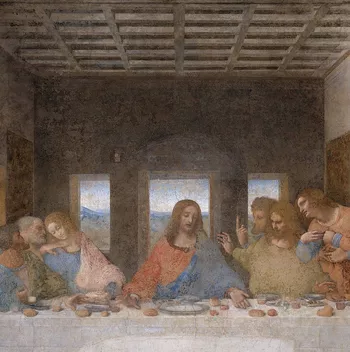

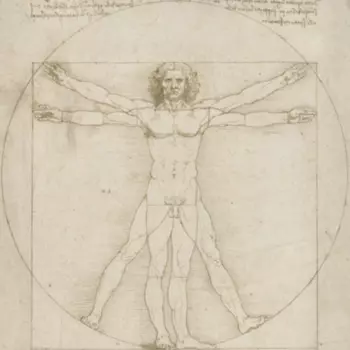

| Paintings | Virgin of the Rocks, Lady with an Ermine, Belle Ferroniere, Last Supper, Mona Lisa, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, John the Baptist, Vitruvian Man |

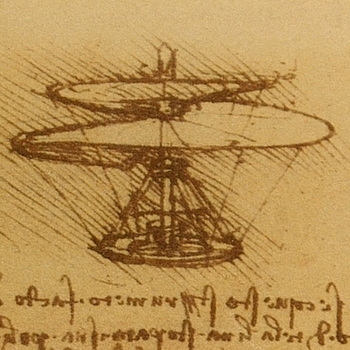

| Inventions | Aircraft, helicopter, parachute, automobile and mechanical robots with tension spring drive, tanks and much more |

| Writings | Book of painting, Codex on the flight of birds, Various scientific records ( Codex Atlanticus, Codex Leicester, etc.) |

| Pupils | Francesco Melzi, Jacopo da Pontormo, Andrea Solari, Bernardino Luini, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio |

| Knowledge | |

|---|---|

| Biology | Anatomy, Botany |

| Mathematics | Geometry, Arithmetic |

| Physics | Optics, astronomy, mechanics, mechanical engineering, hydraulics, fluid mechanics |

| Languages | Italian, Latin and French |

| Arts | Painting, sculpture, poetry, singing, various musical instruments |

| Time | |

|---|---|

| Events | Invention of printing, development of the heliocentric world view, discovery of America, Reformation |

| Contemporaries | Johannes Gutenberg, Nikolaus Kopernikus, Christopher Kolumbus, Martin Luther |

| Curriculum vitae | |

|---|---|

| 15.04.1452 | Birth in Vinci |

| 1452-1464 | Childhood on the farm of the grandfather in Vinci |

| 1464-1468 | Move to the father in Florence |

| 1468-1472 | Apprenticeship with Andrea del Verrocchio as painter, sculptor, architect and engineer, Florence |

| 1472 | Completion of training in the master's degree and admission to the painters' guild of Florence |

| 1472-1478 | Employed painter and engineer at Andrea del Verrocchio, Florence |

| 1478-1482 | Self-employed painter and engineer, Florence |

| 1482 | Move to Milan |

| 1482-1487 | Self-employed painter and engineer, Milan |

| 1487-1499 | Court artist and engineer to the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, Milan |

| 1500-1502 | Self-employed painter and engineer, Mantua, Venice, Florence |

| 1502-1503 | War engineer and cartographer for the commander of the papal army Cesare Borgia, Central Italy |

| 1503-1508 | Self-employed painter and engineer, Florence and Milan |

| 1508-1512 | Court artist and engineer to the French governor Charles II d'Amboise, Milan |

| 1513-1516 | Court artist and engineer of Pope Leo X, Rome |

| 1516-1519 | Court artist and engineer of the French King Francis I, Amboise |

| 02.05.1519 | Death in the castle of Cloux, Amboise |

How did Leonardo da Vinci live?

Leonardo was an illegitimate child. According to the custom of the time, he grew up with his father's family and spent his childhood in the idyllic village of Vinci. Leonardo's father, however, lived in Florence and hardly ever saw his son. It was not until he was a teenager that he took him in and had him trained as an artist in Florence. After tough early years, Leonardo's career did not begin until he was 30 years old. Then he left Florence for almost twenty years and set off for Milan. Leonardo became very wealthy and world famous there. In his later years he worked for the Pope in Rome and the French King. When Leonardo died in France, he was buried with the highest honors at the court of the French king. Almost nothing is known about Leonardo's private life. Although he was handsome and of good character, he remained unmarried and childless. Therefore, it is often claimed that Leonardo was homosexual.

Leonardo's painting

Leonardo created the Mona Lisa, the most expensive painting in the world (insurance value: 830 million euros). Although Leonardo is still considered the best painter of all time, he painted very few pictures. He did not sign his works and so it is very difficult to determine exactly which paintings were created by him. Around 1900, about 100 paintings were still attributed to Leonardo. However, through increasingly accurate research methods, Leonardo's works could be narrowed down to only 22 paintings today. It is very likely that there are actually even fewer, because even of these only seven are considered to be genuine without doubt. Five of these paintings are in the famous Louvre Museum in Paris. A small portrait, "Lady with an Ermine" is exhibited in Krakow, Poland. "The Last Supper" is a mural in a small church in Milan. The seven undoubtedly genuine paintings are presented here.

The universal genius

Leonardo da Vinci is today considered the epitome of the universal genius. His extensive technical understanding, combined with his scientific knowledge, led to numerous inventions and discoveries, some of which were centuries ahead of their time. Together with Luca Pacioli, one of the most influential mathematicians of his time, Leonardo worked on a book about proportions in nature. The drawing of the Vitruvian Man, which was probably created in this context, is world famous. In addition, Leonardo created the largest equestrian sculpture in the world at that time, but only as a plaster model in original size. Shortly before the final casting, the bronze needed for it was misappropriated for cannons, and the plaster model was destroyed in the war. In contrast, Leonardo's fables vividly testify to his vivid view of all things in nature.

Leonardo's experimental approach, which was to be guided only by experience and not by the ecclesiastical dogmas in force at the time, made Leonardo, even before Galileo Galilei, the founder of modern science. Leonardo also excelled in medicine. He was the first to dissect humans in order to produce detailed anatomical drawings. But not everything Leonardo aspired to succeeded. His lifelong dream of flying probably remained unfulfilled.

What is known today about Leonardo's ideas, constructions and thoughts comes from his surviving notebooks. The approximately 6,000 pages are called codices and are named after their former owners or current location. They are increasingly being digitized, translated, and made freely available online free of charge. A modern example of this is the digitization of the codex atlanticus of the milanese Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

Physics - The Founder of Modern Natural Science

Leonardo's work and his writings had a decisive influence on the natural scientists who followed him. Until the modern age, no great name can be found that has not dealt with Leonardo's ideas. This is due to the fact that Leonardo researched in every field and then was often the first to question everyday things.

His scientific method was revolutionary because he investigated methodically. If he noticed something, he thought about the cause, came to an explanation and then tried to prove the assumption in the experiment. He proceeded very conscientiously and tried to derive general laws from the experiments. However, he was not free of errors, for example, when he claimed that at the bottom of the sea the water was sweet. How modern Leonardo's findings were is shown by his understanding of cosmology. Leonardo assumed quite naturally that the sun was the center of our planetary system. He notes only succinctly, "The sun does not move."

Leonardo's influence on Galileo

Galileo Galilei worked about 100 years after Leonardo and lived in Florence, Leonardo's hometown, from the age of 46. Galileo's legendary impact on science is undisputed, but in detail it reads like a continuation of Leonardo's work, almost as if he had thematically taken his cue directly from Leonardo's writings. Some examples:

Galileo's method of exploring nature through a combination of experiments, measurements, and mathematical analysis goes back to Leonardo, who applied the principle 100 years before him

Galileo's investigations of free fall and the action of forces are continuations of experiments conducted by Leonardo in Rome (1513-1516)

It is the same with Galileo's optical experiments. Telescopes for observing the heavens were not invented until the early 1600s. However, Leonardo planned to build the first reflecting telescope (concave mirror) in Rome as early as 1513 with the help of German mirror makers. It was to be several meters in diameter and serve for celestial observation. However, in letters to the pope's brother, Leonardo complained that the German mirror makers were not doing their job. Leonardo left the Pope's court in Rome after only three years, and the massive telescope remained unfinished. The technical plan for the manufacture of the apparatus has been preserved

Galileo is known, among other things, for the study of the flow behavior of liquids. Again, Leonardo was the first since antiquity to study the subject and left numerous reflections on it

These are only a few examples of many that clearly show Leonardo's influence on the history of modern physics.

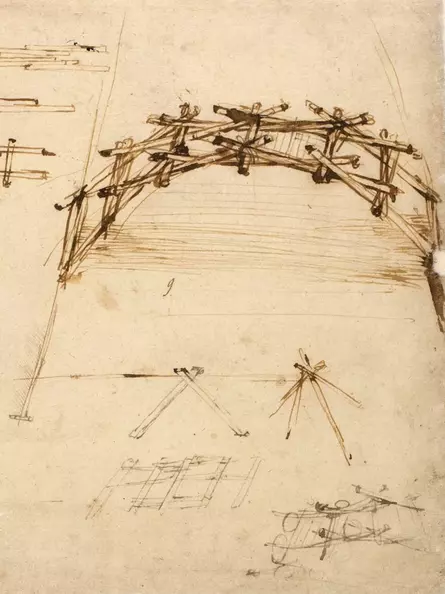

Mechanics: The bridge is self-supporting and consists of individual loose logs, which only need to be placed on top of each other in this way, ropes or nails are not necessary

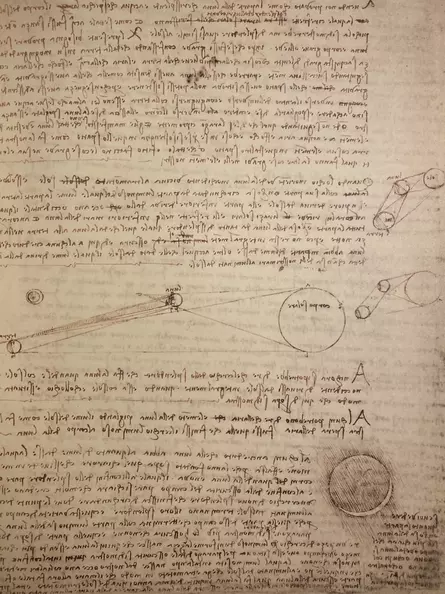

Optics: At this point Leonardo explains that at new moon the earth-facing side of the moon reflects the sunlight that hits the earth. Therefore the actually dark new moon appears in a pale light

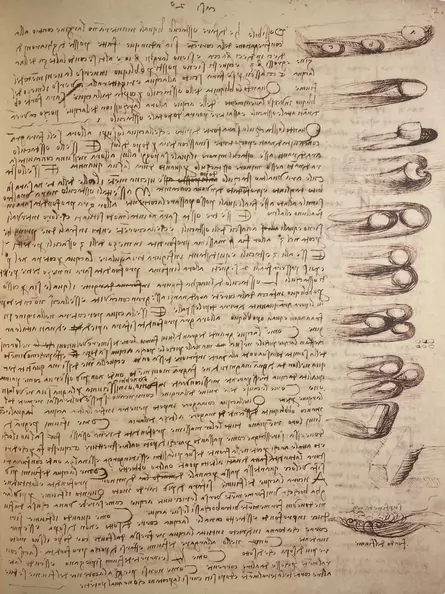

Fluid mechanics: Here Leonardo explains how to prevent the undercutting of sections of shoreline by altering the current

The sun does not move

Biology - The first anatomical drawings

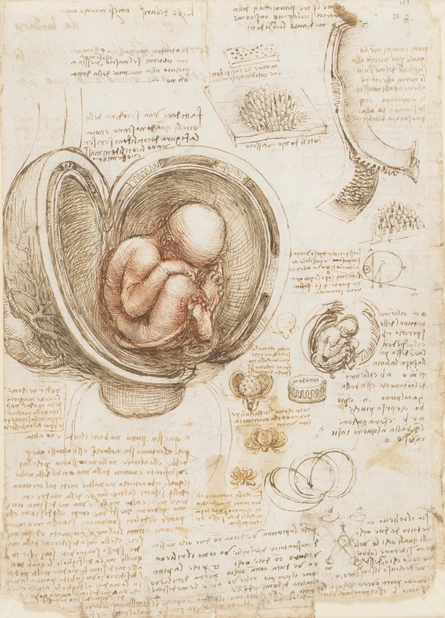

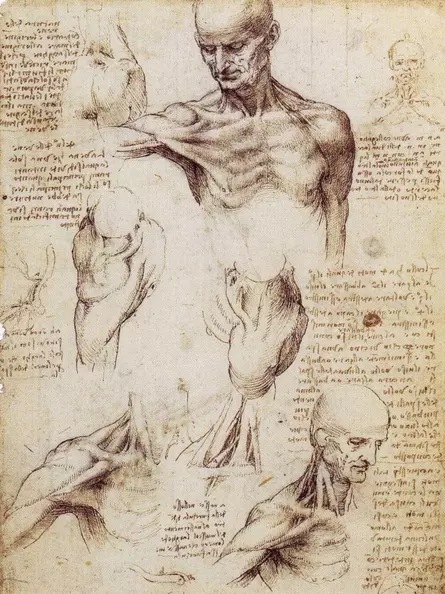

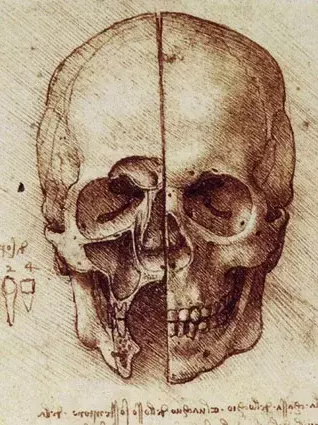

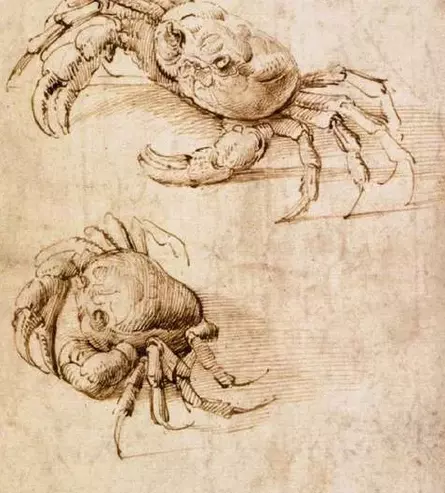

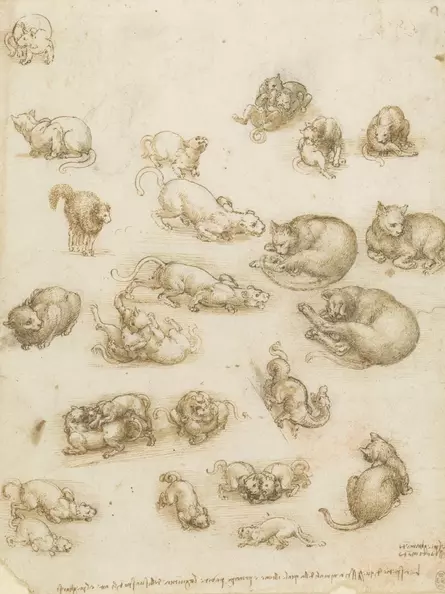

Leonardo was the first to make anatomically correct drawings of humans and animals. According to his own statement, he dissected about 30 people for this purpose. This was probably done secretly, because at the end of the 15th century it was forbidden to open corpses due to church dogmas, but there were exceptions. For example, dissections were allowed at medical colleges. However, they were rarely performed, but then they were a special event for the students.

Together with Marcantonio della Torre, a professor of medicine who taught at the University of Padua, Leonardo planned a book on human anatomy. The book was not published because the professor died of the plague at a young age (1511). Many of the anatomical drawings from this period have been preserved. Leonardo was the first to compare the anatomy of animals and humans, noting their similarities.

Leonardo's anatomical sketches are not always free of errors. For example, one depiction of the sexual act shows a direct connection between the nipple and the uterus. Whether such cases were really errors on the part of Leonardo, who was always very precise, or whether they were knowing jokes remains unclear. Leonardo never separated between science and art.

The surrounding uterus is not human, but that of a cow. Whether it is one of Leonardo's typical jokes or he improvised in the absence of a model is unclear.

Mathematics - The Aesthetics of Geometry

Common to all of Leonardo's paintings is the hidden language of geometry. Leonardo constructed his paintings on the basis of geometric proportions, shapes and patterns, which have their origin in the ancient art of geometry. Leonardo assumed that everything in nature, i.e. the cosmos and atoms could be traced back to the simplest proportions and he investigated these relationships.

Luca Pacioli and Leonardo da Vinci

Around 1498, Luca Pacioli, an important mathematician at the time, was invited to Milan by the Duke of Milan. Leonardo was working at the court of Milan at the same time, and this is how he met Luca Pacioli. They began to work on joint projects.

The boundaries between art and science were fluid at the time. This was also true for Luca Pacioli. Luca Pacioli was a student of the exceptional painter Piero della Francesca. Della Francesca introduced central perspective into painting at the same time as the painter Masaccio. He also wrote numerous mathematical treatises on geometry. This work was continued by his pupil Pacioli. Still significant today is Pacioli's book on double-entry bookkeeping, which is the first complete summary of this method. In addition, he wrote a lost book on chess, which is said to have been illustrated by Leonardo. He also wrote a summary of the algebra known at that time.

"Divina Proportione" (Divine Harmony)

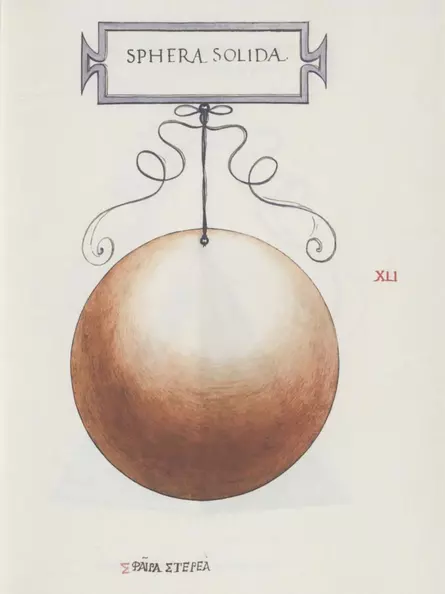

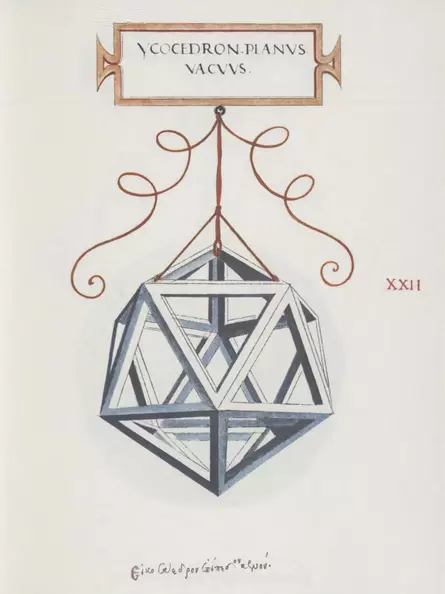

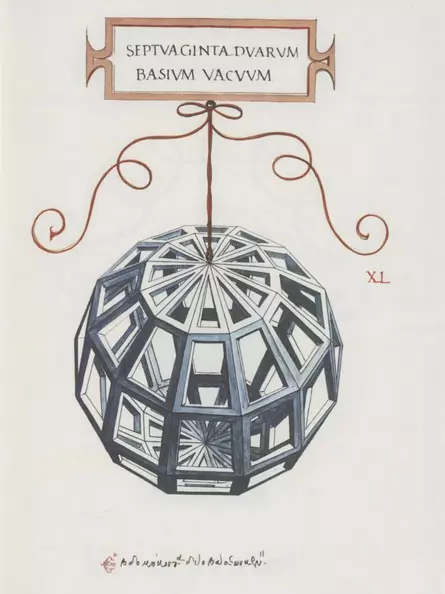

When Pacioli wanted to publish his influential book "Divina Proportione" (Divine Harmony) in 1498, he asked Leonardo to do the illustrations for it. Leonardo drew a total of 60 geometric figures for the manuscript of the book, which essentially deals with geometric proportions, such as the golden ratio, and their applications. Pacioli also explores in this book the teachings of the ancient master builder Vitruvius, after whom Leonardo's Vitruvian Man is named. It also contained a mathematical essay by his now-deceased teacher Piero della Francesca.

A total of three manuscripts of the book were made as particularly beautiful specimen copies for noble donors, one of which went to the Duke of Milan. The third is considered lost. The remaining two books are in Milan and Geneva. The illustrations below are from the Milan version, which is considered better preserved overall. The back cover, also painted, is to be seen through. For the printed editions of the book, the plates were no longer handmade, but printed according to Leonardo's model.

The sphere is the only one of the 60 illustrations that is not a polyhedron. Polyhedra are three-dimensional objects bounded exclusively by plane surfaces

The illustrations are the first representations of geometric figures in skeleton structure. The vividness of the objects is thus significantly increased.

This polyhedron is reminiscent of today's earth's grid of degrees

The mathematical joke of Leonardo

Leonardo has introduced an error in the numbering of the plates. In the table of contents of the plates the following numbering is shown with Roman numerals:

41 (The Sphere), 1, 2, 3,..., 39, 40(Septuaginta Duarum), 43, 44,..., 60, 61.

The numbering goes up to 61, but only 60 plates are shown. Plate 42 is missing.

The reason for this is that the sphere, the only figure of the plates that is not a polyhedron, is listed first in the table of contents, but is labeled as plate 41. In the table of contents, the 40 is followed by the 43, but actually the 42 should follow, because the 41 with the sphere is already listed in the first place. The wrong numbering then continues to 61, so that 61 is counted, although there are only 60 plates in total.

An accidental mistake?

It can be assumed that neither the mathematician Pacioli nor the very thorough Leonardo would have failed to notice the error. It is therefore probably one of Leonardo's typical jokes.

First hint: The penultimate polyhedron, which is still numbered correctly, is the Septuaginta Duarum with 72 faces (right figure). Pacioli's book puts the golden section in the foreground. The symbolic 72° angle is the center angle of the regular pentagon, which can only be constructed with knowledge of the golden section.

Second hint: The penultimate plate 40 with the 72-faced figure is followed by the last correctly numbered plate 41 with the sphere. The similarity of the two figures is not accidental. Geometry is the ancient Greek word for 'measurement of the earth' (geo 'earth', metron 'measure'). The earth is measured by covering it with a grid. For an interpretation of the plate 41, thus the sphere as earth, speaks likewise the point at which the sphere was hung up. The angle can be calculated over the (co)sine and corresponds to approx. 23°, thus the inclination of the earth axis. The suspension point is different for the figures.

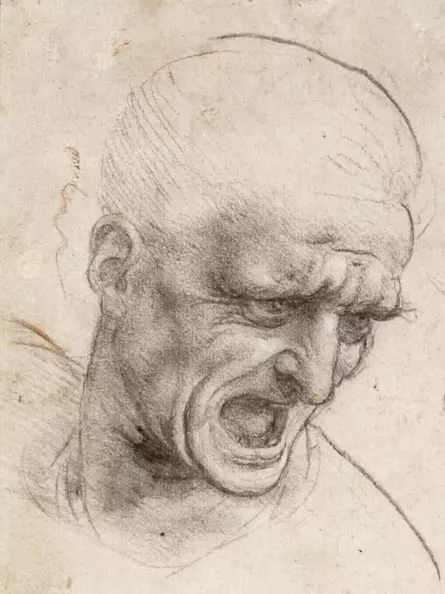

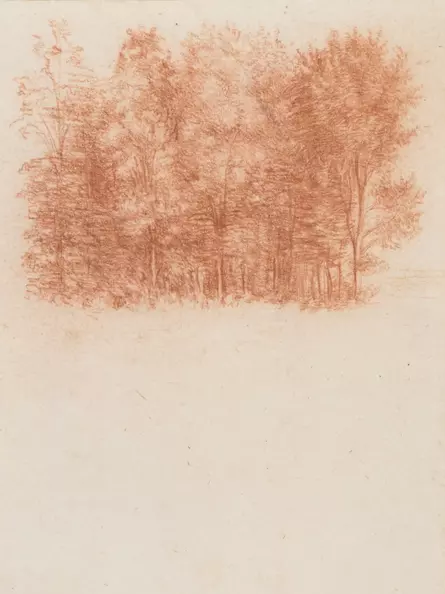

Art - Nature in view

Leonardo was a gifted draftsman. His drawings from nature are considered the most beautiful in the history of art. He was the first to put nature in the foreground of his observation. Leonardo refused to copy the works of others in the studio, as was customary at the time. He always drew from models from the real world. One source reports that he never left the house without a notebook.

This drawing is the first known drawing in the history of art that exclusively shows a landscape. Until then, it was common to show the landscape only as an accessory to portraits or religious scenes. It is remarkable that this landscape does not exist in reality like this, but parts of it do. Leonardo has thus condensed various views of his homeland into one image. This drawing is also the first datable work of Leonardo, he was 21 years old. The sheet is inscribed in mirror image on the upper left with "Day of St. Mary in the Snow, on the day August 5, 1473". At the bottom right it is signed "Leonardo" in normal writing direction

This drawing is considered a study for the painting "Virgin of the Rocks"

This drawing is considered to be a study of the lost painting "Leda with the Swan".

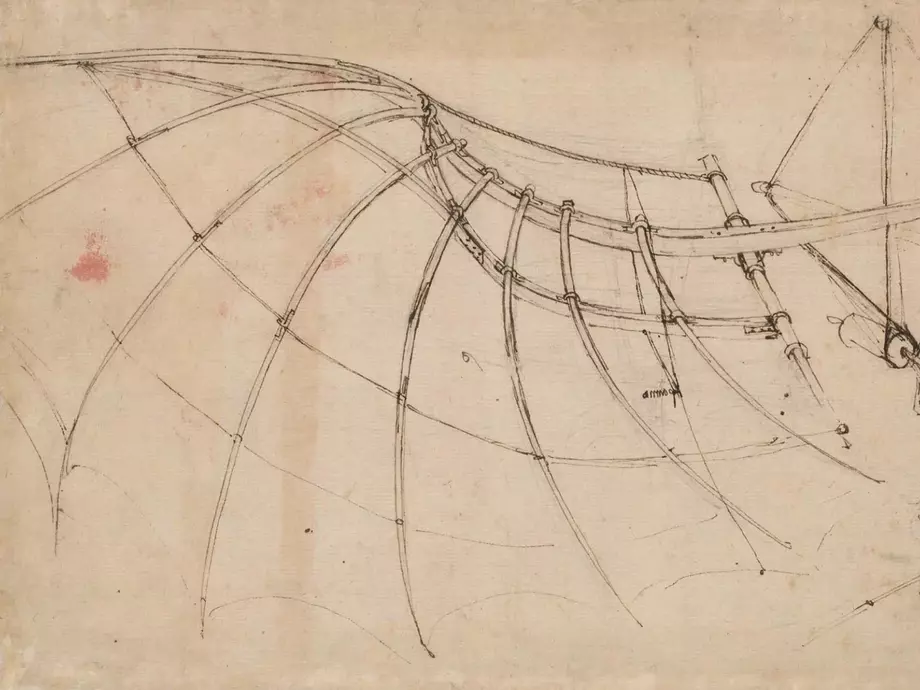

Leonardo's attempts at flight

Leonardo spent his life developing a flying machine. For this purpose, he studied the flight of birds and wrote the Codex on the Flight of Birds (Codex Turin).

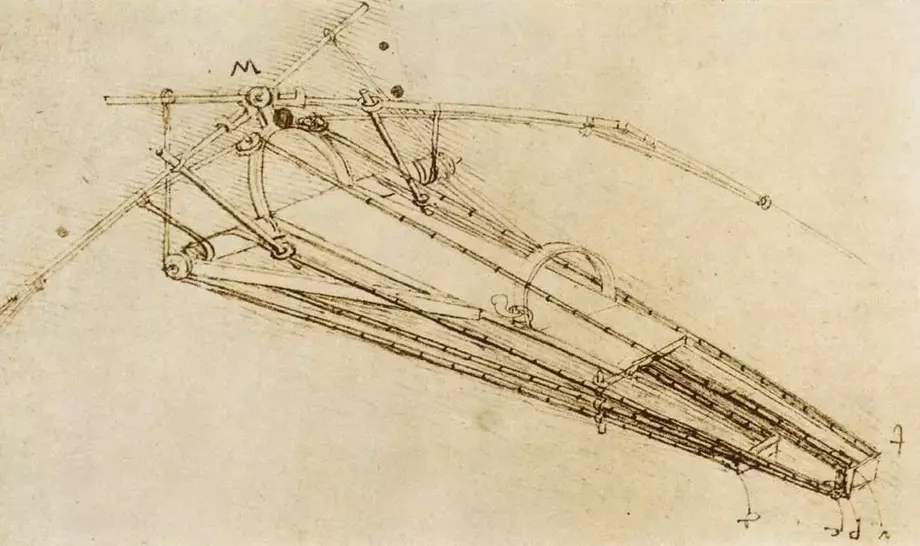

Development of flying machines

He first tried to build a flying machine that would allow people to move wings with mere muscle power. When he realized that this could not succeed because of the dead weight, the huge size of the wings, and the force and frequency of wingbeat required, he began to develop models for gliders instead. The gliders had elevators and rudders, so they were maneuverable. The glider was designed for one person lying in a horizontal capsule centered under the wing. So very similar to today's hang gliders.

Flight experiments

There were also flight experiments. Leonardo made a strikingly pathetic note around 1505: "For the first time the great bird will soar, from the back of the mighty swan, filling the whole world with wonder and all the scriptures with its glorious deed, to the eternal glory of the nest where it was born." By the "back of the mighty swan" is meant the Swan Mountain ('Monte Ceceri'), a hill near Florence where Leonardo stayed around 1505. The hill slopes very steeply to one side, making it ideal for launching a glider. Today there is a memorial stone there in memory of Leonardo's attempts.

However: The attempts probably failed. His long-time collaborator Tommaso Masini, a specialist in metals, broke some bones, as Leonardo noted in one of his notebooks. The reason for the failure may have been incorrectly fastened materials. It is unclear whether further (successful) flight attempts were made. If the attempts were successful, Leonardo would have been the first designer of a glider 300 years before Otto Lilienthal.

Other flying machines

Leonardo also designed a parachute, which was successfully tested in June 2000. Likewise, Leonardo designed a helicopter (propeller), but it had too weak a propulsion system to take off.

The wings should be covered with leather and worked linen

The pilot's cabin. The feet were located at the bottom right. The wings could be moved independently via winches

Short biography

Origin, childhood and education

In 1452 Leonardo was born Lionardo di ser Piero (father's name) da Vinci (birthplace). He was the illegitimate child of an affair of the notary Ser Piero with Caterina, a peasant girl. There are various theories about the identity of Leonardo's mother. They separated shortly after Leonardo's birth, probably because of the difference in status.

Leonardo remained with his father, which was common for illegitimate children at the time. His mother soon married a wealthy local farmer and had four more children. Leonardo probably grew up with his grandparents in Vinci. His mother lived only a few miles away, so it seems possible that Leonardo could have visited her. Illegitimate children were not legally equal to legitimate offspring, which put Leonardo at a disadvantage compared to his 12 legitimate paternal siblings, presumably not only in matters of inheritance.

It is unknown where or if he went to school. Certainly he learned to read, write and calculate. In 1464, when he was 12 years old, his grandfather died. Presumably he then moved in with his father in Florence. He must have had a talent for drawing, since he completed an apprenticeship as an artist in the workshop of the Florentine Andrea del Verrocchio. The latter was a well-known artist throughout Europe in his day, excelling especially in painting, sculpture and architecture. Leonardo was there a fellow student of the later also very famous painter Sandro Botticelli. Leonardo's father, who came from an old-established Florentine notary family and also worked as a notary, could have taught him. He worked, among other things, for the city government of Florence and the famous Medici banking family, so he must have had a high social status and financial means.

In 1472, at the age of 20, Leonardo was admitted to the painters' guild "Compagnia di S. Luca". Although this meant that he could have worked as an independent painter, he probably worked with or for Verrocchio for another ten years (until 1482 at the latest). No independent works from this period are known. He is believed to have worked on two paintings from Verrochio's workshop, "The Baptism of Christ" and "Annunciation to Mary." The attributions are highly controversial among art historians, however, as it is unclear exactly what Leonardo's contribution was supposed to have been.

Self-employed painter in Florence

In 1478, at the age of 26, Leonardo began to seek his own commissions. There was no shortage of great artists in Florence at that time. Competition was fierce, and commissions were difficult. The few commissions Leonardo received were probably through his father. Probably the first commission is the unfinished painting "St. Jerome". Apart from the fact that the painting is attributed to Leonardo, however, nothing is known about it. It shows the consistent effort of an anatomically correct representation of a male nude torso.

This suggests that Leonardo was already conducting anatomical studies in Florence. This was a risky undertaking, since dissecting cadavers was forbidden in the ecclesiastical context of the time and was considered heresy. Only medical universities were allowed to conduct such studies on a very limited scale. Although the majority of the Renaissance is now considered enlightened and liberal, the fragility of the concept of a liberal society in northern Italy and the deep-rootedness of ecclesiastical dogmas are shown by the political influence of the priest Savonarola, who transformed Florence into a divine state of religious zealots from 1494 to 1498.

In this tension between ecclesiastical dogma and liberal sentiment, Leonardo was anonymously accused in 1476 of homosexual intercourse with a prostitute known to the city. This was a fatal charge and could have meant Leonardo's execution. A public trial began, during which well-known Florentines testified on his behalf as character witnesses, including his teacher Verrocchio. Together they were able to help Leonardo to an acquittal. The charges, the public trial, and the threat of an early death must have had a shocking effect on the 26-year-old Leonardo.

For the church of San Donato a Scopeto just outside Florence, he received another commission around 1478. He was to create an altarpiece with the motif "Adoration of the Magi". This painting also remained unfinished, presumably because he saw for himself a chance for employment at the court of the powerful Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza. Milan at that time was the fifth largest city in Europe with 100,000 inhabitants and already at that time a famous metropolis.

Departure to Milan

The Duke of Milan was looking for a capable artist to design and execute his long-planned prestigious project of a monumental equestrian statue. Leonardo da Vinci made great efforts for this commission. His letter to the duke in 1482 became famous, in which he recommends himself to the warlike ruler as a technician and engineer of war equipment. Almost in passing, he also mentions his sculptural and painterly talent at the end.

Self-employed painter in Milan

Leonardo's efforts to obtain employment at the court of Duke Ludovico Sforza were initially unsuccessful. Nevertheless, he left his native Florence and settled in Milan. There, in 1482, he was commissioned, along with two other painters, to create a large altarpiece for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception in the Franciscan Church of San Francesco in Milan. Leonardo's contribution was the central image of the altar, the Virgin of the Rocks.

The painting was of groundbreaking elegance for the time and was considered so extraordinarily beautiful that other interested parties quickly found it. Therefore, shortly after completion, instead of delivering it to the monks as intended, it was sold to a private individual for a much higher bid. A decades-long legal dispute with the monks followed, which finally led to a second version of the "Rock Grotto Madonna" being made around 1508, 26 years later, which the monks received as compensation.

In the service of the Duke of Milan

In 1487, possibly before, Leonardo's efforts to obtain a position at the court of the Duke of Milan were finally successful. The duke sought in Leonardo not only an artist, but also a court engineer and inventor who would assist him in times of peace as well as war.

Years of wandering

Leonardo da Vinci spent almost 20 years in Milan, at least 12 of them in the Duke's service.

In 1499, when Leonardo was 47 years old, the Duchy of Milan was occupied by the French, and the Duke of Milan fled. Leonardo thus lost his patron. He continued to receive payments from French patrons, but left Milan.

Little is known about the period that followed. It is believed that he moved through the duchies and republics of northern Italy in search of new patrons. He is said to have spent over 1-2 years in Rome, Naples, Mantua and Venice before finally returning to Florence.

Here, in 1502, he entered the service of Cesare Borgia, the pope's son and commander of the papal army. He accompanied the latter, probably for a year, in his campaigns and travels, assisting him in the planning of fortresses, town planning and the drawing of maps.

In 1503 Leonardo was commissioned by the Florentine municipal government to paint "The Battle of Anghiari". The mural was planned for the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of the Florentine Parliament, and was intended to commemorate a great military victory for the Republic of Florence. This commission was probably designed as an artist's competition, because Michelangelo, also a very famous artist, was also commissioned to paint in the same hall, on the opposite wall, a painting of another important battle, the "Battle of Cascina". Both works were accompanied by considerable technical problems due to wall wetness and were not completed. Today, only preparatory studies of them have survived. Legendary is the dislike that the two artists are said to have felt for each other.

Leonardo also began work on the "MONA LISA" at this time. It is still unclear today on whose behalf he made the painting.

He then experienced the death of his father in 1504, who died in Florence not far from the Palazzo Vecchio, as Leonardo notes in his notes. As a result, a dispute arose over the inheritance and Leonardo, as an illegitimate son, came away empty-handed. This probably affected him, because when Francesco, his father's brother, died in 1507, Leonardo used his international political influence on the Florentine city government to assert his claim to the inheritance over his siblings.

Return to Milan

In 1506 Leonardo returned to Milan at the request of the French governor Charles II d'Amboise, and subsequently commuted between Florence and Milan. He intensified his anatomical studies and worked closely with the medical faculty of the University of Pavia.

The professor there, Marcantonio della Torre, dissected and Leonardo made drawings of them. Both planned to publish a book on anatomy. However, this project was thwarted by the early death of the professor. The resulting drawings and the anatomical knowledge gained from them represent another significant achievement in the life of Leonardo da Vinci.

In 1508 at the latest, Leonardo stopped commuting between Florence and Milan and settled back in Milan. Here he began work on his painting "Anna Selbdritt". For the French governor of Milan, Charles II d'Amboise, he was now active as an architect, engineer and court artist, as he had been for his predecessor, the Duke of Milan. Once again, he was to construct a massive equestrian monument for the Frenchman.

The statue was planned on the occasion of the victory of the French over the Duchy of Milan and was to show the victorious army commander Gian Giacomo Trivulzio. Before the planning was completed, the Sforzas were able to retake the Duchy of Milan in 1512. Ludovico Sforza, the former Duke of Milan, was in prison in France, but his son now succeeded him. The latter did not want to continue supporting Leonardo as a patron.

Leonardo remained for some time in the house of his noble and wealthy Milanese student Francesco Melzi. He then left Milan for good, however, when he followed the Medici family's call to Rome.

Stay in Rome

The influential Florentine banker family Medici provided at this time with Leo X. the pope. His brother Giuliano di Lorenzo de' Medici was an outstanding patron of the arts and had already been able to bring Michelangelo and Raphael to Rome. Michelangelo then painted, among other things, the Sistine Chapel and rebuilt St. Peter's Basilica, while Raphael painted the Pope's private rooms (Raphael's Stanzas).

What Leonardo accomplished in Rome during this period is not known in detail. He probably began work there on his last painting, "John the Baptist". It is further assumed that he was involved in draining the Pontine marshes. He also conducted numerous experiments in physics, including the inclined plane, to study the effect of forces in free fall. Several letters to Giuliano are also known, in which he complains about the laziness of traveled German mirror makers who were to assist him in the manufacture of a concave mirror for astronomical observation. It is not known whether the telescope could be built despite the difficulties. Leonardo also investigated methods of applying and preserving oil paints more intensively than ever before.

Amboise - At the French court

After three years at the papal court, Leonardo receives an invitation from the French King Francis I in 1516.

He leaves Rome and lives the last three years of his life at the castle of Clos Lucé near Amboise in northern France. The castle of Amboise was the headquarters of the French king at that time. It was located only 500m away from Leonardo's castle. The two were connected by a tunnel. The king is said to have used it for inconspicuous conversations with Leonardo. Leonardo reworked the "Mona Lisa", the "Anna Selbdritt" as well as "John the Baptist" here.

In addition, he acted as a technical advisor, once again designed an equestrian statue that was not realized, and acted as a creative mind for fantastic ideas on public occasions. Furthermore, he took care of a sewerage project in Sologne and the work on a royal palace in Romorantin.

Leonardo's death

Leonardo died on 02.05.1519 in his castle Clos Lucé. Nothing is known about the cause of death.

The travel report of a visitor of Leonardo in his last year of life is interpreted to the effect that Leonardo should have had a series of strokes.

According to this report, Leonardo was paralyzed on the right side and therefore could only use his left hand. His overall condition is said to have already appeared very frail. The paralysis is often used as an argument for a suspected stroke, but Leonardo was left-handed and could therefore have preferred to use his left hand.

The biographer Vasari reports of the day of Leonardo's death that he asked forgiveness for his sins against God on his deathbed and then died in the arms of the French King Francis I. It is unclear whether Leonardo was a left-handed artist. It is unclear whether the narrative is true. What is true is that Vasari wrote down two versions in different editions. Only in the second version, written after the Counter-Reformation, does he have Leonardo ask forgiveness for his sins against God. The Counter-Reformation led to an eager return to the Catholic faith after the Reformation by Martin Luther. It is possible that Vasari made his adaptation under this impression.

Leonardo's funeral ceremony

Leonardo's death was not unexpected, as he had made his will a few weeks earlier. There Leonardo da Vinci determined the order of his funeral.

- Leonardo wanted to be buried in the church of Saint-Florentin in Amboise. The church is named after Saint Florentin. The name Florentin is derived from the Latin verb florens ('blooming'), as is the name of Leonardo's hometown of Florence, 'the blooming one'. The coat of arms of Florence is a blooming lily

- three solemn and thirty silent masses are to be held in the four churches of the royal seat of Amboise before the funeral

- Leonardo's coffin will then be carried from the castle of Cloux to the church of Saint-Florentin by the chaplains of this church

- the coffin shall be accompanied by sixty paupers, each carrying a large candle, and by the rector or prior of the church of Saint-Florentin or its delegates and dignitaries of the three other churches

- the sixty candles are then to be distributed equally among the four churches of the village, that is, 15 candles per church

Leonardo was buried in the cemetery of the church of Saint-Florentin in the park of the castle of Amboise. The tomb was destroyed between 1562 and 1598 and during the Napoleonic period around 1807, Leonardo's remains have since been considered lost.

His works of art and paintings subsequently became the property of the French king. His manuscripts and equipment were in the possession of his long-time student and executor, the noble painter Francesco Melzi. Leonardo's possessions went to his servants, pupils and siblings.

Sources

Frank Zöllner, Leonardo, Taschen (2019)

Martin Kemp, Leonardo, C.H. Beck (2008)

Charles Niccholl, Leonardo da Vinci: Die Biographie, Fischer (2019)

Especially recommended

Marianne Schneider, Das große Leonardo Buch – Sein Leben und Werk in Zeugnissen, Selbstzeugnissen und Dokumenten, Schirmer/ Mosel (2019)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/7/0/csm_anna-selbdritt_370c8646a0.webp.pagespeed.ce.NuSK1feNeY.webp)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/1/2/csm_war-leonardo-da-vinci-schwul_194272ff8d.webp.pagespeed.ce.IG-OHSWppt.webp)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/b/csm_leonardo-alle-gemaelde_2dc4b01ef6.webp.pagespeed.ce.ohfmgl8OfF.webp)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/1/2/csm_cavallo-leonardo_bf668e6f21.webp.pagespeed.ce.ZaoNyB4ZGh.webp)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/0/7/csm_leonardos-fabeln_9df3358564.webp.pagespeed.ce.Mi4Wo6pyru.webp)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/7/csm_leonardos-bewerbungsbrief-an-den-ludovico-sforza_738f5e65d2.webp.pagespeed.ce.vkwc8_RyDP.webp)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/c/e/csm_paolo-giovio_0acfba0bba.webp.pagespeed.ce.jz7fnLT_Al.webp)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/2/8/csm_sigmund-freud-kindheitserinnerung-des-leonardo-da-vinci_413da547be.webp.pagespeed.ce.6JdSEa4Rkx.webp)