An ermine kills a rabbit (from 2:37)

Lady with an Ermine

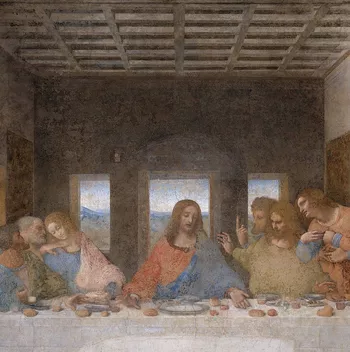

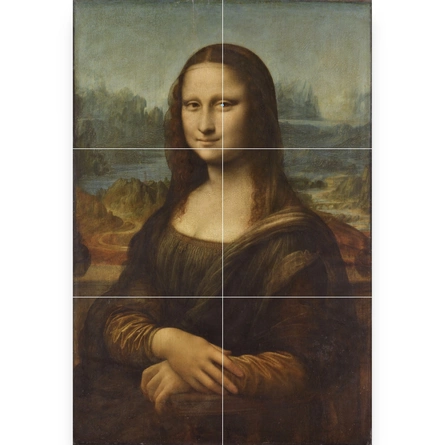

The Lady with an Ermine is a painting by Leonardo da Vinci, painted in Milan around 1490. It depicts a mistress of the Duke of Milan Ludovico Sforza, Cecilia Gallerani. She is holding a white ermine in her arms, the duke's heraldic animal. The portrait is now in the Czartoryski Muzeum in the Polish city of Krakow.

Do not reveal, if freedom is dear to you, that my face is a prison of love.

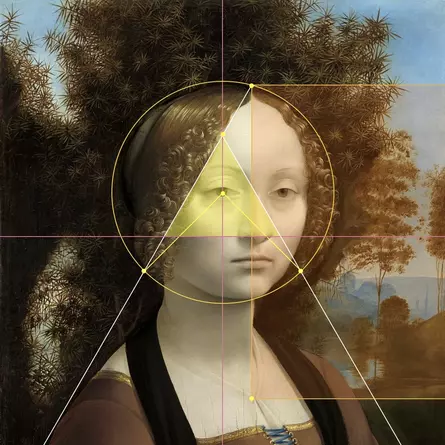

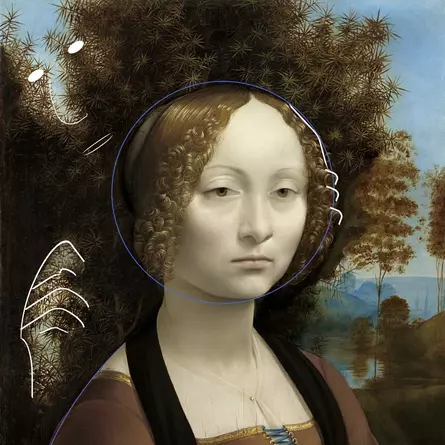

Leonardo da Vinci's paintings cannot be understood without examining the geometry of the picture

Leonardo da Vinci

around 1490

Oil on wood (walnut)

39 x 53cm

Czartoryski Muzeum, Krakow, Poland

Insurance value: 350 million euros

Who was Cecilia Gallerani?

Cecilia Gallerani is the lady with the ermine.

Cecilia's family

Cecilia Gallerani was born in Milan in 1473. Her father Fazio was an ambassador for the Italian small states, among others for the republics of Florence and Lucca. However, he died very early, when Cecilia was 7 years old. Her mother Margherita Busti was the daughter of a jurist. The couple had six sons besides Cecilia.

Noble marriage policy

In 1483, at the age of ten, she was betrothed to Giovanni Stefano Visconti. The engagement was broken off in 1487 for unknown reasons.

In early 1489, the 37-year-old Duke of Milan Ludovico Sforza made Cecilia, who was only sixteen years old, his mistress. Cecilia then moved into a rural estate in the parish of Nuovo Monasterio. The duke openly supported her and her family. When her brother Sigerio killed a man in a quarrel in 1489 and was to be executed, Ludovico's personal intervention prevented this. Moreover, Cecilia's affair with the Duke of Milan certainly brought further benefits to her family. Finally, in the summer of 1490, Cecilia became pregnant. It was around this time that Leonardo da Vinci completed the painting.

Relationship of three

The duke's affair was politically sensitive, since Ludovico had already been engaged to Beatrice d'Este (b. 1475), then only five years old, since 1480. She was the daughter of the influential Duke of Ferrara. The marriage took place regardless of the simultaneous pregnancy of Cecilia on 16.01.1491, although the affair of the duke was an open secret. Beatrice d'Este refused to sleep with the Duke as long as he kept a mistress. She gave him an ultimatum and demanded that the affair end. Only a few months after the wedding, on 03.05.1491, Cecilia gave birth to a son, Cesare Sforza, to the Duke.

Even before the birth of the son, Ludovico followed the insistence of his wife Beatrice and he ended the affair. Cecilia had left the court by the end of March 1491. However, the duke remained attached to the mother of his son and continued to support her. He appointed her a husband. The choice fell on Count Ludovico Carminati de Brambilla, called Bergamini, whom she married in 1492. The duke subsequently provided her with the magnificent Palazzo Carmagnola in Milan and a fief in Saronno, so that Cecilia could live the life of a noble lady as the wife of a count. The couple had four children.

Cecilia

Cecilia must have been very beautiful, her beauty was the subject of numerous contemporary letters and poems.

She was considered clever and very educated. She spoke fluent Latin, played music, wrote poetry and was a pleasant entertainer. Among other things, she was known for inviting people to salons. There she discussed questions of religion, art and philosophy with high-ranking personalities. Her salons were probably the first of their kind in Europe. She was also active as a patron of writers, such as the novellist Matteo Bandello.

Cecilia's former lover, the Duke of Milan was expelled from Milan by the French in 1499, stripped of his power, and died in French captivity in 1508. Their mutual son Cesare pursued an ecclesiastical career, became an abbot, but died at a young age in 1512. Cecilia's husband Ludovico Carminati de Brambilla probably died around 1514, and the fate of their four children together is unknown. Cecilia Gallerani died in 1536 at the age of 63 at her castle in San Giovanni in Croce, about 100km southeast of Milan. The painting was in her possession until her death.

Symbolism of ermine

The ermine that gives the title was not chosen at random. It is a very symbolic animal, especially for the high nobility to this day. It also refers to Cecilia's surname and her pregnancy at the time the painting was created.

Word play with the surname Cecilias

The ancient Greek word for weasel - the ermine is one of the weasels - is galê or galéē and can thus be understood as an allusion to Cecilia's surname, Gallerani. Leonardo da Vinci and his patrons had a penchant for puns, they were a fashion of the time.

Protective animal of pregnant women

The mistress Ceciila Gallerani became pregnant by the Duke while the painting was being made. It is therefore worth noting that the ermine has been the guardian animal of pregnant women since ancient times.

This is due to a legend surrounding the birth of the ancient hero Hercules. The famous Roman poet Ovid (43 BC - 17 AD) tells about it in his main work, the "Metamorphoses".

The ancient legend

Zeus, the father of the gods, impregnated the earthly Alcmene by masquerading as her husband.

His ever-jealous wife Hera took revenge on Alcmene by instructing the goddess of birth, Eileithyia, to squat on her altar and cross her knees so tightly with her arms that this spell would prevent Alcmene from giving birth. After Alkmene had been in labor for seven days and seven nights, her maid Galanthis could no longer bear Alkmene's pain and told the goddess of birth, Eileithyia, to congratulate Alkmene, who had just given birth to a boy. The deceived Eileithyia jumped up in horror, her legs were now no longer crossed and the spell was broken.

Alcmene delivered her son Heracles. The maid Galanthis, laughing loudly because of the successful trick, was shortly after thrown to the ground by the goddess Eileithyia and turned into an ermine as punishment. According to ancient belief, the transformed maiden was now condemned to bear her children through the lying mouth with which she had helped Heracles into the world.

The tradition of the legend

Since then, in Greek educated circles, the ermine was considered the guardian animal of pregnant women and was supposed to give pregnant women the safest possible delivery. If a woman was in labor, she was handed wet cloths from a bowl with ermine motifs. Wearing an ermine skin on the bare skin was also supposed to protect the woman from the dangers of childbirth.

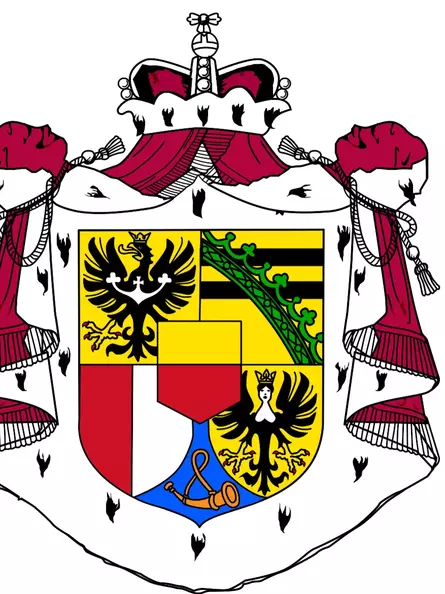

Symbol of the high nobility

The ermine has always been considered a symbol of wealth and power. The ceremonial cloak of emperors, kings, dukes and cardinals is always a cloak made of the white winter fur of the ermine with the characteristic attached black tail tips. This cloak still adorns all the coats of arms of the European high nobility.

Why does the nobility identify with the ermine?

The classical task of the nobility was threefold.

- to be a moral example, i.e. the proverbial chivalrous behavior (nobility)

- provide for offspring to secure the dynasty (fertility)

- take over the military defense in times of war (fighting spirit)

The ermine symbolically combines all three qualities.

Nobility: the ermine has a white winter coat

Ermines have a brown coat with white underside in summer. In winter, however, they are completely white. The tip of the tail always remains black.

Fertility: The stoat is very fertile

Ermines live only 1-2 years in the wild. But they are very fertile, so already the young animals can be impregnated. Up to 18 young animals are born per litter. Ermines therefore reproduce very quickly.

Fighting spirit: The stoat is muscular, agile and combative

Ermines have a muscular body shape and yet move very elegantly. The stoat is very aggressive and defends its territory aggressively. It does not shy away from fighting dangerous snakes or much larger animals.

The expensive coats from ermine fur

Since the fluffy coats made from the fur of the ermine were very expensive, only the high nobility could afford them. A typical feature of these coats is the addition of the black tail tips of the ermine. Ermine coats became an insignia of the nobility's power from the 14th century. At times, non-nobles were even forbidden to purchase ermine coats.

Ludovico Sforza, the white ermine

While for a long time it was assumed that the ermine was merely an allusion to the surname of Cecilia Gallerani, the discovery of a historical document made it more likely that the mistress of the Duke of Milan Ludovico Sforza is actually depicted here.

For around 1900, historians discovered that Ludovico was presented with the Order of the Ermine by the King of Naples in 1488, which earned him the nickname "Ermellino Bianco" (white ermine). The representation of the white ermine in the painting is thus also to be understood as a symbol for the duke.

This explains why the ermine in the portrait is much more muscular and almost twice as big as in reality. It should show the duke, if as a weasel, then as the largest and strongest weasel.

Ludovico never commissioned his court painter Leonardo to paint a portrait of himself. There are only a few other contemporary portraits of the influential duke of Milan

Illustrates the legend according to which an ermine would rather be slain than sully its white fur: "Malo Mori Quam Foedari" ("Better die than be sullied")

Image Analysis

Leonardo manages like no other through facial expressions, gestures, posture and symbolism to build up a depth of meaning that must captivate every viewer. In his paintings, he interweaves the most diverse levels of meaning in an extraordinarily elegant way, interweaving them in equal measure and thus turning them into a mystery. This is also what makes an interpretation of his paintings so difficult.

Image description

A young woman in three-quarter profile, in a dark room, lit from the right. She has turned her torso away from the light, but her head toward the light. She is looking out of the picture space on the right. On her left arm she carries an ermine in a white winter coat, which she presses tightly against her with her right hand.

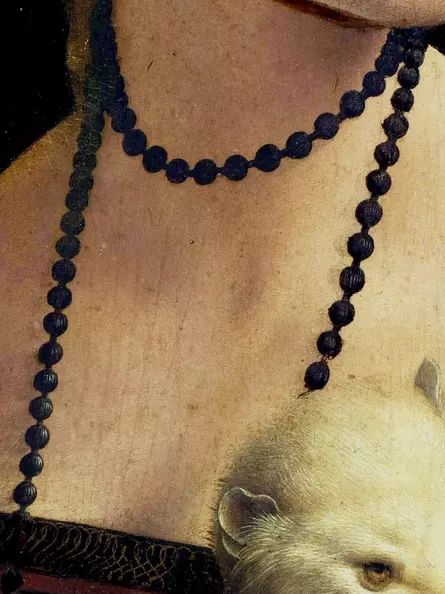

Her hair, lying close to her head, has been parted and braided into a plait at the back. Around the head a narrow, dark-colored band over a transparent hood with a golden edge, which is pulled deep into the face up to the eyebrows, the straps are gathered under the chin. Around her neck a long pearl necklace, laid twice into a short and a long piece. She wears the elaborately tailored dress of a noble lady. In the upper left corner in gold letters:

LA BELE FERONIERE

LEONARD DAWINCI

Representational errors and conspicuousness

Leonardo intentionally uses subtle errors, aesthetic conspicuities, and geometric constructions to draw the viewer's attention and provide clues to interpreting the painting.

The most noticeable flaws are:

- The sharp contours of the facial part are reminiscent of Venetian full masks (bautas)

- The lady's right hand is too big compared to her face and looks less feminine, almost masculine

- Her left hand cannot possibly hold the ermine, but is still curved outwards

- The ermine is depicted much too large, it should actually be only about half that size

The double images in the painting

The story of a love affair

The ermine is the central element of the painting, along with Cecilia Gallerani. No doubt it is an allusion to the couple Ludovico and Cecilia. Ludovico had been presented with the Order of the Ermine two years earlier and was given the nickname White Ermine.

From Cecilia's surname Gallerani, a pun can be derived with the ancient Greek galê or galéē for weasel.

However, these connections would also mean Leonardo did not adopt the ermine into the painting on his own. The circumstances of his noble client forced him to choose this animal.

Leonardo now tells the story of the two lovers in his painting. But he goes beyond that. It will be seen that he abstracts their narrative and uses it to elevate it to the story of any young love. In this way, he manages to create a timeless work that tells a story that is always true, completely independent of the knowledge of the sitter's circumstances. This is what makes the mystique of the painting and fascinates countless viewers to this day.

The maturity of Cecilia

Cecilia wears a necklace of black pearls around her neck. Pearls are created when impure enters a shell. It is held by it and woven around with mother-of-pearl. Then, when the pearl is large enough, the shell opens and presents its beauty. Therefore, since ancient times, pearls were considered a symbol of virtue, but also of fertility.

The dream of Cecilia

Cecilia stands as a young woman in a dark room, alone, almost as if in a dream. As if to calm her fear, a pet in her arms. Her gaze goes into the bright distance. Her gaze seems awake, her expectation of the future clear. But for the moment, she is still surrounded by absolute darkness.

Getting to know each other

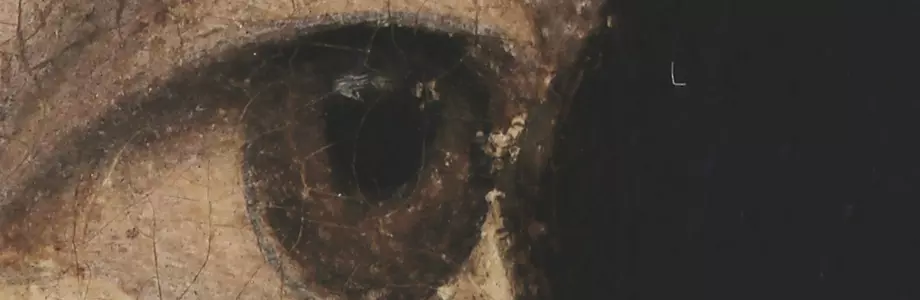

A woman in a dark room, alone, with a pet in her arms. She turns towards the place of the stimulus. It is unclear whether the stimulus was a sound or the light, which caught her attention. But in the context of the painting, a hypothesis suggests itself here. It could be Ludovico who enters the room. He opens a door and appears in the light. In her eyes is reflected a person walking down a basement staircase. A bird rises in the background. The scene seems like a liberation.

Cecilia's pupils reflect what she sees. The outline of a head can be seen descending from the light into a cellar. A bird soars in the background. Getting to know is Cecilia's liberation from darkness

Also in Cecilia's left eye the contour of a head is recognizable

An act of love

Cecilia is still very young when she is paired with the duke (16 years). Thus Leonardo depicts her in this picture as very young, almost childlike. The oversized ermine reinforces the almost childlike impression, because if it is not too big, she is too small.

Cecilia turns away and turns towards. For a playful expression of her insecurity, she holds a pet in front of her belly, her head always curiously fixed forward. Her right hand somehow doesn't seem to fit quite right. It is first too big, then also too tense. It doesn't seem to belong to her. Her left hand doesn't seem to belong to her either.

If the hands and forearms don't belong to her, both arms seem to come out of the darkness behind her, as if the darkness itself is reaching for her. Ludovico's official epithet was Il Moro, the Black. Paying attention only to her hands, a veritable dance of hands emerges on her body. Sometimes the delicate masculine hand to her right, sometimes the rough hard grasping hand to her left, and then it's her own again. And again not, and the game begins anew.

The masculine rawness is exaggerated in the figure of the white ermine, which seems to have just torn open Cecilia's blue sleeve with its claw-sharp right hand and now leans triumphantly over her left elbow. The left paw looks down.

This area of the ermine illustrates the erotic character of the painting. The exaggerated animal musculature of the ermine bears undeniably human features. The ermine's left paw has conspicuously forward falling hair. The animal's obese belly seems equally humanized. And indeed, according to the few contemporary depictions, the Milanese duke was somewhat more corpulent. This supports the assumption that the ermine is a symbol for the duke.

The exposed breast

The erotic character of this scene is complemented by the ermine's head, which blends in color with the skin tones of the lady's décolleté. The pointed shape of the ermine's head is reminiscent of an exposed female breast, which the lady's downward moving right hand seems to have just uncovered #. The mouseover effect here imitates a blurred view of the painting, such as is achieved with watery or tired eyes.

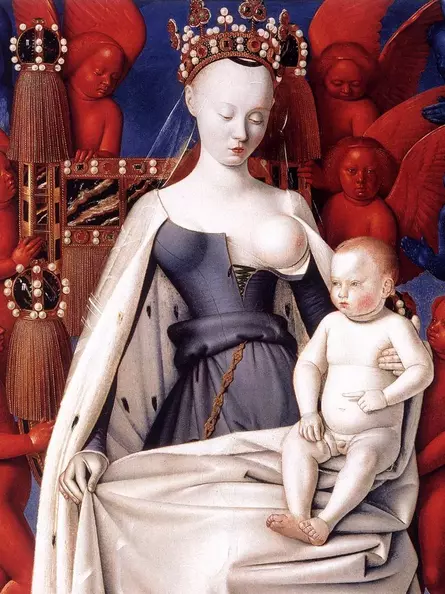

A naked breast was only allowed to be shown in a religious context due to general church censorship, for example with the nursing Mary, the mother of Jesus. Such a type of image is called Madonna lactans (Engl. 'milk-giving Madonna'). But depictions of naked goddesses of classical antiquity were also permitted, such as in Botticelli's "Birth of Venus" (c. 1485), which, remarkably, analogous to the nursing Mary, keeps one breast covered in order to emphasize the demure character of the painting.

The index and middle fingers spread for breast-feeding are reminiscent of the hand position of the lady with the ermine. Remarkable is the deformation of the breast directed to the child

The medieval image type of the breastfeeding Madonna was very common especially in northern alpine painting

In this depiction it becomes particularly clear that the reference to the nourishing Madonna often served only as a pretext for depicting exposed female breasts

The suggestion of a bared breast in a normal portrait was a fashion that did not emerge until the end of Leonardo's life. He died in 1519 at the age of 67. His young admirer Raphael (*1483), in particular, later adapted it here as well. Where Leonardo still hinted, Raphael executed. It was not until his generation of painters that he took more liberties in creating portraits.

The lady's hand position is reminiscent of the implied exposure of the breast of the lady with the ermine. Raphael was a great admirer of Leonardo's painting

Raphael used this gesture several times in his portraits. It is interesting here how the slightly darker fingernail of the index finger is used to indicate the position of the nipple

Here the undressing index finger pushes the already opened corset forward

What all the portraits shown here have in common is that the right hand touches the left breast of the sitter, and yet the pictorial effect achieved is always different. From left to right, the nude is covered more and more and in a playful, almost erotic way.

Thus, although Raphael's portraits of women are stylistically reminiscent of the lactating Madonnas shown above, he also depicted the female breast in an erotic context. The interplay of breastfeeding and erotically revealing gestures is very reminiscent of the portrait of the Lady with an Ermine. Raphael constantly quoted from Leonardo's paintings.

The pregnant belly

After this act, the pregnancy is now referred to compositionally. The lady's unfinished left arm, blurred in the shadows, cannot possibly hold the ermine. The hind legs of the writhing animal would have to be between her hip and the right arm and thus above her left hand.

If only the area of the left hand is considered, it quickly becomes clear that the lady is holding her left hand on a pregnant belly. But the illusion dissolves as soon as the view leaves the left hand.

The left hand resting on the belly is a typical hand position of pregnant women

The birth

In an elegant upward movement from the left hand holding the pregnant belly over the strangely round belly/back of the ermine to its left paw, the gaze reaches the conspicuous drapery on her left sleeve.

The sharp-clawed and strong ermine seems to have just torn Cecilia's sleeve open from top to bottom with its right hand and parted it in such a way that the red underneath is now visible, the glimpse bordered by delicate orange hem.

To the left and right of the apex of the hemmed triangle there is a curious blue drapery, reminiscent in its symmetry of a pair of human eyes. Accordingly, the red triangle below - a wide-open mouth - would be the missing complement of an oversized face screaming to the upper right.

Certainly only vaguely and more a caricature, Leonardo here hints at the horrors of childbirth. That at the end of the birth canal is an open, loud screaming mouth, must be seen before the ancient superstition that stoats give birth to your children from the mouth. The humorous cartoon thus refers to this ancient legend.

The child in the arms

Leonardo ends the narrative of the love affair with the depiction of the proud mother Cecilia. If the ermine is mentally faded out and attention is paid only to the posture of the hands, this corresponds to that of a mother carrying her child in front of her. The head of the child at her left breast.

It fits then also that the head of the ermine merges in color into the décolleté of the lady. The head of the ermine tapering to the right can be seen as a breast bared for nursing the child #, as shown in the example of the Madonnas above.

Conclusion on the history of the love affair

It could be shown that Leonardo directs the viewer's gaze via flaws and aesthetic conspicuities, and combines them in their entirety to form a consistent whole. The painting tells of Cecilia's young love life, beginning with her maturity, her dream of love, meeting Ludovico, their lovemaking, Cecilia's pregnancy, the birth that follows, and finally her happiness as a young mother.

Leonardo has painted a work about love, even more: about any love. Viewers do not need to know who is shown to understand the atmosphere of the painting. Every person can intuitively grasp what is shown, without concretely knowing what is fascinating here.

The feat that Leonardo achieved here was to create a work that was so understandable in its time and for the clients that they could identify with it. But also so that following generations, who no longer know their story, could understand the pictorial narrative: the love of a young woman and a man.

And so it happened that Leonardo called the lady's face the dungeon of love. The innermost dungeon is her unrequited love, her body itself, the outermost her obligations as a young mother. The dungeons in between accordingly.

Composition

The painting contains some geometric features. Geometry not only adds an artistic expression. It is also part of the self-image of Leonardo da Vinci, who, as an astronomer and earth surveyor, was looking for a divine harmony. He assumed this to be in whole-number ratios in nature, but also in mathematical constants, such as the golden ratio. Leonardo's countless geometric drawings on his sketch sheets are famous, as are his illustrations of three-dimensional geometric objects for the mathematician Luca Pacioli's book on the golden section.

The painting contains representational errors and conspicuous features that have a geometric character

- the strictly formed hair emphasizes the middle parting strikingly in one point

- her plain black headband is too straight for a band around her round head

- the golden headband appears parallel to the black headband and curved only towards the edge

- the stoat's eyes and right ear appear arranged in an equilateral triangle

I The look of the ermine

Leonardo paints an ermine looking happily at onlookers, which is made clear by the construction lines.

- the golden section of the picture width runs through the left eye of the ermine (orange line)

- the golden section of the image height runs through the right eye of the ermine (orange line)

- the central perpendicular of the image width passes through the right ear of the ermine (red line)

- the stoat's right eye is exactly in the middle of the central vertical line (red) and the golden section of the image width (orange line)

- the three points can be connected to an isosceles triangle (green triangle). The interior angles are 120° and twice 30°.

With this knowledge, the three points now transform into a second version superimposed on the original face of the ermine, which smilingly looks directly at the viewer (I + mouseover). This exemplifies the knowing and humorous spirit typical of Leonardo's painting, with which he conceived his works.

The ermine is the guardian animal of pregnancy. A smiling ermine indicates a happy birth.

II The look of Cecilia

With the knowledge of the stoat's face, the face of Cecilia is now examined.

- Bounded by the golden section of the picture's height (orange line) and the central perpendicular (red line), a square spans the right edge of the picture (red cross line). The upper line of the square runs through both eyes of Cecilia

- from Cecilia's middle vertex a 45° angle meets both eyes (white lines)

- from the just drawn square a rectangle can be drawn upwards to the black headband. This has the aspect ratio of 4:3 and its lower edge is exactly at 3/4 of the image height

- from the height of its black headband a line can be drawn downwards to the paw of the ermine, which is also divided by the horizontal golden section in the golden ratio (yellow line)

- The stoat's right paw rests on a 45° angle (green triangle) which is bounded on the left by the center of the image and on the right by the golden section. It is the same triangle that appeared above her face (green triangles).

The right paw of the ermine, here as the heraldic animal of Duke Ludovico, resting on the lower triangle, stands in the masculine-erotic context (see "An Act of Love"). The upper triangle is in the context of Cecilia's gaze. The fact that both triangles are approximately equal in size, that is, harmonious, allows the interpretation that the amorous relationship of the two is happy at the time of the painting's creation.

III The House of Santa Claus

Known today mainly as a children's game, the House of Santa Claus is one of the simplest examples of connecting points as efficiently as possible by routes, here there are five points. The problem can quickly become very complex as the number of points increases and the positions change. The famous mathematician Leonhard Euler first studied the problem in more detail in the 18th century (Königsberg bridge problem).

Until today, the so-called graph theory is a subfield of discrete mathematics or theoretical computer science. If, for example, Google Maps suggests the fastest way from point A to B, the program makes use, among other things, of the findings of graph theory.

Leonardo da Vinci must have also dealt with the question about 200 years before Euler, which manifests itself in the pictorial geometry of the lady with the ermine.

- From Cecilia's right eye, the vertical center of the picture, a 22.5° angle leads to the point where the vertical golden section meets the golden headband (green lines). The 22.5° angle is the center angle of a regular hexagon

- likewise, from the base of her left eye, a 22.5° angle leads to the intersection of the golden headband and the central vertical line

- From the intersection of the two lines an angle of exactly 72° (see golden section) can be drawn to the already known point of the central vertex, the center angle of a regular 5-corner (dark blue line)

- The angles from the golden headband to the point of the central vertex are also not chosen at random, they are counterclockwise starting from the lower left and are successively 45°, 75° and 60°. The result is the triangle that Leonardo always staged in all his portraits starting from the middle parting (green area), e.g. in the Belle Ferroniere, John the Baptist or the Mona Lisa

The triangle of left and right eye and central vertex has the interior angles 45°, 60° and 75°. The white line is the central perpendicular of the painting

Leonardo constructs the same triangle in this painting. The white line is the golden section of the width of the picture

- If one connects now all points just determined, the pattern known today as the house of St. Nicholas results (green lines in the forehead area)

- By geometrical displacement the upper green-surfaced triangle of the forehead can be shifted downward in a straight path in such a way that it rests on the already existing isosceles triangle at the head of the ermine (lower green-surfaced triangle). The triangle shifted in this way is exactly the same size as the one on her forehead. The upper tip of the lower triangle is exactly at the tip of the stoat's left ear. Thus, both ears and both eyes of the ermine are geometrically related

Conclusion to the geometrical analysis

It has also been shown in this painting that Leonardo weaves distinctive points, lines, and shapes in the painting with a geometric network, thereby enhancing the depth of content.

Most striking, and in contrast to the other Leonardo portraits, is the strong emphasis of the painting's geometry on the narrow area between the central vertical and the vertical golden section (red and orange verticals). All of the image geometry takes place there. The vertical character and the tripartition of the sense units create the impression of a geometric projection from top to bottom. In its course, a triangle is shifted, rotated and tilted in three phases.

In comparison with the geometry of other Leonardo paintings, the Lady with the Ermine appears quite simply constructed overall. Remarkable is the fact that Leonardo here only sets a square in scene II, which spans from the golden section of the picture height to the eyes, bordered on the left by the central perpendicular, on the right by the picture edge (red line). Defining for the Belle Ferroniere is a division into four squares, in the Mona Lisa there are six squares.

Classification in the overall work

In view of the increasing complexity of the geometric dependencies in Leonardo's later works, the assumption thus suggests itself that the Lady with the Ermine would be the prelude to a three-part series of portraits that would conclude with the Mona Lisa. Since only a few of the paintings still attributed to Leonardo today have a consistent geometric scheme in this respect, this is the key to further narrowing down the attributions to Leonardo.

Conversely, however, this should not mean that a complex pictorial geometry inevitably proves an authorship by Leonardo, as the example of the Portrait of Ginevra de' Benci makes clear. The painting is said to have been created about 15 years before the Lady with the Ermine, but it is much more complex in terms of pictorial construction. The numerous and clearly recognizable double images also contribute to this impression. However, especially by analyzing the geometry of the picture, reasonable doubts arise that it is a work by Leonardo da Vinci.

Against this background, it is a mistake to disregard the geometry in Leonardo's paintings when discussing the authenticity of his paintings. Leonardo's universal understanding of geometry was always an integral part of his works, as will be evident in all of his paintings discussed here.

The Lady with the Ermine is Leonardo's least complex work in this regard, and must therefore be considered the beginning of a cycle of paintings characterized by the fact that the paintings were interwoven through geometric symbolism.

The geometric dependencies and especially their constructions are much more varied in this extraordinary, nearly square portrait than in the Lady with Ermine painted almost 15 years later

The double images, however, are more clearly worked out in comparison to the lady with the ermine

Leonardo's love for nature

Leonardo was a vegetarian and saw nature first in everything. Depriving an animal of its freedom and caging it for his own pleasure must have seemed deeply alienating to him.

The domestic animal husbandry

Ermines feed mainly on small rodents. As a result, people at the time of Leonardo da Vinci often kept them as mouse hunters. To fight plagues of mice with cats appeared in Europe only later.

About the quite practical problems of a domestic animal attitude it gives references, which should let think whether the creatures of nature should not be better in freedom, instead of robbing these e.g. because of their soft fur of their freedom. Particularly since it is nevertheless very laborious to hold the creatures striving by nature for freedom. The weasel escaping from the lady's firm grip, its tense right paw already ready to jump and its hind legs also eluding the lady's grip, indicate the animal's urge for freedom.

Leonardo shows in the left sleeve (orange hem) how sharp-clawed a pet can be, which seems to have just torn open the blue sleeve of the dress from top to bottom with its right paw, revealing the red fabric underneath.

Also the biting instinct of the animal, is indicated by dark spots around its mouth. They could be from coagulated blood from a previous bite by the predator.

In addition, the lady's nose is located right above the stoat's nose. An indication of the strong body odor of the stoats.

Vegetarianism and meat consumption

And finally, the lady's black necklace speaks to Leonardo's understanding of the relationship of man to animal. Where the links are not sculptured into spheres, where no light source is reflected, i.e., in the immediate vicinity of the neck, they are reminiscent of plate-shaped lentils, much like black lentils, which, due to their high protein content, serve as a meat substitute today, especially for vegans. Leonardo was a vegetarian.

Whereas the balls on the right look like dried black fruits, much like peppercorns, which were often served with meat. Thus the chain, completely in Leonardo's understanding, is an indication to ask nature first for alternatives than to eat the living beings inherent in it without need.

The naturscientific aspect

The court of Milan was politically very close to France. The Duke of Milan Ludovico maintained close diplomatic relations. Leonardo also established contact with them, as they admired his art. When Milan was later conquered by the French, Leonardo entered the service of the French governor of Milan, and later even the direct service of the French king.

Therefore, Leonardo was familiar with the French translation of ermine, Ermine. Since French people do not speak the H, in French understanding Ermine sounds like the feminine form of the name Hermes, Hermione.

Hermes was a son of Zeus and the nymph Maia in Greek mythology. Thus a god himself, he was entrusted by his father to deliver his messages. The Romans later adopted the god system of the Greeks. However, they changed the names of the gods.

Thus Hermes is now called Mercury by the Romans. He also appeared as Mercurius in Ovid's Metamorphoses.

History of the painting

Today it is hardly disputed that the painting was made by Leonardo da Vinci. The latter was in the service of the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, from about 1483 to 1499. Presumably, the Duke commissioned a portrait of his mistress, Cecilia Gallerani. However, no commission documents, contracts or the like are known.

Since the work variously alludes to the teenage Cecilia's pregnancy, it must have been painted in 1490, since her only child with the duke was born in May 1491.

The historical existence of a portrait of Cecilia painted by Leonardo is sufficiently proven. Among other things, by an exchange of letters of 1498, in which Isabella d'Este asks Cecilia to lend her a picture that Leonardo had painted of her "according to nature". She wanted to compare it to a work by the Venetian painter Bellini. Cecilia complied with the request, but pointed out in her reply letter that the painting no longer resembled her, as it showed her at an "unfinished age."

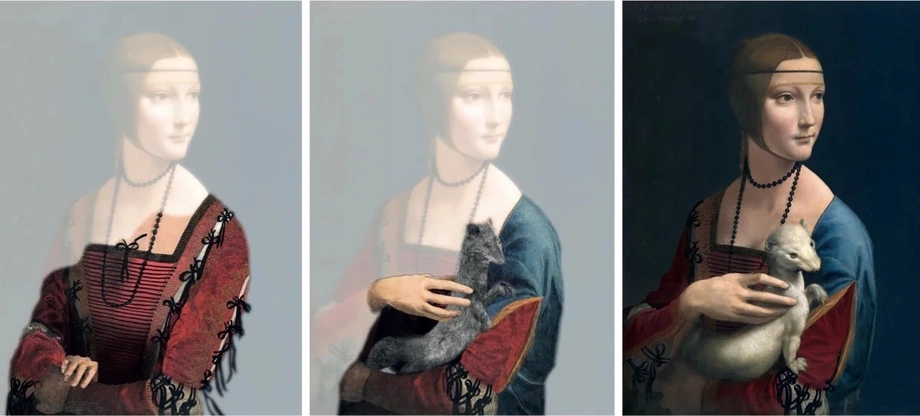

The gradual overpaintings by Leonardo

In the 2000s, the physicist Pascal Cotte was able to reconstruct the phases of the painting's creation by means of a special radiological procedure in a widely acclaimed work.

Originally the picture was created without an ermine, in a second step a gray marten-like animal was placed in the lady's arms, and finally the third version with the oversized ermine, which can be seen today, was created from this.

It is therefore conceivable that the duke was originally only interested in having Cecilia portrayed. When she became pregnant while working on the painting, Leonardo added a weasel-like creature. The weasel has been the guardian animal of pregnant women since ancient times. Probably at the Duke's request, the weasel was then reworked into an oversized and muscular ermine in winter fur. The duke's nickname was "White Ermine".

In the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan

The painting remained in the possession of Cecilia Gallerani until she died in 1536. After her death, the painting initially remained in Milan. As late as the eighteenth century, Carlo Amoretti, the librarian of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, wrote that it was there as part of the collection of the Marchese of Bonasana.

In the possession of the Polish princely family Czartoryski

Around 1800, the Polish prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski bought the painting during a trip to Italy and gave it to his mother Izabela Czartoryska. She built up an art collection and, by making comparisons, mistakenly came to the conclusion that the Lady with an Ermine and the Belle Ferroniere depicted the same people. As a result, she had an inscription placed in the upper left corner of the painting.

LA BELE FERONIERE

LEONARD DAWINCI

Leonard Dawinci is the Polish spelling of Leonardo da Vinci. She probably had other adjustments made: Chain, headband and decorations of the dress were painted over with stronger colors. Also contours of the nose, hair strands and pupils. In addition, she received some rouge on the cheeks. She may also have had the original light bluish gradient in the background painted over into a monochrome black.

Changing whereabouts

The portrait was then located in the "Gothic Cottage" in the Czartoryski residence in Puławy (Poland). Because of a Russian-Polish war, the princely family fled to Paris in 1831. The painting was officially considered lost, but it was in the noble Lambert Hotel in Paris, where the family took up quarters. Around 1871 the Czartoryski family returned to Krakow from exile in Paris, and with them the Lady with the Ermine. In 1876 the painting was exhibited publicly for the first time in the Czartoryski Museum in Krakow.

After the defeat of Poland in World War II, the painting was confiscated in 1939 and moved to the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin (now the Bode-Museum). The painting was then to be exhibited with many other paintings confiscated by the Germans in the planned Führer Museum in Linz. However, the German Governor General of Poland, Hans Frank, came into possession of the painting in 1940 and then had the painting transferred to his residence, the Wawel Castle in the center of Krakow.

When Hans Frank fled to his country home in Bavaria towards the end of the war, he took it with him to where the painting was found by the Americans in 1945.

In the possession of the Polish state

The Americans brought it back to Krakow. Today it is in the possession of the Polish state and is exhibited in the Czartoryski Museum in Krakow.

Significance for the history of art

Leonardo's work also demonstrates here in a superior way how it is possible to create an immense depth of expression with few creative means.

Leonardo's first portrait of a woman is of great importance for art history, because with this depiction of the Lady with the Ermine, the traditional stiff portraiture that had prevailed until then was replaced by a more dynamic rotary movement.

Leonardo's other two portraits of women, La Belle Ferroniere and Mona Lisa, also feature the typical rotation that always creates the impression that the sitter is reacting to the viewer or, as in the case of the Lady with the Ermine, to a third party.

Nature, who excites your anger, who excites your envy?

It is Vinci who painted one of your stars!

Cecilia, who is so beautiful today.

Beside whose beautiful eyes the sun seems like a dark shadow.All honour to you, even if in his painting

She seems to hear and not to speak.

Just think, the more alive and beautiful she is,

the greater will be her fame in times to come.

So be grateful to Ludovico, or rather

To the talent and hand of Leonardo

Which allows you to be part of posterity.

Anyone who sees her - even if it is too late

To see them alive - will say: this is enough for us

To understand what is nature and what is art.

Downloads

Sources

Website of the exhibiting museum: Czartoryski Muzeum, Krakau

Frank Zöllner, Leonardo, Taschen (2019)

Frank Zöllner/ Johannes Nathan, Leonardo da Vinci - Sämtliche Zeichnungen, Taschen (2019)

Martin Kemp, Leonardo, C.H. Beck (2008)

Charles Niccholl, Leonardo da Vinci: Die Biographie, Fischer (2019)

Johannes Itten, Bildanalysen, Ravensburger (1988)

Highly recommended

Marianne Schneider, Das große Leonardo Buch – Sein Leben und Werk in Zeugnissen, Selbstzeugnissen und Dokumenten, Schirmer/ Mosel (2019)

Leonardo da Vinci, Schriften zur Malerei und sämtliche Gemälde, Schirmer/ Mosel (2011)

![[Translate to english:] [Translate to english:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/8/b/csm_leonardo-alle-gemaelde_2dc4b01ef6.webp.pagespeed.ce.ohfmgl8OfF.webp)