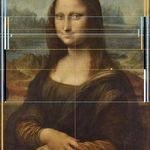

Mona Lisa

The Mona Lisa is a painting by Leonardo da Vinci, which he began around 1503 and worked on until his death in 1519. It depicts a mysteriously smiling woman known as Mona Lisa. The identity of the Mona Lisa is unresolved, but the majority of researchers believe it to be Lisa del Giocondo. The Mona Lisa is considered the most famous and renowned artwork in the world and is often regarded as the epitome of Renaissance art. The portrait is called La Gioconda ('the joyful one') in Italy and La Joconde (from the Italian 'Gioconda') in France. The painting is currently housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Facts

Painting | |

| Painter | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year of origin | 1503-1519 |

| Epoch | Renaissance |

| Genre | Portrait painting |

| Technique | Oil on poplar wood (sfumato technique) |

| Dimensions | 53,4 × 79,4 cm |

| Exhibition venue | Louvre Museum, Paris (Room 711/ Salle des Ètats) |

| Owner | French state |

| Wert | over 1 billion dollars (estimated), is considered the most valuable painting in the world, but is not for sale |

Lisa del Giocondo | |

| Birth name | Lisa di Noldo Gherardini |

| Born | 15.6.1479 |

| Zodiac sign | Gemini |

| Nationality | Italian (Republic of Florence) |

| Social status | Noble |

| Place of residence | Florence |

| Parents | Antonmaria Gherardini (Landowner) and Lucrezia del Caccia |

| Siblings | 3 brothers, 3 sisters |

| Husband | Francesco del Giocondo (wealthy cloth merchant) |

| Descendants | 5 Children |

| Deceased | 15.7.1542, at the age of 63 |

| Place of death | Convent of St. Ursula, Florence |

Why is the Mona Lisa so famous?

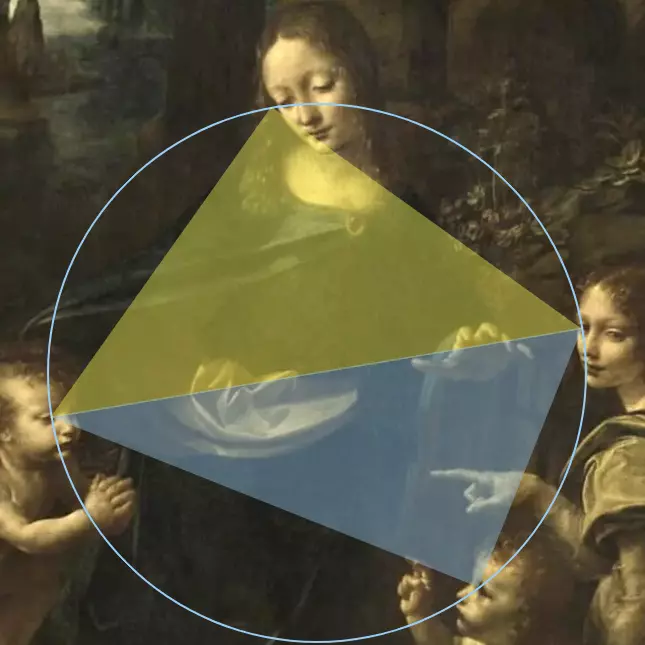

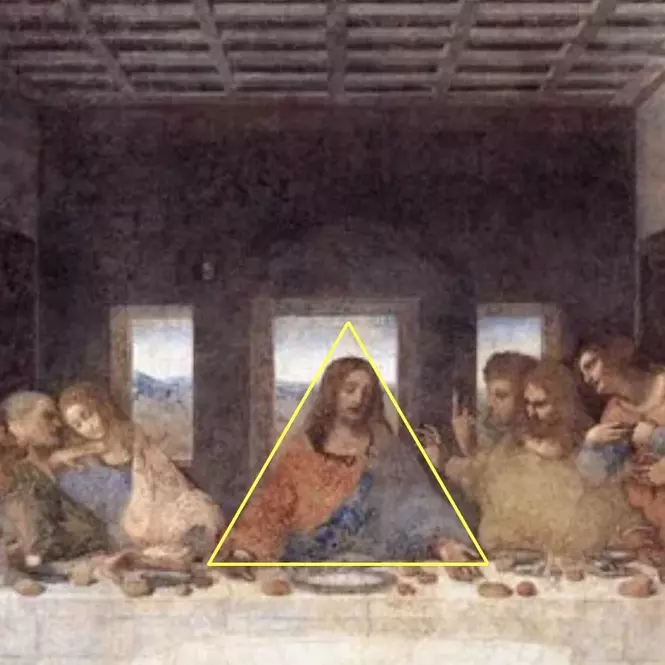

The Mona Lisa concludes a three-part portrait series by Leonardo and showcases his painting technique at its zenith. Many people are captivated by the beauty and grace of the Mona Lisa, considering it a masterpiece of art. The vividly lifelike painting is famous for the subtle emotions it conveys, featuring numerous references to Leonardo's thoughts, geometric symbolism, double imagery, and exceptional craftsmanship. Mona Lisa's famous smile seems to hide something mysterious, and it almost appears as if she is reacting to the observers. Before Leonardo's Mona Lisa, no portrait had achieved such interaction. The portrait proves that painters can create in a moment what poets may need thousands of words for. Thus, the timeless portrait is a visual poetry, depicting Mona Lisa as an educated mother on planet Earth.

The Mona Lisa is also famous for being one of the most studied and analyzed paintings in the world. There are many theories about who the woman in the painting is and why she is smiling, leading to the creation of numerous myths and legends over the years. All of this has contributed to making the Mona Lisa one of the most iconic artworks in the world.

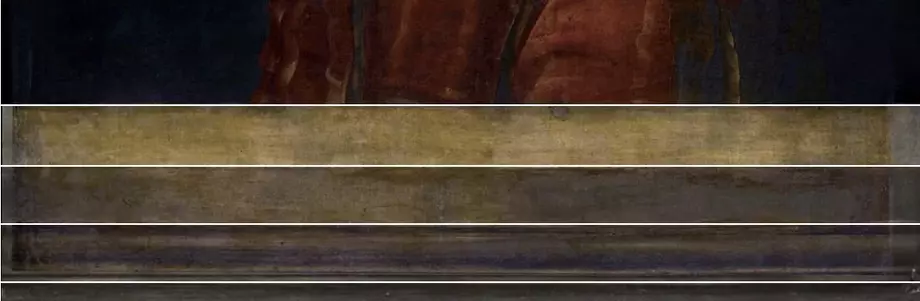

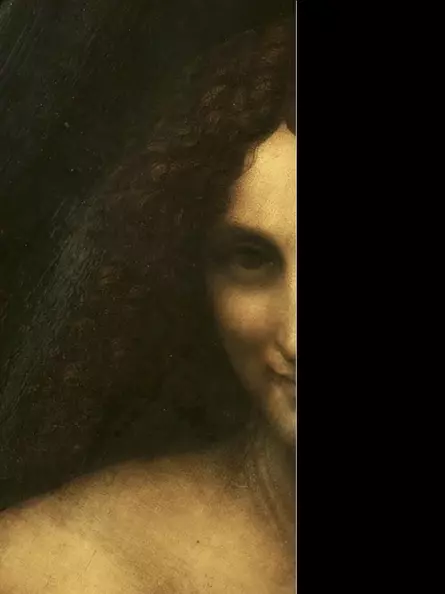

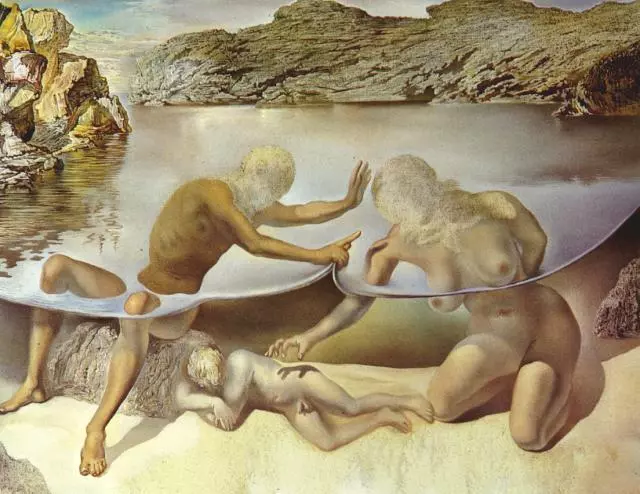

The Lady with the Ermine depicts a young woman who appears childlike and shy in a dark room

La Belle Ferronière portrays a self-assured young woman behind a wall

The Mona Lisa depicts a mature, motherly-looking woman in front of a wall. The surrounding darkness has transformed into a landscape

Who was the Mona Lisa?

The portrait originally depicted a lady from Florence, likely Mona Lisa del Giocondo, born Lisa Gherardini. Mona, or Monna, is not a given name but the Old Italian abbreviation for the address Madonna ('My Lady'). With rare permission from the Louvre, physicist Pascal Cotte examined the precious painting between 2004 and 2015. Using an innovative method, he demonstrated that today's Mona Lisa is a repainting of a portrait underneath. While the underlying portrait bears some resemblance to the current one, it significantly differs in the face. This showed that Leonardo altered the original portrait of Lisa del Giocondo over many years until an idealized female figure emerged. The present version likely does not depict a real person with high probability.

He reconstructed an original version of the Mona Lisa based on the chronological order of the paint layers. It is highly probable that this is the original portrait of Lisa del Giocondo before Leonardo transformed it into an idealized female figure

@Pascal Cotte / Lumiere Technology

This painting is often associated with Leonardo's Mona Lisa due to its characteristic columns.It shows many parallels to the original version of the Mona Lisa (hairstyle, posture, sleeves, shoulder veil). Both painters, Raphael and Leonardo, were in Florence at the time the Mona Lisa was created. They were well acquainted with each other. Raphael was a great admirer of Leonardo's painting and frequently imitated his paintings

In this painting, too, radiological examinations by Pascal Cotte led to the realization that the white ermine was originally intended to be depicted as a life-size weasel

@Pascal Cotte / Lumiere Technology

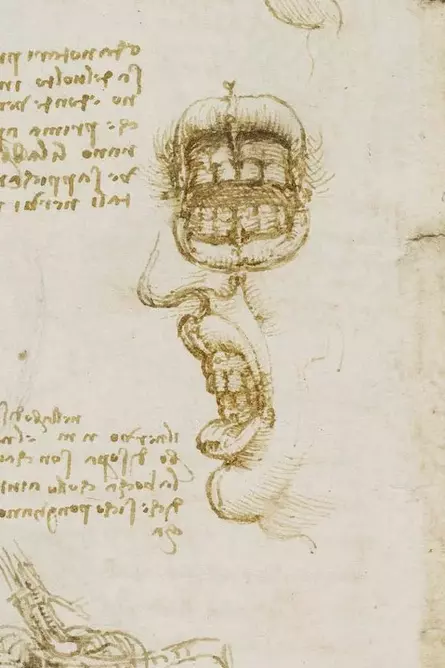

Was the Mona Lisa ill when she was painted?

Mona Lisa shows three symptoms of illness. Firstly, she has a yellow spot between her nasal bone and her left eye. Secondly, there is a bump on her right hand. The Mona Lisa is also missing her eyebrows. As Leonardo's anatomical studies gave him extensive knowledge of the human body and its diseases, he is also considered the best painter of all time and the Mona Lisa of today probably does not depict a real person, Leonardo must have imagined these symptoms. However, Leonardo did not originally paint her yellowish shimmering skin in this way. Rather, the painting has become slightly discolored over the centuries.

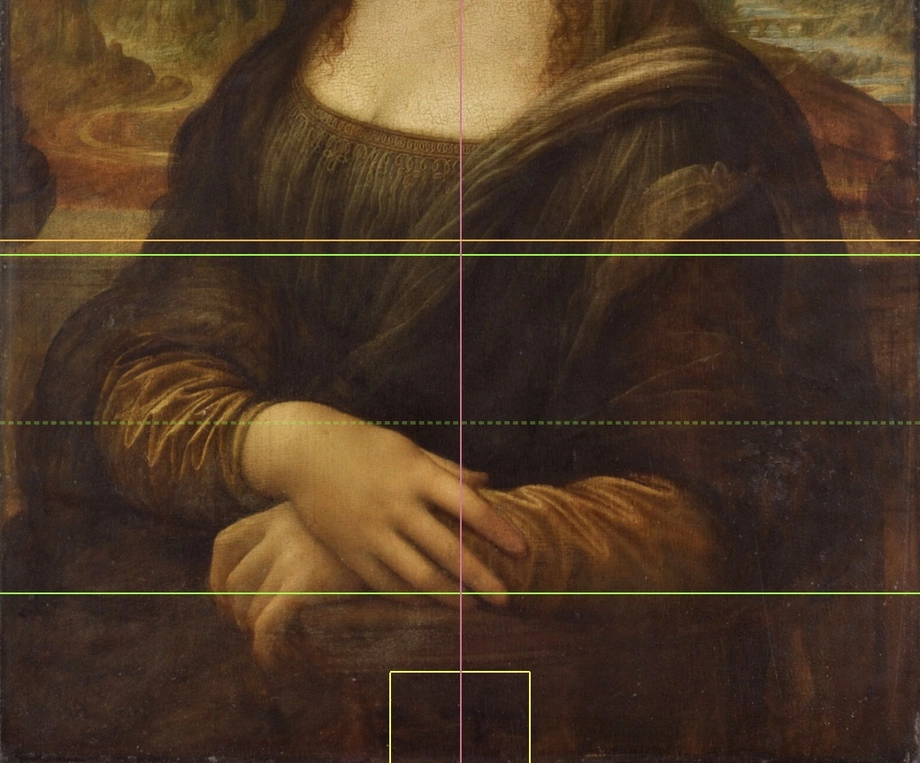

The different perspectives of the Mona Lisa

A special feature of the painting is the use of multiple perspectives. Although the Mona Lisa is depicted frontally, the background of the painting shows landscape elements from three different angles, recognizable by the three different horizon lines. In reality, however, it would be impossible to see such a landscape from different viewing heights at the same time. The impossibility of this idea makes it clear that the background landscape is more the product of Leonardo's imagination and that the depiction of a real landscape is impossible. However, it is possible that certain elements, such as the stone bridge on the right-hand edge of the picture, were real models. Overall, the background seems more like a painted backdrop, comparable to the backgrounds in the theater. Similarly, in the early days of portrait photography, painted backdrops were used to conceal the plain walls of photo studios. However, if Leonardo has deliberately alienated the background of the painting, he is literally inviting us to examine it more closely.

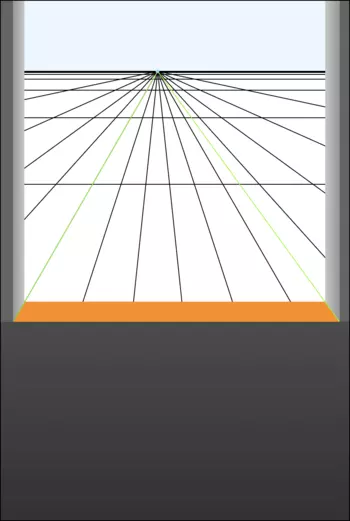

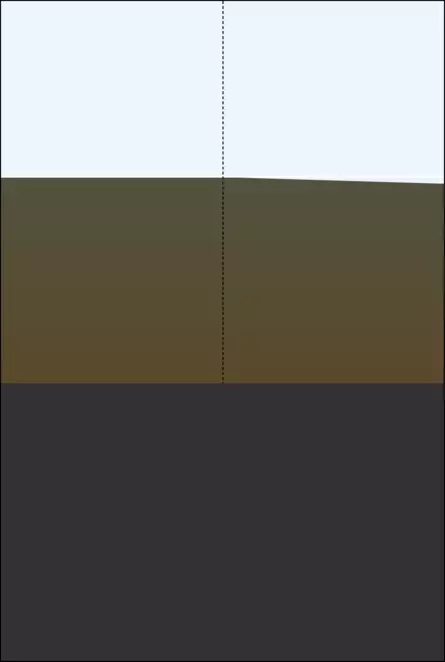

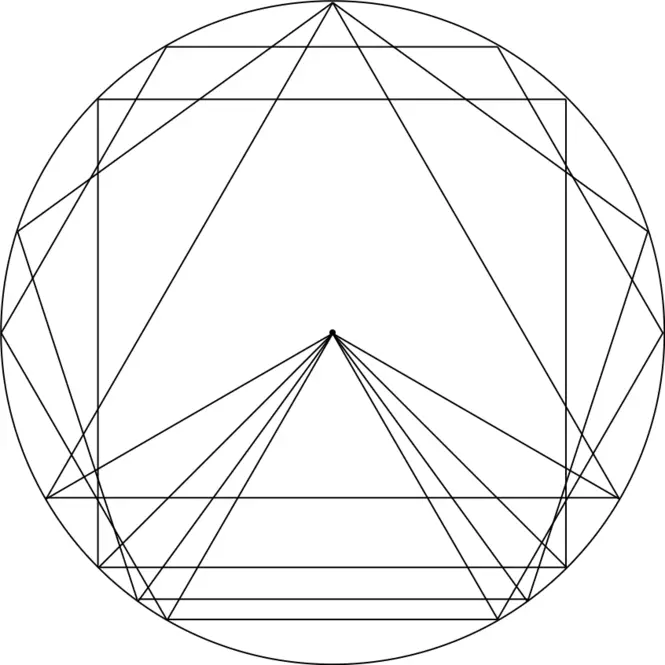

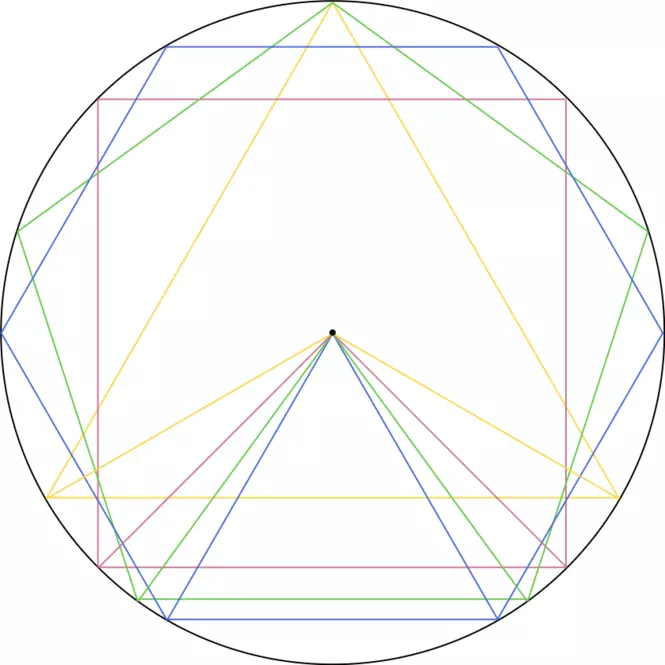

The edges of the column bases on the wall serve as vanishing lines. They meet at the vanishing point, which is exactly at the center of the Mona Lisa (green lines). The sketch clearly shows that the architecture of the loggia is viewed from above, as if the observer were looking at the wall from a standing position. However, this contradicts the depiction of the Mona Lisa, which is shown frontally

The second horizon line, recognizable by the foggy structure in the background, is lower than that of the central perspective.This means that the horizon line is now viewed from a higher vantage point

The circular third horizon line lies at the lowest point. Such a curved earth horizon can only be explained by a view from a very high altitude, e.g. from a stratospheric balloon or a space station.

Viewed one after the other, the three perspectives are reminiscent of a cinematic upward movement that begins in a room and ends high up in the sky

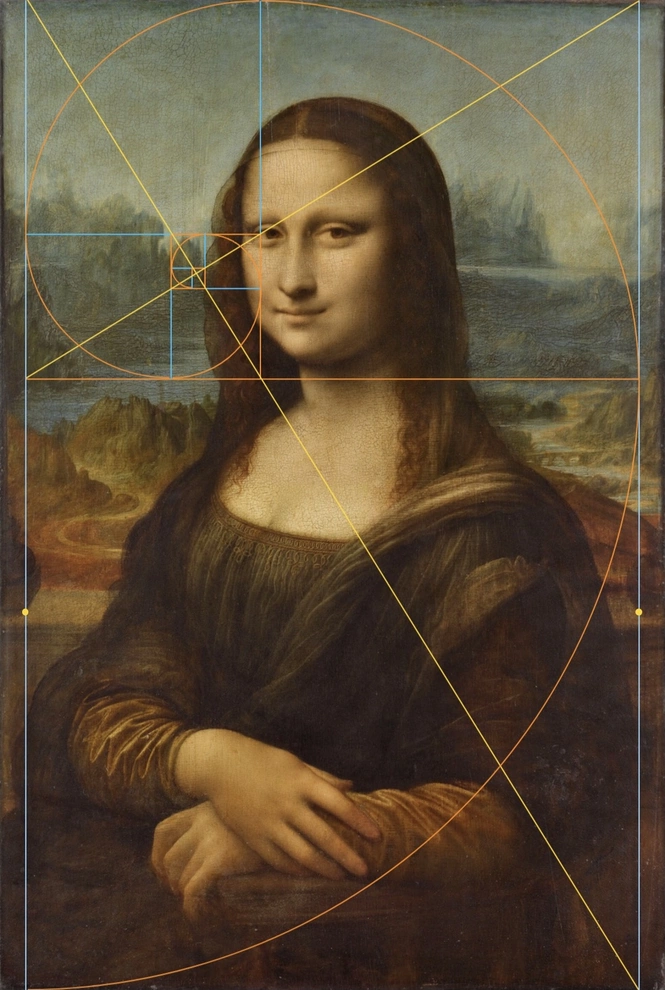

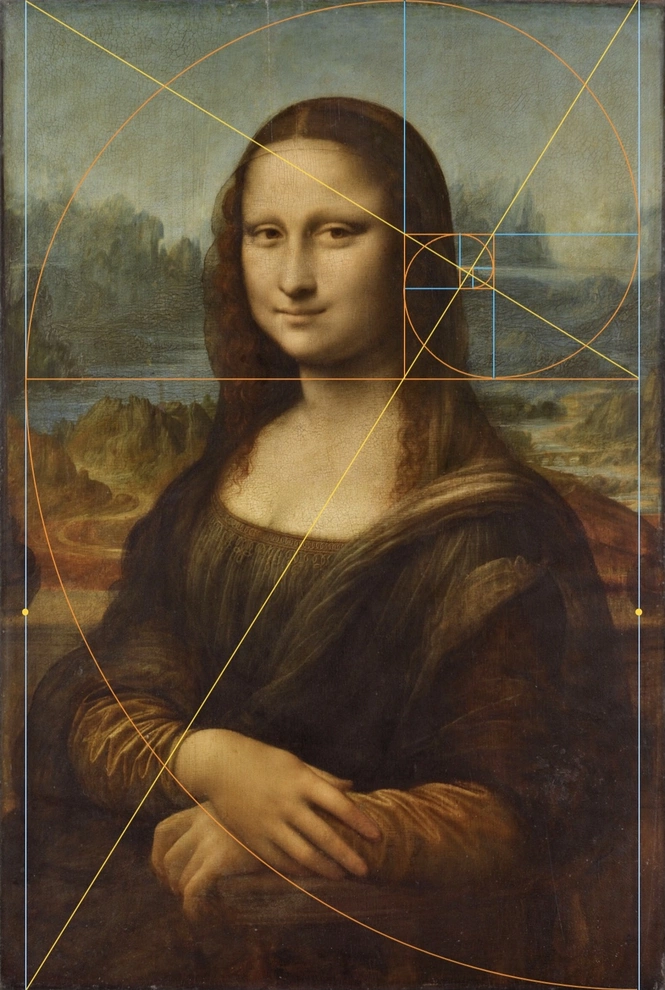

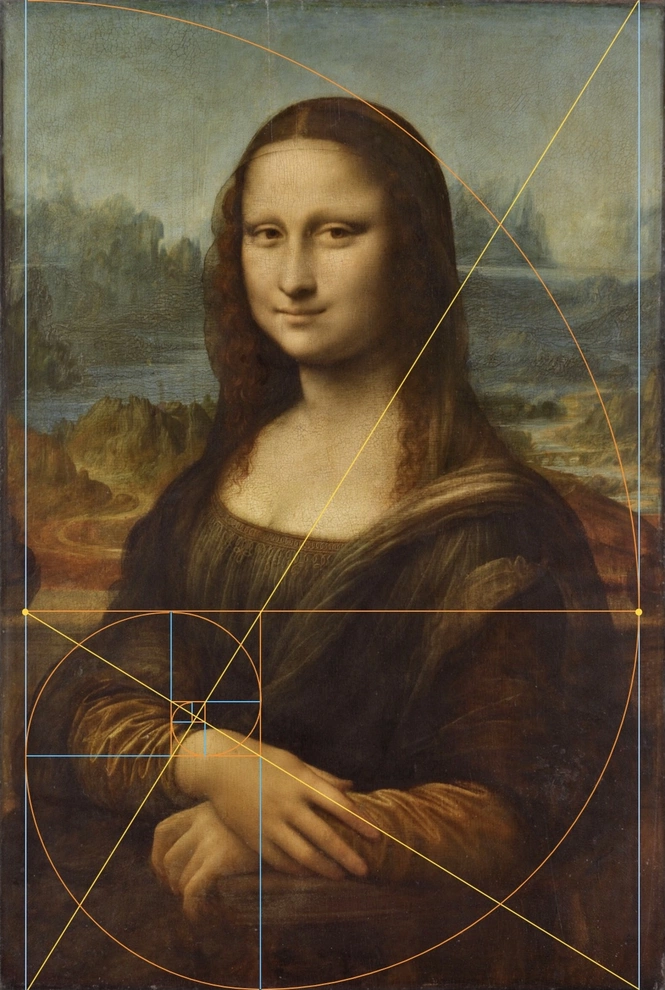

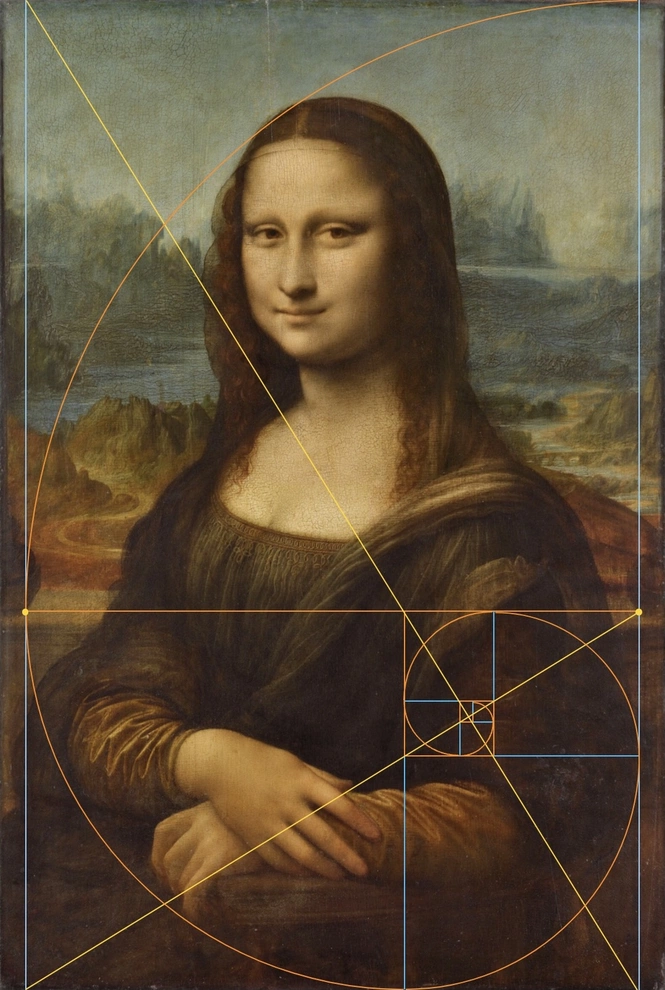

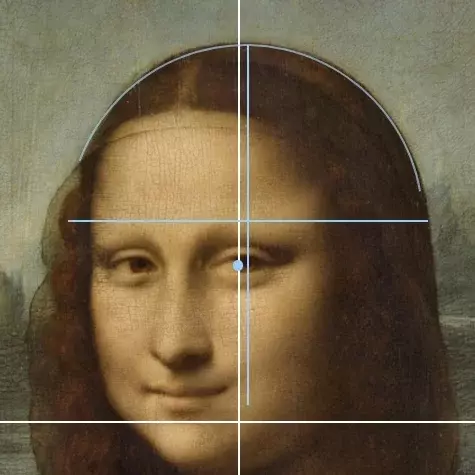

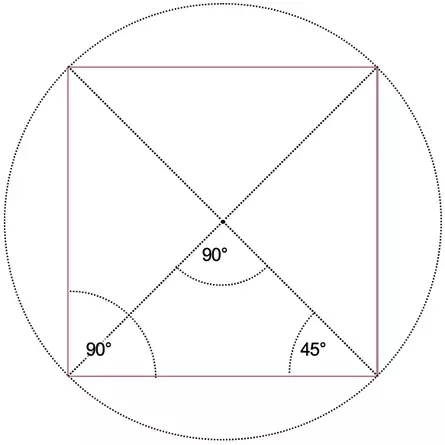

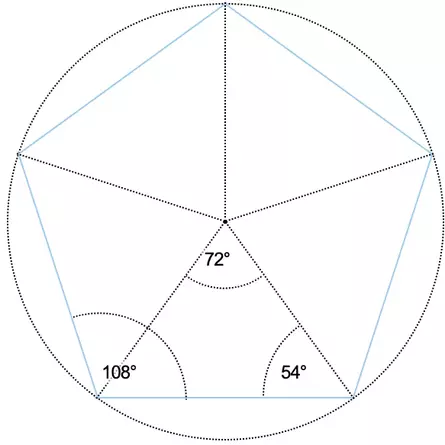

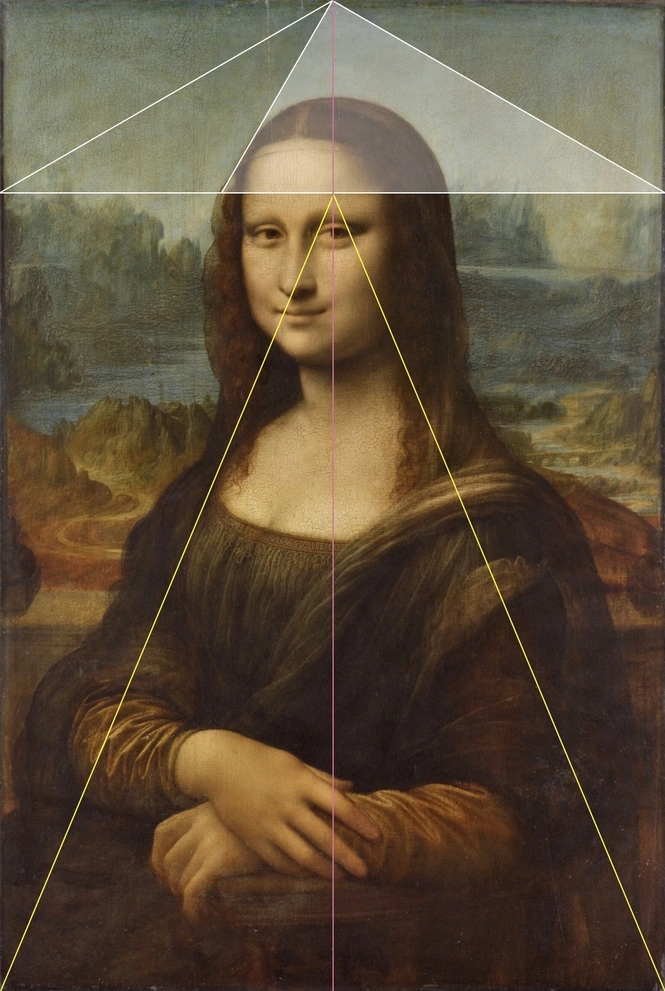

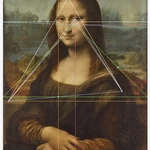

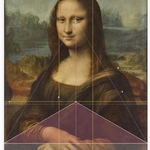

Did Leonardo use the golden ratio?

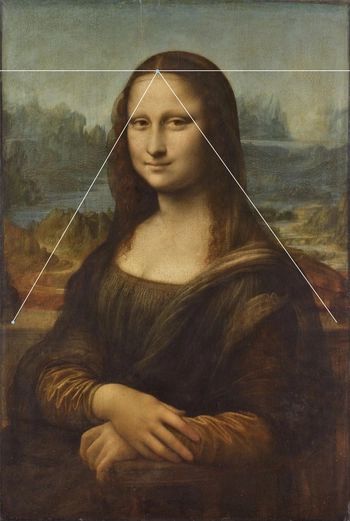

The golden ratio is a certain division ratio of a distance in which the smaller part is in the same proportion to the larger part as the larger part is to the whole. For a distance of length 1, this is the case at ~0.618. Knowledge of geometry is required to divide a distance using the golden ratio. For this reason, the golden ratio and the resulting shapes, such as the regular pentagon (pentagram and pentagon), were long regarded as secret symbols. Leonardo da Vinci's paintings are very harmonious in their composition. In order to achieve this harmony, he always used the division ratios, angles and shapes known from classical geometry. Among other things, the golden ratio, the best known of the classical division ratios, can be seen in the Mona Lisa.

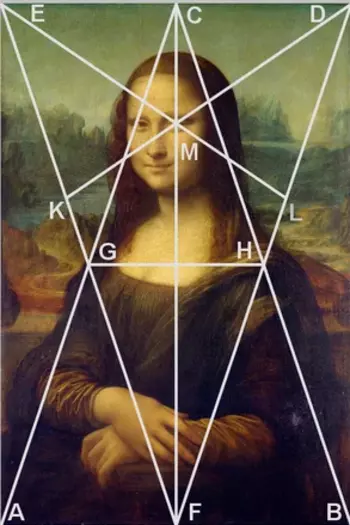

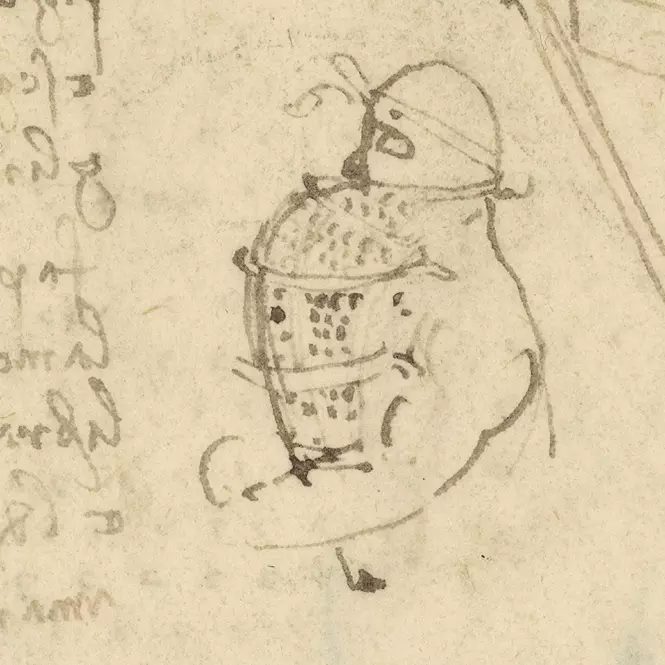

The sketch is often used to connect the eye of the Mona Lisa with the golden ratio.The lines KM and ML are supposed to form the two upper sides of a pentagon, the triangles EKM and DML on top of them two of the five points of a pentagram.KD and KM would then be in the ratio of the golden ratio.However, the sketch is incorrect.The angles are inaccurate and drawn with too broad a line.They deviate from the correct angles by 0.5° and 1.5° respectively

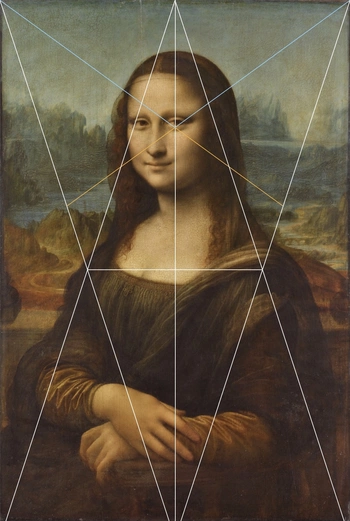

The right eye of the Mona Lisa is actually important in terms of the composition of the picture.The iris of the eye is located vertically exactly in the center of the picture (red line).If the painting is divided in height according to the golden ratio, both column feet are exactly at this height (left strip).If the larger section created in this way is divided again in the golden ratio (continuous division, right-hand stripe), the new golden ratio runs exactly through Mona Lisa's eyes

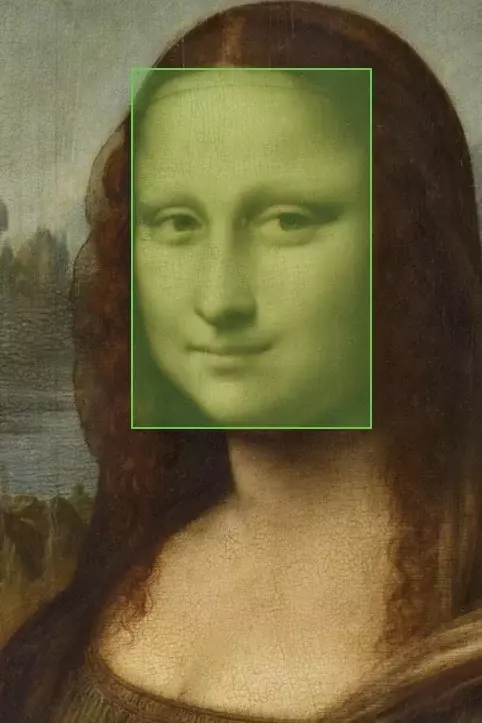

Does Mona Lisa's gaze follow the viewer?

Many who look at the portrait have the feeling that the Mona Lisa's gaze is following them. However, on closer inspection of the eyes, the Mona Lisa is not looking directly ahead, but slightly to the right, past them. Basically, the direction of the eye's gaze is determined by the position of the iris and the pupil. If they are at the right edge of the eye, a person looks past the observer on the right, as they do if they are at the left edge of the eye. Only if the iris is in the middle of the front of the spherical eyeball does the person look directly forward and thus at the observer.

The smile of the Mona Lisa

The Mona Lisa's smile is the most studied subject of the painting in terms of art history. It has already become clear by this point that Leonardo has condensed many different aspects into numerous details to create a wonderful painting. Mona Lisa's smile is just another - albeit the best known - of these details. It changes its meaning depending on the context and the viewer's level of knowledge and therefore cannot be clearly interpreted. What is clearer, however, is the optical trick Leonardo used.

Instead of physically increasing the distance to the image, observing eyes can also change the focus, e.g. by alternately looking at Lisa's head as a whole and then only at her mouth

Is the Mona Lisa a self-portrait?

The Mona Lisa could be a hidden self-portrait by Leonardo for two reasons. Anagrams to the Mona Lisa (swapping the order of the letters) support this. "Mon Salai" (French 'My Salai') refers to Leonardo's pupil Salai. "Mon Alias" (French for "my pseudonym") or "Nom Alias" (French for "alias name") are also possible. However, Leonardo never called the painting Mona Lisa. According to Salai's will, it was originally called "Gioconda" (Italian 'the cheerful one', French 'Jaconde') in Leonardo's circle.

Some claim to see a bearded Mona Lisa when looking at the painting for a long time and interpret it as a self-portrait of Leonardo. This is based on an optical illusion. The portrait of the Mona Lisa is designed in such a way that large dark areas have been painted around the very light face. Together with the strikingly light décolleté, they frame the largest light area. Fixing on a point in the painting produces an effect that is called an afterimage in the physiology of perception. This is a hallucination created by the human eye that produces a negative image, as is known from analog photography. The light spot of the décolleté appears in the negative image like a neatly trimmed dark beard. It is further emphasized by the dark shading in the chin area. However, the claim that the painting is a self-portrait of Leonardo is dubious, as no portrait of Leonardo is known to date that demonstrably shows him.

Theft and vandalism

- The Mona Lisa was stolen in 1911 by a worker who was glazing various paintings in the Louvre. Two years after the crime, the thief was caught in a fake money transfer and the Mona Lisa was returned to the Louvre in 1913. The painter Picasso was interrogated by the police for a time because he had unknowingly acquired works of art stolen from the Louvre and was therefore suspected of having commissioned the theft of the Mona Lisa. After the stolen works were returned, the matter was not pursued any further

- The painting has been the target of repeated attacks. In this order, it has already been pelted with a stone, showered with acid, rained on by a sprinkler system for a night and smeared with a cake. Since the acid attack, it has been behind bulletproof glass

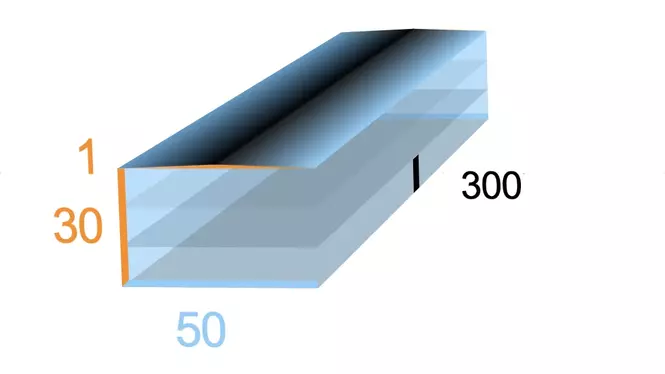

Painting is divided into two main parts.The first is form, i.e. the line that delimits the shape of the bodies and their details.The second is color, which is contained within these boundaries.

The line width corresponds to 1 mm in the original painting (desktop)

Mona Lisa

Leonardo da Vinci

1503-1519

Oil on wood (poplar)

53,4 x 79,4 cm

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Who was the Mona Lisa?

The identity of the Mona Lisa has not yet been established beyond doubt. However, the majority of researchers assume that it is Lisa del Gicondo, born Lisa Gherardini.

What makes the identification of the Mona Lisa so difficult is the fact that no commission documents, contracts, invoices or similar exist for the portrait. Leonardo da Vinci did not mention the painting in his notes, nor are there any clear descriptions from contemporary witnesses.

Theory I – Lisa del Giocondo

The majority of Leonardo scholars consider the sitter to be Lisa del Giocondo. All the arguments that support this thesis are now listed.

Was there a Mona Lisa?

Lisa di Antonmaria Noldo Gherardini is a historically documented person and was a Florentine noblewoman. Despite extensive research on her, little is known about her life today.

The Gherardini Family

The Gherardini family was an established Florentine family. Much of their once extensive land holdings were lost due to political missteps. Their ancestral castle was destroyed around 1300, leaving only the foundations. Nevertheless, they were not impoverished. They moved to the Villa Gherardini, a castle-like vineyard, which they developed into the family seat over the following centuries.

The Villa, located about 20 km southeast of Florence in the Chianti region, is now known as Villa Vignamaggio, a popular tourist attraction. It houses a restaurant ('Monna Lisa') and hosts wine tastings and weddings. Leonardo may have been inspired by a loggia of the Villa and used it as a reference for the background in the portrait of the Mona Lisa. A loggia is an open balcony, usually with small columns supporting a roof.

Despite political setbacks, the Gherardini family remained influential, maintaining close ties with Florence's most important families. Lisa's father, Antonmaria Gherardini, was wealthy and owned a centrally located townhouse in Florence and an estate in San Donato in Poggio, near the Villa Gherardini. He had married Camilla, a daughter of the significant Ruccelai family, creating ties to the influential Medici family through marriage.

Who was Lisa Gherardini?

Lisa Gherardini was born in 1479. At the age of sixteen, in 1495, she married Francesco del Giocondo, a wealthy cloth merchant from Florence. Francesco, 30 years old at the time, had previously been married to Camilla, Lisa's stepmother's sister, who died young. Francesco and Lisa had six children, with one daughter dying shortly after birth in 1499.

After the birth of their second child on December 12, 1502, they moved into a townhouse on Via della Stufa in Florence in March 1503. The house, located near the Medici Palace, showcased Francesco's economic success. Because such a move was a typical reason for commissioning a portrait at the time, most researchers believe that the portrait of the Mona Lisa began around 1503. Given that Leonardo's father knew Francesco del Giocondo since 1497, it is likely that he facilitated the commission to Leonardo.

During that period, it was common for affluent city dwellers to retreat to the countryside in the hot summer months. The del Giocondos also owned the Villa Antinori, a magnificent property on the outskirts of Florence. A loggia from this building is also considered as a possible background for Leonardo's portrait of the Mona Lisa.

After her husband's death in 1538, Lisa Gherardini entered the convent of Saint Ursula in Florence. She passed away there on July 15, 1542, at the age of 63.

Painted on commission from Francesco del Giocondo (after Vasari)

Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) was a renowned architect and painter in Florence. Thanks to his artist biographies published in 1550, he is also considered the first art historian. The work includes a much-quoted account of the life of Leonardo da Vinci, who had passed away 30 years prior. Vasari mentions the Mona Lisa:

"Leonardo also began to paint the portrait of Mona Lisa, the wife of Francesco del Giocondo. He spent four years on it, then left it unfinished, and it is now in the possession of King Francis of France at Fontainebleau.

Anyone who wanted to see how far art could imitate nature recognized it in this beautiful head. Every small detail was depicted in the finest manner, the eyes had brightness and moisture, as we see in life, all around one noticed the reddish-blue circles and veins, which can only be executed with the greatest delicacy. At the brows, you could see where they were fullest, where they were sparse, how they emerged from the pores of the skin and arched, as naturally as one can think. On the nose, the delicate openings were rosy and faithfully reproduced. The mouth, where the lips close and the red blends with the color of the face, had a perfection that made it appear not painted, but truly like flesh and blood. Whoever looked closely at the hollow of the neck believed to see the pulsating of the veins.

In short, one can say that this painting was executed in a way that made every excellent artist and everyone who saw it tremble. Mona Lisa was very beautiful, and Leonardo needed the precaution that, while he was painting, there always had to be someone present who sang, played, and made jokes so that she would remain cheerful and not acquire a sad look, as often happens when one sits to have their portrait painted. Above this face, however, hovers such a lovely smile that it seemed to be more from a heavenly than a human hand; and it was considered admirable because it was completely lifelike."

Vasari refers to Lisa del Giocondo as "Mona Lisa." "Mona" is an Old Italian abbreviation for the address Madonna ('My Lady'). Vasari's praise for the painting of the Mona Lisa's eyebrows indicates that he did not see the painting himself, as the Mona Lisa does not have eyebrows.

Historians Kemp and Zöllner have been able to demonstrate that Vasari was acquainted with two cousins of Francesco del Giocondo. Therefore, it is likely that Vasari could have personally met the older couple del Giocondo, as Lisa del Giocondo lived until 1542. Additionally, Vasari grew up under the care of the Medici family and was educated alongside their children. The Medicis were well-connected in Florence, familiar with Leonardo, and, moreover, distantly related to Mona Lisa's mother. It is likely that Vasari knew that Leonardo created a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo. However, Vasari tends to create legends, and his statements do not always align with the findings of art historians. It is also often unclear which of his statements are based on hearsay, meaning he lacked sufficient sources.

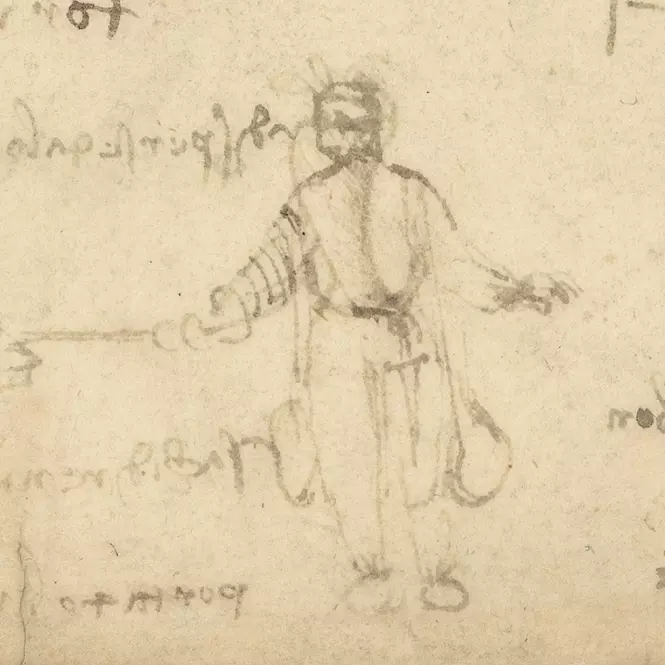

Maccari was inspired by Vasari's story. It is part of Vasari's legend that Leonardo had the Mona Lisa lavishly entertained while he painted her. In fact, the sitters of the time did not sit for hours on end. It was customary for professional painters to make a rough, yet faithful sketch of the sitter once and then use it as a template for the later painting. Characteristics of the final painting, such as a particular smile, hairstyle, pieces of jewelry, etc. were thought up by the artists or added separately based on models

Painted by order of Giuliano de Medici (after de Beatis)

Although the portrait of the Mona Lisa is said to have been commissioned by her husband Francesco, the painting was never in the possession of the del Giocondos. It is possible that it was not Francesco but Giuliano de Medici who commissioned the painting, as reported by a contemporary source.

During Leonardo's last three years, when he lived at the French royal court in Amboise, he was visited in 1517 by a delegation from Cardinal Luigi d'Aragona. The cardinal's scribe, Antonio de Beatis, wrote a report on the visit. This last eyewitness account is of great importance in Leonardo research as it mentions other paintings that de Beatis saw in Leonardo's workshop.

"In one of the districts, my lord and the rest of us went to see the Florentine Leonardo da Vinci, more than 70 years old [Here the scribe is mistaken; Leonardo was only 65 at the time], an outstanding painter of our time, who showed his illustrious lordship three paintings: one of a certain Florentine lady, a very beautiful painting made at the request of the Magnificent Giuliano de Medici; the second of a young John the Baptist, and one of the Madonna and her son, who are placed in the lap of Saint Anne, all very perfect, ..."

The "certain Florentine lady" most likely refers to the Mona Lisa. Lisa Gherardini's family was indirectly connected to the Medicis through marriage. The Florentine youths Giuliano de Medici and Lisa Gherardini were of the same age and grew up in close proximity. Due to the familial connection, it is highly likely that they knew each other, and there is speculation that Giuliano fell in love with Lisa.

However, the Medicis were expelled from Florence in 1494 and could only return in 1512. The 15-year-old Giuliano had to leave the city and spent many years in exile at the court of the Duke of Urbino. One year after the Medicis' expulsion from Florence, Lisa Gherardini married the wealthy merchant Francesco del Giocondo.

Leonardo had been living in Milan since around 1482 and returned to Florence only in 1503 for a few years. According to the theory, the exiled Giuliano de' Medici asked Leonardo to create a portrait of the now-married Lisa del Giocondo for sentimental reasons. This would explain why the painting was never in the possession of the del Giocondos.

Giuliano de Medici was the brother of Pope Leo X (1513-1521) and an admirer of Leonardo. At Giuliano's request, Leonardo stayed at the papal court in Rome from 1513 to 1516. When Giuliano unexpectedly died in 1516, Leonardo left Rome and went to France. De Beatis's report indicates that he had the portrait of a certain Florentine lady with him, made at the request of Giuliano de Medici. Therefore, Leonardo may not have been able to hand over the Mona Lisa to Giuliano because the painting was still unfinished, or he took back the completed work after Giuliano's death.

This theory is speculative, and the only evidence is Beatis's mention of the certain Florentine lady commissioned by Giuliano de Medici.

In the background the Castel Sant'Angelo, a refuge in the Vatican, Rome

Giovanni was the older brother of Giuliano

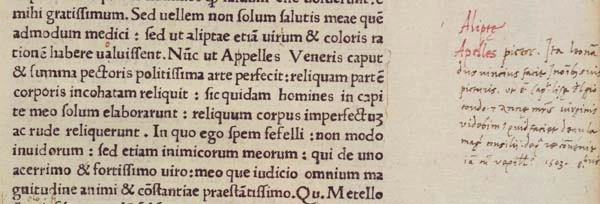

The Heidelberg Note

A source published in 2005 proves that Leonardo worked on the portrait of Lisa del Giocondo.

A book about the ancient politician and writer Cicero, which was printed in 1477, was found in the Heidelberg University Archive (shelfmark D 7620 qt. INC). It has been proven that the book belonged to one Agostino Vespucci. Vespucci was a scribe and close collaborator of the famous Florentine politician Niccolo Macchiavelli. At the time, Macchiavelli supported Leonardo with commissions from the Florentine city government. It was probably at his instigation that Leonardo was commissioned to paint the huge mural "Battle of Anghiari". For this purpose, Vespucci translated a description of the battle from Latin, which is still preserved today, and gave it to Leonardo. Vespucci and Leonardo therefore knew each other well, which increases the credibility of the source.

Agostino Vespucci left a short handwritten note in the book in which he praised Leonardo's painting and mentioned that he was currently working on a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo. The note also confirms Leonardo's work on the paintings "Anna Selbdritt" and "Battle of Anghiari" for the Council Chamber of Palazzo Vecchio. This note is considered an important document in the history of the Mona Lisa's creation, even if the authenticity of the note can hardly be proven.

The play on words with Lisa del Giocondo's surname

In the Renaissance, wordplay was very popular, and Leonardo da Vinci had a particular fondness for it.

His famous portrait of the lady with an ermine features Cecilia Gallerani. The ermine belongs to the weasel family, and the Ancient Greek word for weasel is "galê" or "galéē."

Another portrait depicts the lady Ginevra de' Benci. She is seated in front of a juniper tree. "Juniper" translates to "Ginepro" in Italian.

Leonardo's preference for wordplay also supports the identification of the lady as Lisa del Giocondo. The most noticeable feature of the painting is her cheerful expression. "Gioconda" is the Italian word for "the Cheerful," and it is assumed that her joyous smile alludes to her surname "del Giocondo."

Salai's Estate

Salai was one of Leonardo's longest-serving collaborators and was named as one of Leonardo's heirs in his will. A few years after Leonardo's death in 1519, Salai died unexpectedly in a duel in 1524. Following his death, his wife and sisters disputed his estate. A document has been preserved, revealing that Salai owned a painting referred to as "La Joconda," described briefly as "a woman turned backward."

Even today, the Mona Lisa is referred to as "La Joconda" or "La Joconde" in France. "La Joconde" was originally not a French term but is derived from the Italian "Gioconda." This designation from Salai's estate links that particular portrait with the surname of the Florentine lady Lisa del Giocondo.

The value of Salai's "La Joconda" was set by the notary at 100 Scudi (= 175 Florins = 612.5 Gold). For the time, this was a considerable sum, strongly suggesting that Salai's "La Joconda" was an original painting by Leonardo. If so, it could only be Leonardo's portrait of Lisa del Giocondo.

Theory II – Pacifica Brandani

In addition to the identification of the Mona Lisa as Lisa del Giocondo, a few researchers propose the idea that it could be a portrait of Pacifica Brandani. Since the hypothesis is internally consistent, it should not go unmentioned.

The starting point for this theory is the well-known travel report from de Beatis in 1517, which stated "[...] one of a certain Florentine lady, a very beautiful painting made at the request of the Magnificent Giuliano de Medici."

Giuliano's biography includes the tragic fate of his only son, Ippolito. When Giuliano was in exile, he had an affair with the court lady Pacifica Brandani at the court of Urbino. She became pregnant but died in 1511 during the birth of their son, Ippolito. Since Ippolito could not know his mother, Giuliano is said to have commissioned from Leonardo a painting of an idealized, cheerful mother figure. The painting was intended to console young Ippolito over the loss of his mother. Therefore, the portrait is said to have been named La Gioconda (Italian for "the Cheerful").

However, according to the theory, Ippolito did not receive the painting. When his father Giuliano died in 1516, Leonardo is believed to have retained the still unfinished painting when he left for the French court in 1516. While this narrative seems plausible, it relies solely on the remark "at the request of the Magnificent Giuliano de Medici" in de Beatis's travel report.

Modern findings

The most significant discovery related to the identity of the Mona Lisa was made by the French physicist Pascal Cotte. He developed an innovative physical method to reconstruct the chronological order of paint layers in paintings. The Louvre granted him the rare permission to examine the original painting between 2004 and 2015. Surprisingly, he found that beneath the portrait of the Mona Lisa, there is an earlier portrait depicting a significantly younger lady. The current Mona Lisa is, therefore, the result of overpainting. The earlier portrait is largely identical in position and overall composition but differs significantly in hairstyle, face, and shoulder area.

@Pascal Cotte / Lumiere Technology

The painting exhibits many parallels to the original version of the Mona Lisa: posture, shoulder area, sleeve folds, backward-directed hairstyle, the wall with protruding columns, the landscape in the background, and the overlapping hands. The unicorn likely references Leonardo's legendary court festivities, where he elaborately costumed animals and let them roam freely

The posture of the hands lying on the chair back is clearly related to Leonardo's Mona Lisa. The dynamically twisted sitting posture of Leonardo's Mona Lisa was so innovative that it cannot be a mere coincidence. Another indication of imitation is the transparent veil over her shoulders

This painting is also very similar to Leonardo's Mona Lisa. It portrays the same pose and likewise features a transparent veil over her shoulders

Result of Pascal Cotte's examination

The result of Pascal Cotte's examination clarifies significant open questions related to the Mona Lisa. Vasari describes the finely painted eyebrows of the Mona Lisa, even though she obviously has none. He must have relied on accounts he heard about the first version of the Mona Lisa. He likely never saw the original painting himself, as it was at the French court in Fontainebleau during his lifetime, as he himself reports.

Pascal Cotte's findings also explain the striking similarity of three portraits by Raphael to that of the Mona Lisa. They undoubtedly originated around the same time. Raphael was in Florence between 1504 and 1505, the period when the Mona Lisa was started. The younger Raphael knew Leonardo personally and imitated his style in many of his works. It is very likely that Raphael saw the portrait of Lisa del Giocondo in Leonardo's workshop. It must have been the version revealed in Pascal Cotte's examination because that's the only way to explain why Raphael's portraits closely resemble Leonardo's Mona Lisa but differ significantly from the present version. Raphael must have seen an earlier version of the Mona Lisa, precisely the one Pascal Cotte identified.

Conclusion

The extensive copies by Raphael and the analysis by Pascal Cotte now lead to a straightforward conclusion, consistent with all previous findings.

In 1503, Leonardo received the commission in Florence to paint Lisa del Giocondo. The commission either came from her husband, Francesco del Giocondo, through the mediation of Leonardo's father, or from the infatuated Giuliano de' Medici in exile in Urbino. Leonardo began the portrait but left it unfinished. At that time, the painting looked as Pascal Cotte discovered. Raphael must have seen the unfinished work between 1504 and 1505 in Leonardo's workshop and imitated this Mona Lisa in at least three portraits. When Leonardo left Florence for the second time in 1508 and returned to Milan, four years of unfinished work on the portrait, mentioned by Vasari, had passed.

After 1508, Leonardo must have extensively revised the work until it took its present form. This supports the theory that in this second version, Leonardo no longer had Lisa del Giocondo in mind but probably created an idealized female figure. Whether this happened after 1511 and again on the commission of Giuliano de' Medici, following the Pacifica Brandani theory, to give his grieving son a comforting image of a mother, or whether Leonardo revised the work on his own initiative, remains unclear. Overall, this is currently the simplest explanation for the history of the creation of the Mona Lisa.

This does not rule out the possibility that contemporaneously with Leonardo's work on the painting, there were copies by students in his workshop. However, when objectively considering their painterly quality, these copies do not match Leonardo's Mona Lisa and are evidently imitations. They demonstrate how challenging it is for painters to imitate Leonardo's style.

The painting most likely originated in parallel with the Mona Lisa, as some overpaintings are exactly the same. Judging by the color palette, it is presumably a work of Leonardo's student Francesco Melzi

The painting is done on canvas. However, Leonardo always painted on wooden panels. The style is also atypical for Leonardo

Creation time and owner

Leonardo's life around 1503

When Leonardo began the portrait of the Mona Lisa in 1503, he was approximately 50 years old. Born and raised in Florence, he had been living in Milan since the age of 30. After completing "The Last Supper" in 1498, he was considered the greatest living artist. However, when the Duke of Milan was expelled by the French the following year, turbulent times began for Leonardo. He fled the war, sought new patrons in northern Italy, but eventually returned to Florence in the summer of 1500. Around 1501, he started the large-scale painting "The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne" and the "Madonna of the Yarnwinder" for a French court official. Influenced by his collaboration with the mathematician Luca Pacioli, he delved into mathematical studies during this time.

A study for the painting likely created around 1508, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne

The work of a student of Leonardo was created for Florimond I. Robertet, one of the most influential financial officials of the French king

Leonardo likely worked on this painting simultaneously with the Mona Lisa. Both paintings remained in his possession until his last years

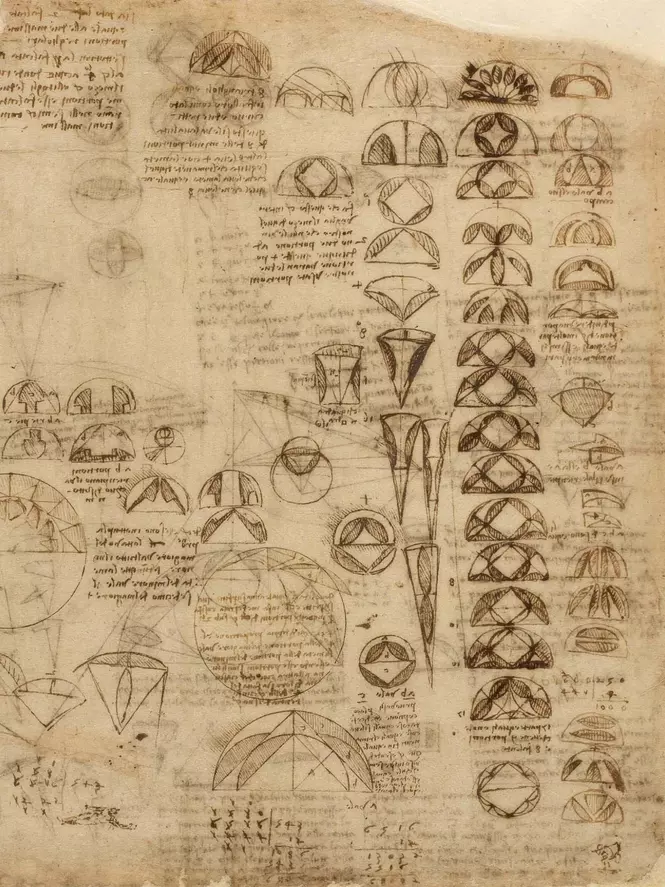

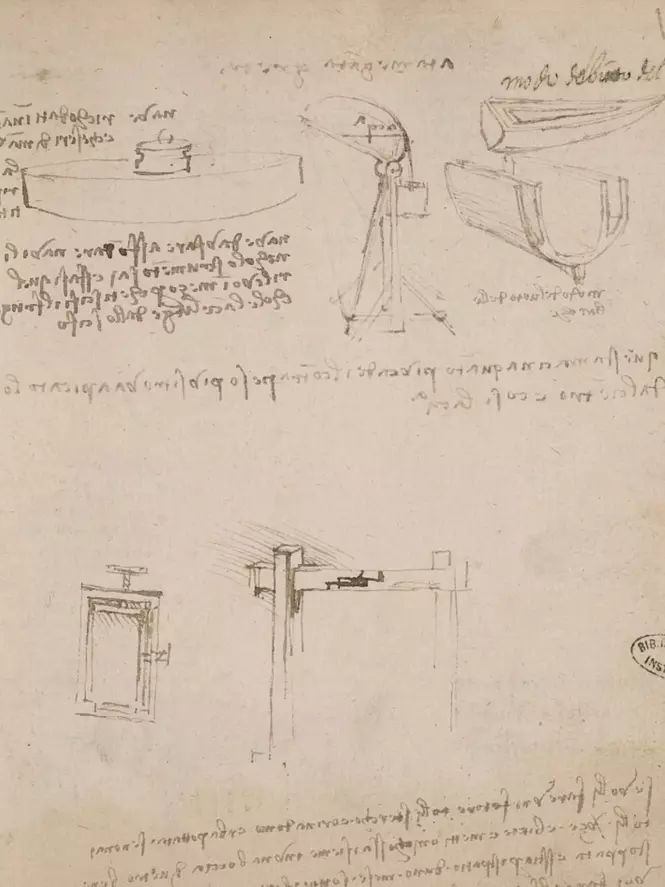

The sheet examines the equality of areas in a circle divided according to integer proportions

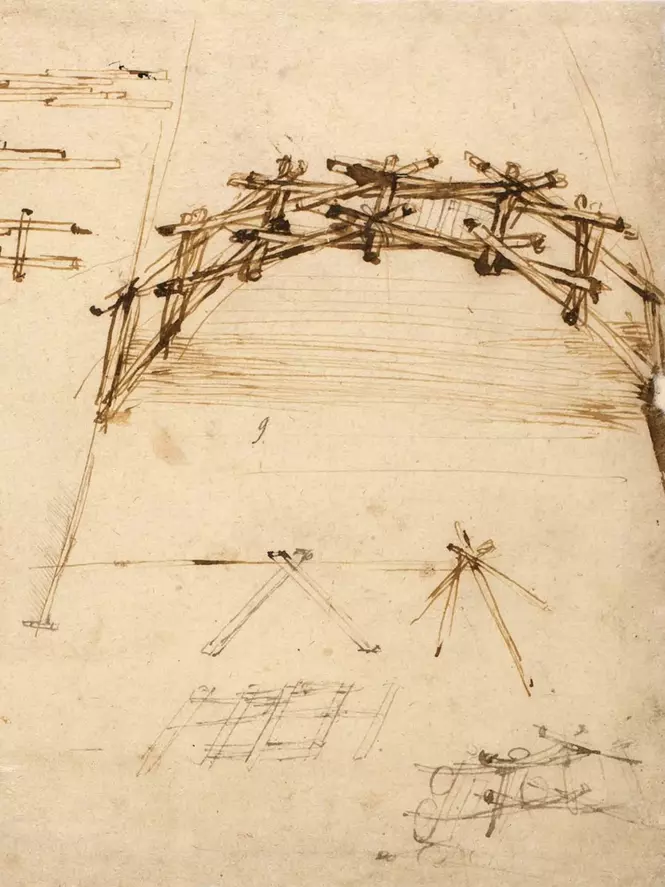

The bridge is self-supporting and consists of individual loose tree trunks that need to be simply laid on top of each other, requiring no ropes or nails. Leonardo employed it when accompanying Cesare Borgia on a military campaign, and the troops needed to cross a river

The Borgia campaign and the Battle of Anghiari

In the summer of 1502 until spring 1503, Leonardo accompanied Cesare Borgia, the son of the Pope, as a military engineer. Upon his return to Florence, he started the portrait of the Mona Lisa. In 1504, his father died, and Leonardo's illegitimate son was excluded from the inheritance. In the same year, he received the commission for his second major fresco, the "Battle of Anghiari," for the city parliament of Florence. The younger painter Michelangelo was to create an equally large painting on the opposite wall simultaneously, initiating a competition between the two artists. However, due to wet walls, the work progressed slowly and was eventually abandoned. In 1504, Raphael also came to Florence and painted portraits in the style of the Mona Lisa, inspired by Leonardo's painting.

The painting was intended to be over 4 meters in height, larger than Leonardo's Last Supper. However, the battle painting was never completed

The battle painting was on the opposite wall and also remained unfinished

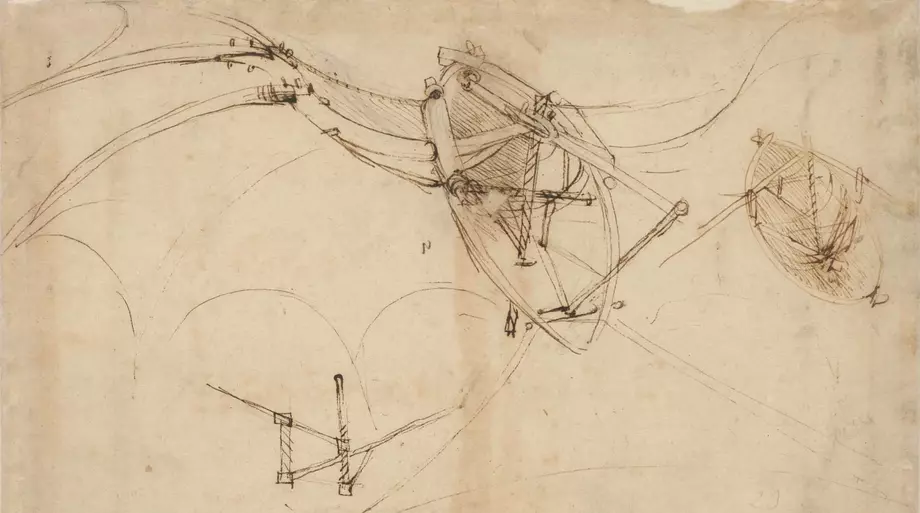

Leonardo's flight experiments on the Schwanenberg

Leonardo undertook flight experiments on the Schwanenberg near Florence around 1505. They coincide with the time when the Mona Lisa was painted.

Leonardo's analogy-based thinking is evident in the shape of the hull, reminiscent of a boat. He likely considered applying the principles of aviation to his underwater vessels, or vice versa

Return to Milan

From 1506, he commuted between Florence and Milan, and by 1508, he was living in Milan again. The portrait of Mona Lisa likely had less significance until then, as Leonardo focused on more prestigious commissions. Vasari claims it was still unfinished in 1508, and it probably received its final form after that year. According to de Beatis, the painting accompanied Leonardo to France in 1516 and remained there until his death in 1519 at Château du Clos Lucé.

Fate after Leonardo's death

It is unclear what happened to the paintings that de Beatis saw with Leonardo. Leonardo's will does not mention any paintings, but it does include bequests to two of his pupils. Francesco Melzi received Leonardo's significant notebooks, other books, equipment, clothes, and gold. On the other hand, Salai received a property in Milan, which he had already leased from Leonardo. Salai's will indicates that he likely owned some of Leonardo's paintings.

Salai's Will

Salai died in 1524 at the age of about 44 in a duel, just a few years after Leonardo's death. His sisters and his widow subsequently contested the inheritance, which mainly consisted of valuable paintings. The notarial records list a painting titled "La Joconda," and since it is relatively highly valued in the document at 100 Scudo (175 Florin = 612.5 Gold), it is likely the Mona Lisa. Shortly thereafter, the French King Francis I must have acquired the painting.

Salai's Sale of Paintings

In 1999, French art historian Bertrand Jestaz published an essay about a rediscovered sales contract. He explains that the painting currently housed in the Louvre ended up in the royal collections in 1518 as part of a sale of some of Salai's paintings to King Francis I. The king paid Salai about 2604 Livres (approximately 651 Florin = 2.3 kg Gold), "for certain panel paintings that he gave to the king." Therefore, it is widely believed today that Leonardo gave the still unfinished paintings, including the Mona Lisa, to Salai about a year before he died. The paintings listed in Salai's will are presumed to be copies made by Salai.

In the Possession of French Kings

The exact circumstances of how the painting came into the possession of the French king remain uncertain to this day. However, Vasari reported in 1550 that the Mona Lisa was now at Fontainebleau Castle, an important hunting lodge of Francis I. The painting remained there until Louis XIV had it moved to Versailles around 1682.

The French Revolution and Napoleon's Bedroom

During the French Revolution in 1789, all paintings from the royal collection were transferred to the Louvre, and in 1793, the Mona Lisa was publicly exhibited for the first time.

The painting may have remained there for only a few years because there is a legend that Napoleon had the painting brought to his bedroom in the Tuileries Palace around 1799. According to the legend, the portrait hung there until his exile in 1815. The Mona Lisa has been publicly displayed in the Louvre since at least 1815.

According to legend, the Mona Lisa is said to have been in Napoleon's bedroom

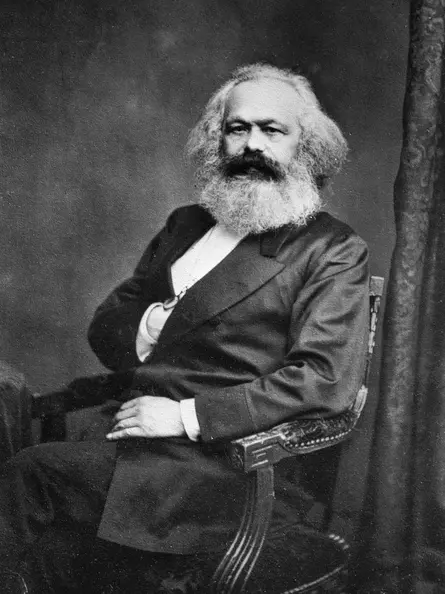

In this famous photograph, Karl Marx imitates both the posture of the Mona Lisa and the hand gesture particularly associated with Napoleon. Karl Marx founded the philosophical school of communism

The Theft of 1911

The Mona Lisa was stolen on August 21, 1911, by the Italian Vincenzo Peruggia in a sensational act from the Louvre.

The Louvre Museum, fearing vandalism, had decided to secure all paintings behind a glass barrier by 1911. Peruggia was one of the glaziers involved in this project. Due to his work at the museum, he was well-known to the staff and familiar with the premises.

On the day of the theft, a Monday when the Louvre was closed to the public, Peruggia entered the building in his work clothes, blending in with the staff. He went to the Mona Lisa and took advantage of an unobserved moment to remove the painting, initially placing it in a staircase where he took it out of the frame. The Mona Lisa, painted on a wooden panel, is relatively small (53 × 77cm), making it easy for Peruggia to conceal. He might have hidden it under his smock or wrapped it up, carrying it like a sheet of glass. Then he left the Louvre. The theft was only noticed the following day when a painter, who had been copying the Mona Lisa for some time, inquired about the painting.

Peruggia viewed the theft as a patriotic act, intending to bring the painting to Italy, Leonardo da Vinci's homeland. The theft remained unsolved for two years. It was only when Peruggia attempted to sell the painting to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence that he was arrested during the planned handover. The painting was exhibited in several Italian cities for a few months before returning to the Louvre on December 31, 1913.

Picasso and the Theft of the Mona Lisa

For a while, the Spanish painter Pablo Picasso and his circle were suspected of being involved in the theft. Picasso lived in Paris at the time and was acquainted with Géry Pieret through his friend, the poet Apollinaire. Apollinaire and Pieret were friends, sometimes living together. Pieret was an occasional thief who stole valuable sculptures from the then barely secured Louvre and sold at least two of them to Apollinaire in 1907, who then passed them on to Picasso. Shortly after the theft of the Mona Lisa, Picasso returned the two sculptures and was questioned by the police, while Apollinaire was even arrested for two days. They were accused of being part of an international theft ring. Picasso was not charged further after the interrogation, and Apollinaire was acquitted in a subsequent trial due to a lack of evidence.

World War II

During World War II, France was occupied by Germany. Before the Germans took Paris, the Louvre, fearing theft or damage, conducted an elaborate operation to transport almost the entire art collection anonymously and sealed to Château de Chambord. The Mona Lisa was in an inconspicuous crate. During the war, the valuable painting was moved several times to different locations in France without falling into the possession of the German occupiers.

The entire art collection of the Louvre was transferred to Chambord at the start of the war.

Chambord is the most significant Renaissance castle in Europe. The design of the castle is attributed to Leonardo. At the center of the main building is a unique double-helix staircase

Modern

With the end of the war, the Mona Lisa was able to return to the Louvre, where it was publicly displayed again from October 1947.

Vandalism

In 1956, an unknown individual poured acid on the painting, causing severe damage to the lower part of the image. In the same year, a visitor threw a stone at the painting, damaging the left elbow of the figure. Since then, the Mona Lisa has been behind bulletproof glass.

The Mona Lisa in the USA

In 1961, Jacqueline Kennedy, the wife of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, persuaded the then French President Charles de Gaulle to exhibit the painting in the United States. In an elaborate operation, the painting was transported across the Atlantic in January 1963 under tight security and exhibited at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and shortly afterward at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The then-director of the museum, Thomas Hoving, wrote in his memoirs that the Mona Lisa was exposed to flowing water from an accidentally triggered sprinkler system overnight during the exhibition. However, since the painting was behind water-resistant bulletproof glass, the Mona Lisa remained undamaged.

The Mona Lisa in Japan and Russia

In 1974, there was a second international exhibition in Tokyo and Moscow.

Vandalism

In 2022, a visitor attempted to shatter the bulletproof glass of the Mona Lisa. As expected, he failed, but he smeared the glass with a cream pie. To approach the painting, he had disguised himself as a woman and sat in a wheelchair. He claimed that his motive was to draw attention to the environment.

Public exhibition at the Louvre in Paris

The painting is currently displayed in the largest hall of the Louvre in Paris, the Salle des États.

Image analysis

The leading art historian and Leonardo expert Martin Kemp (Oxford, Harvard, Princeton) associates the Mona Lisa, specifically the right background of the painting, with the depiction of a deluge. This image analysis follows and elaborates on this view, recognizing the motif of water as the connecting element in the background.

This perspective is justified by the interplay of trompe-l'oeil effects and complex yet clear geometric relationships of high symbolic value existing among prominent elements of the painting. After a general presentation of formal peculiarities of the painting, it becomes clear that Leonardo conceived the Mona Lisa closely tied to the motif of water and the hidden power within it. Correspondingly, symbolic connections are made to the two most famous floods. Firstly, Leonardo suggests a rearing water wave in the right background reminiscent of Noah's flood. He confirms the initially barely perceptible by using the proportions of Noah's Ark mentioned in the Bible for the lower third of the painting.

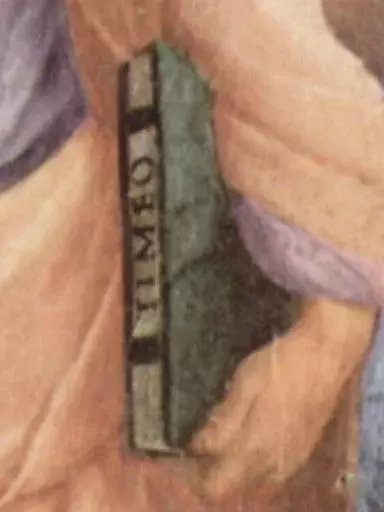

Secondly, the painting reveals a simple but complex system of geometric relationships that ultimately refer to the Platonic solids. They are first described in Plato's book Timaeus. This book talks about the legendary city of Atlantis and its downfall. For this second aspect, it will be shown how much Leonardo's persona was equated with that of Plato by contemporary artists. Additionally, how Leonardo uses geometric relationships between prominent elements in the painting to guide the viewer's gaze to her hands, only to ultimately focus on the Mona Lisa's left eye.

To clearly depict the geometric relationships that underpin these connections, the unframed version available on the Louvre's website was used for this analysis #.

Image Description

A lady in a three-quarter portrait is seated on a chair. The chair's back forms a semicircle, connected to the seat through small balusters, with five balusters visible.

The chair is oriented to the left, and the lady, through a slight rotation of hip, shoulder, and head, faces left towards the viewer. While doing so, she looks slightly past the viewer to something behind them, smiling.

Her hands are clasped one over the other on the left chairback. The left hand holds a brown blanket, draped over her legs. The index and middle fingers of the right hand are slightly spread.

She wears a dark green dress with orange sleeves, finely gathered into folds. The dark green part of the dress is turned up at the sleeves and fastened at the shoulder. The seam at the neckline is intricately embroidered with orange stitches. The dress falls in fine waves due to the gathered seam. Her neck and neckline are uncovered, and she wears no jewelry.

Her brown open hair cascades in fine curls from a center part down to her shoulders on both sides. Her hair is covered by a very long, nearly transparent veil. The veil is rolled down towards the bottom and hangs loosely over her left shoulder.

Directly behind her is a waist-high wall. At the left and right edges of the painting, the bases of two columns can be seen, placed on the wall.

In the background, a mountainous landscape with paths and waterways. In the right half of the painting, a bridge over a river.

The lower part of the painting (ceiling, chair, and wall), as well as large sections of the landscape, are unfinished.

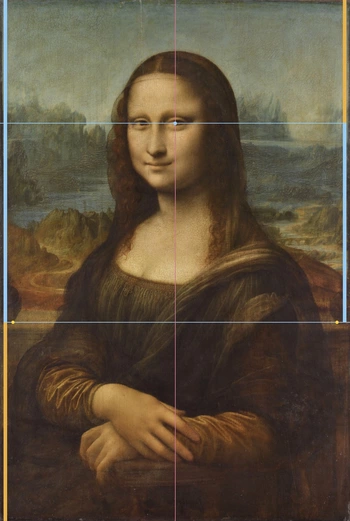

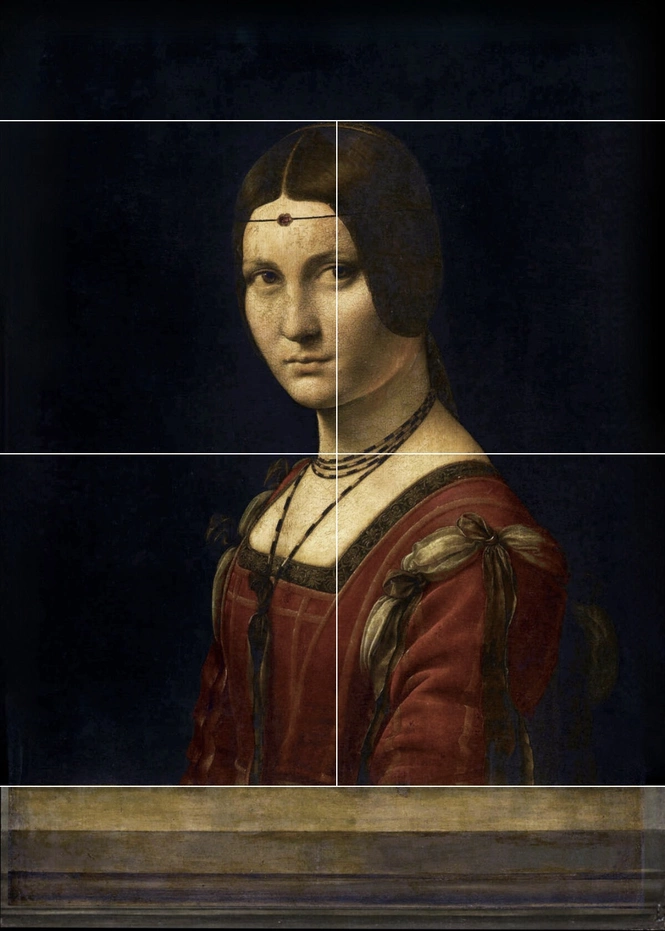

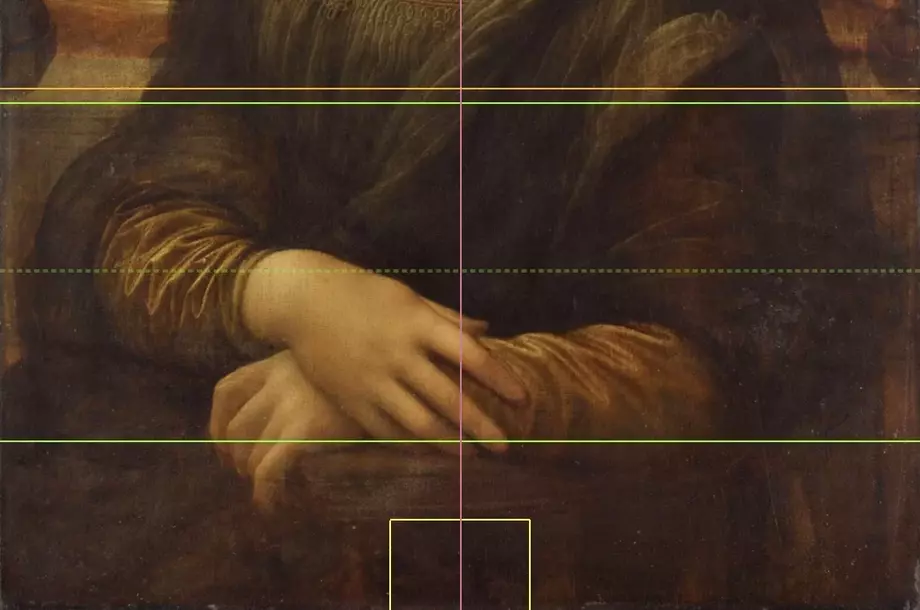

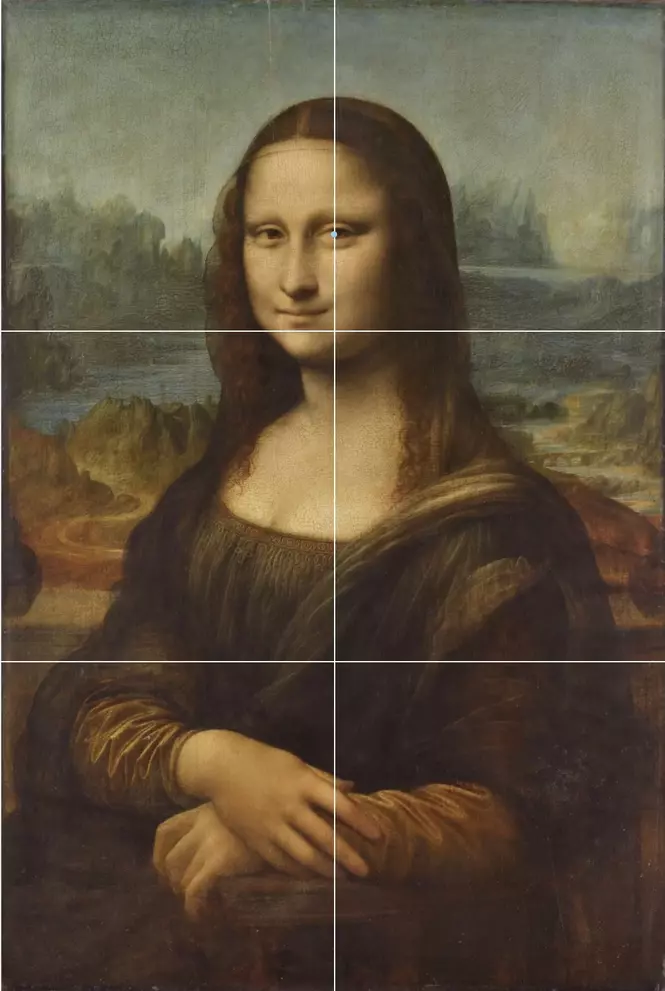

I The six quadrants

The outer dimensions of the portrait correspond quite closely to the ratio of 2:3. Therefore, the portrait can be divided into six approximately equal-sized squares.

The Mona Lisa as the conclusion of a three-part portrait series

The division of the paintings into prominently constructed squares is a recurring motif in Leonardo's three undeniably genuine female portraits. There is a clear connection between the number of squares and the timing of their creation:

| Around 1491 | Lady with an Ermine | 1 square |

| Around 1497 | La Belle Ferronière | 4 squares |

| Around 1503 | Mona Lisa | 6 squares |

The paintings also exhibit a certain chronology. Cecilia Gallerani (Lady with an Ermine) and Lucrezia Crivelli (La Belle Ferronière) were successively mistresses of the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, and each was the mother of an illegitimate child. Leonardo had worked for the Duke of Milan for approximately 12 years until 1499.

Lady with an Ermine is the simplest in terms of image construction and does not depict any architecture or landscape. In contrast, La Belle Ferronière introduces a wall into the painting, creating a separation between her and the viewers. Despite appearing initially unremarkable, upon closer examination of the composition, the painting reveals a rather complex interplay of harmonies. The subsequent portrait of the Mona Lisa repeats the motif of the wall and now introduces a landscape. The Mona Lisa is no longer behind a wall but in front of it, in a space with the viewers. Due to these non-random connections, it is reasonable to consider the three paintings as part of a series. The childlike Lady with an Ermine is followed by the portrait of a young adult, and with the Mona Lisa, a maternal figure is presented.

Leonardo's Emphasis on the Eyes

It is typical of Leonardo to emphasize one eye of the portrayed figure by placing it on one of the two classical divisions of the width of the painting: halving or the golden ratio. In the case of the Mona Lisa, the vertical midline of the portrait emphasizes her left eye I, as is also the case in the preceding painting La Belle Ferronière, but in contrast to the Lady with an Ermine.

The upper end of the square emphasizes the lady's eyes (red horizontal line). It aligns with the golden ratio of the image height (orange horizontal line), passing through the right eye of the ermine. The vertical midline and golden ratio of the image width each touch the left end of one of the lady's eyes (red and orange vertical lines)

La Belle Ferronière is within a square that, due to additional geometric relationships around her shoulder, can be further divided into four squares. In contrast to the earlier Lady with an Ermine but analogous to the subsequent Mona Lisa, the vertical midline passes through her left eye

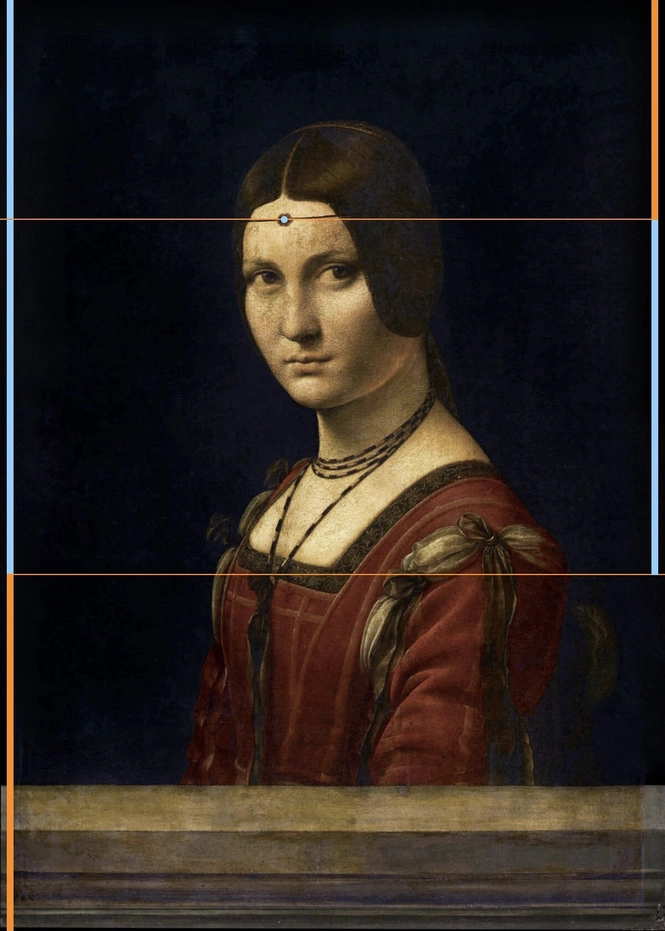

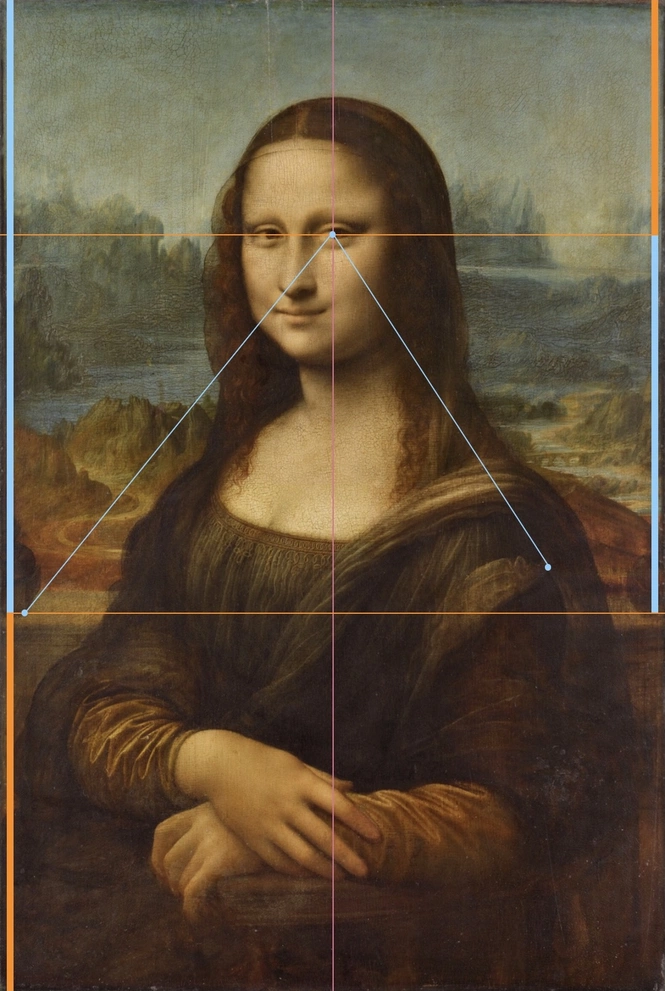

II Golden Ratio

Leonardo used the golden ratio to determine the position of the column bases and the eyes.

- The bases of the support columns on the wall are positioned at the golden ratio of the image height (lower orange line).

- The front edges of the column bases mark the width of a golden rectangle (blue transparent area).

- If the larger part of the golden ratio of the image height is again divided by the golden ratio, it now passes through the two eyes of the Mona Lisa (upper blue line).

Leonardo also applied the golden ratio in other paintings. In general, it is not uncommon to use the golden ratio as one of many proportions in art, even into modern times. Since the golden ratio is considered the most beautiful proportion due to its mathematical properties, it is often used to highlight a particular aspect of an artwork.

However, the Mona Lisa is the only one of the three undoubtedly authentic Leonardo portraits that emphasizes the left eye in the golden ratio of the image height. In the Lady with an Ermine, a division like that in the Mona Lisa misses the left eye and runs just above it, and in La Belle Ferronière, the jewel on the headband is emphasized instead of the eye.

The Madonna of the Rocks displays the golden ratio in a less complex form. More interesting is its integration into this altarpiece. It has the dimensions of a golden rectangle. Its diagonal leads to the right eye and the neck brooch of the Madonna. The eye of the young John on the left is in the golden ratio of the image height. A golden spiral leads to the eye of the infant Jesus. The spiral itself ends in darkness

The staging of the golden ratio anticipates that of the Mona Lisa, with the difference that here, it emphasizes the jewel on the headband rather than the eye. Additionally, the painting also features a wall, but in this case, it serves to create a boundary in the foreground. The Belle Ferroniere appears to, in Leonardo's eyes, value different aspects compared to the Mona Lisa, who, unusually for a noblewoman, wears no jewelry. The golden ratio often emphasizes a crucial visual element.

The potential continuations of the golden ratio

Additional subdivisions of the resulting segments in the golden ratio are possible (mouseover). However, they all miss significant elements in the painting: the upper end of the head is narrowly missed, the upper end of the shoulder is not precisely hit, and so on. Even when, for example, the tip of the nose or the end of the headscarf is hit below its central part, it is unclear whether this was Leonardo's intention. When Leonardo wants to clearly demonstrate the golden ratio, he does so very precisely, as evident in the feet of the columns and the eyes. Further subdivisions in the golden ratio according to the principle of continuous division appear to be merely coincidentally close to significant elements in the painting.

Golden Spiral

The edges of the column bases at the left and right edges of the painting form the borders of a golden rectangle, suggesting a golden spiral. Unlike the Grotto Madonna, Leonardo did not clearly position elements along the golden spiral.

The third, slightly smaller golden rectangle narrowly misses the pupil of Mona Lisa's right eye. Overall, the golden spiral clearly leads away from the face.

The fact that the golden spiral intersects with Mona Lisa's right hand appears coincidental. Similarly, the center of the spiral being below the blue horizontal line on the right side seems incidental

The interior of the spiral approximately intersects with Mona Lisa's right wrist and roughly follows her right arm. However, the head of Mona Lisa is noticeably imprecisely hit

Again, no clear intention of Leonardo can be discerned here, even though the head and the left hand are approximately tangential. Certainly, the golden spiral can be shifted, enlarged, and reduced to show any arbitrary alignment, but that would no longer align with Leonardo's intention

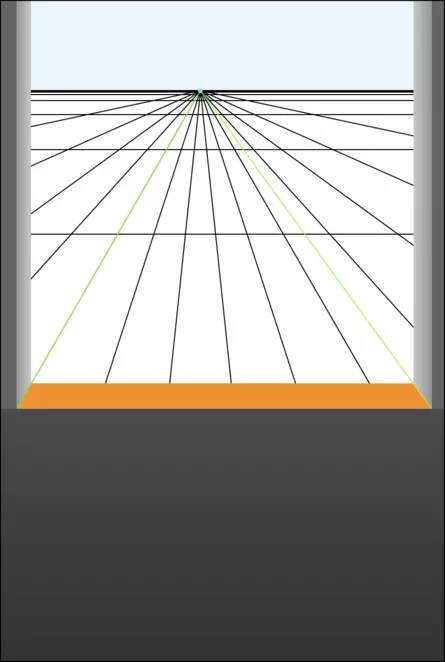

III The false perspectives

One of the peculiarities of the painting is the use of multiple perspectives, evident in several horizon lines. However, in reality, it is not possible to have multiple visible horizon lines at the same time. Either the background is a painted picture within the picture, similar to how early photographs show painted backdrops, or Leonardo has layered views of the landscape from different angles.

Frontal Representation of the Mona Lisa

The portrayed lady sits on a chair, facing the viewer directly. The viewer is at eye level with her, neither looking up nor down at her.

Central Perspective

An architectural vanishing point can be determined once at least two vanishing lines are drawn in the painting. The vanishing point of a central perspective always aligns with the horizon. Although the architecture in the painting is minimal, it is still present. The wall behind the Mona Lisa and the feet of the columns resting on it can be recognized as vanishing lines. The point where both vanishing lines meet is the vanishing point of the central perspective. This point lies precisely at the center of the Mona Lisa's hairline (white lines). This means that the viewer is looking at the wall from a relatively steep angle from above. However, this view contradicts the frontal depiction of the Mona Lisa's body.

The Blue Horizon

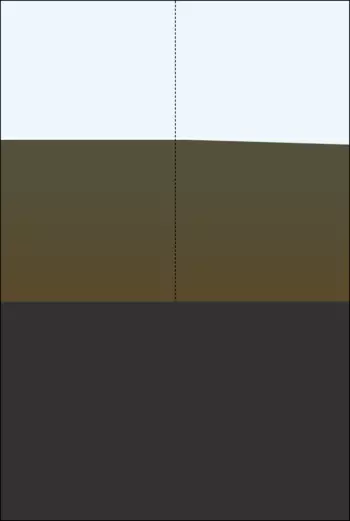

At first glance, the painting does not have a clear horizon line. Instead, it seems to have multiple ones.

The first painted horizon line is indicated by two horizontal light blue areas (blue line). On both sides, the horizon is concealed by mountains, but in the transparent veil of her hair, a very short horizontal line can be discerned to the right of her head. This line is at the same height as a horizontal light blue area (a lake or sea) at the left edge of the painting, as well as a larger light blue area at the same height in the right half of the painting (another lake or sea). This right area is inclined in a straight line to the lower right (blue line). However, a water surface cannot appear so slanted; it always aligns itself with the Earth's surface. The principle that water always levels itself is utilized, for example, in a spirit level. Only from a greater height does the Earth's surface take on a curved, but never slanted alignment. Therefore, this line cannot be a "real" horizon line, nor can it represent a body of water due to the slanted appearance on the right side.

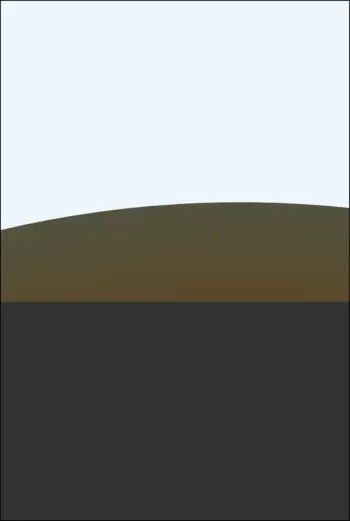

The Orange Horizon

A second painted horizon line is suggested by a complementary contrast that runs below the top third of the painting. The orange-brown earth tones sharply border along a circular line from a blue color field above it (green line). The unnaturally blue color field above can also be interpreted as a dark cloud wall, for instance, during a severe storm, due to its color and blurry forms. However, this line is too strongly curved for a real landscape (green line). For such a round-looking horizon, one would have to look at the Earth from a very high altitude.

Conclusion on the Different Horizons of the Mona Lisa

Regarding the perspective used, there initially appears to be an inconsistent overall impression. Leonardo was a master of perspective, so painterly incompetence can be ruled out. Perhaps the background landscape shows a picture within a picture, meaning a painted wall or tapestry. This would explain both the unfinished overall impression and the perspective errors. Especially the vanishing point of the columns at the edge of the painting is clearly faulty.

The situation is different if Leonardo wanted to depict the four perspectives (person, architecture, blue and orange horizon) as multiple superimposed views of a landscape, shown from progressively higher viewpoints.

- In this case, viewers would initially see the Mona Lisa sitting next to her, looking at her

- The architectural horizon line is high in the painting, indicating that the scene is viewed from a low standpoint, but still above the Mona Lisa's head, for instance, by a person not sitting next to her but standing (white line)

- The blue horizon line is lower, indicating that the scene is now viewed from a higher standpoint. The horizon line only slightly slopes downward on the right side (blue line)

- The orange horizon line is even lower, indicating that the scene is now viewed from an even higher standpoint. The horizon line is strongly curved (green line)

The order can also be reversed. In this case, viewers would first see the Mona Lisa from a great height and then descend to her in three stages until reaching eye level. The motif of great height, of ascending into the air, is a central theme in Leonardo's life. Around 1505, two years after starting work on the Mona Lisa, Leonardo conducted flight experiments with the flying machines he constructed at Swan Mountain near Florence. He developed screw propellers (helicopters), and he invented a functional parachute that glides vertically downward.

In contrast to the Mona Lisa, the predecessor painting does not depict supporting columns or similar elements. Therefore, the vanishing point of a central perspective cannot be determined here.

IV The Motif of Water

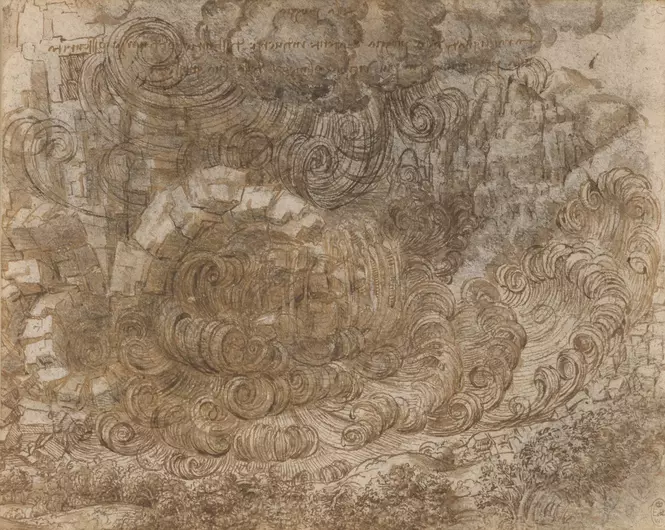

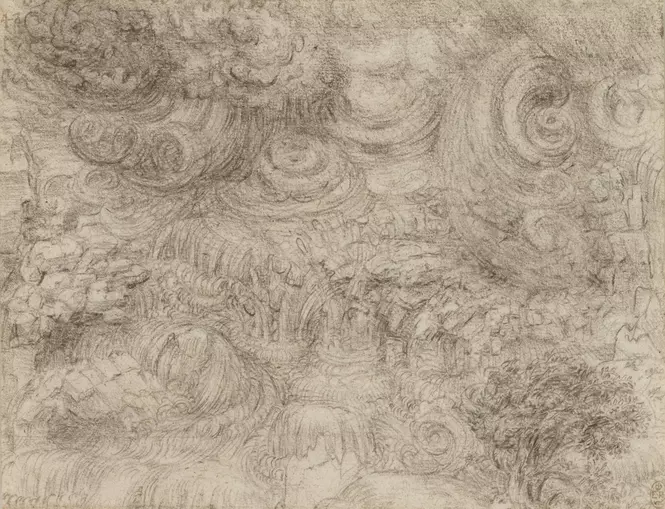

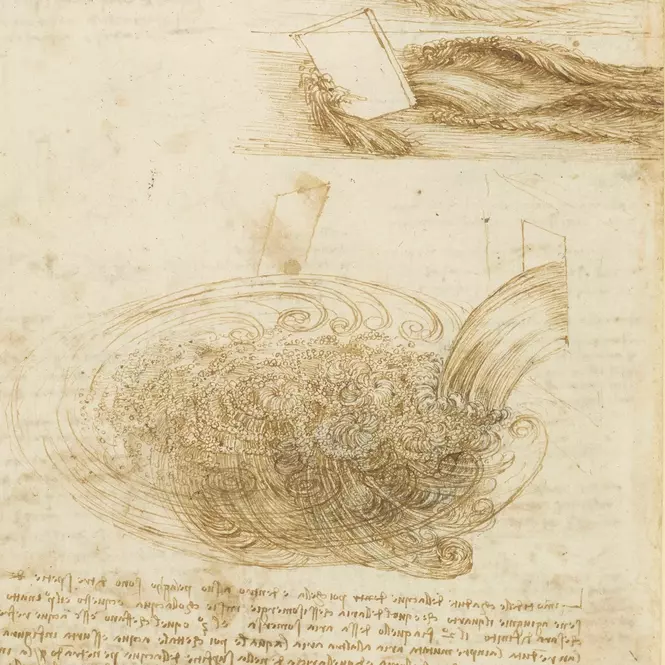

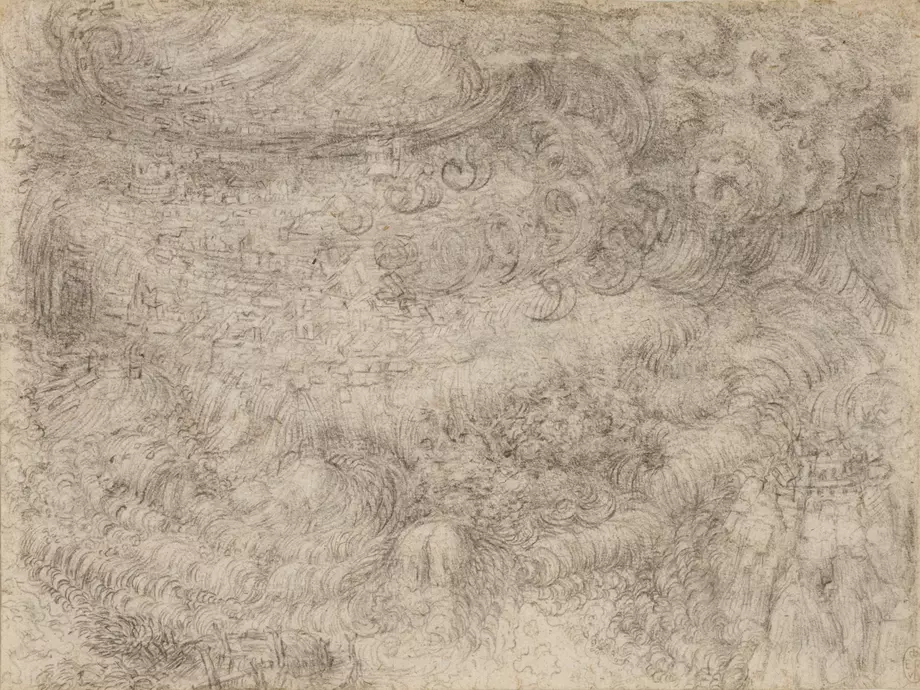

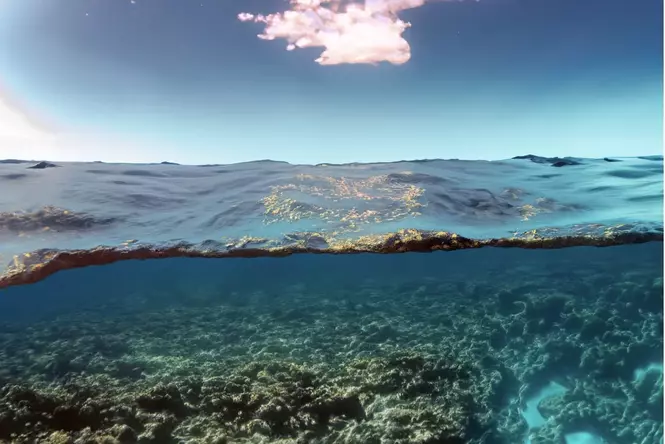

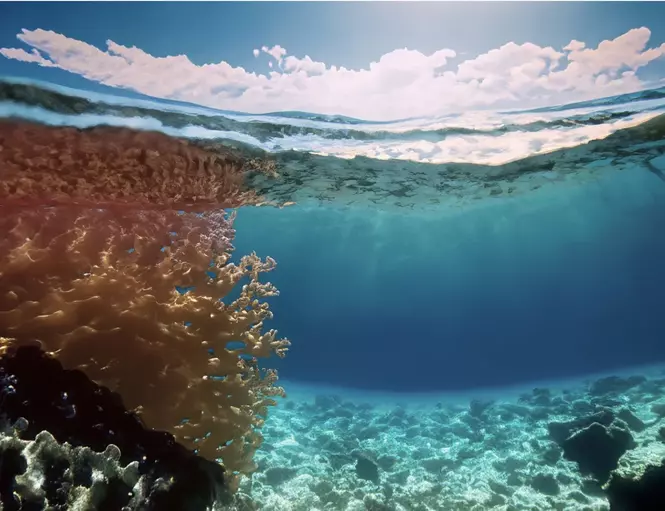

One of the leading motifs in Leonardo's work is water and the associated force of movement. Three years before starting work on the Mona Lisa, around 1500, Leonardo was in Venice. The Republic was at that time in conflict with the Ottomans, who posed a threat to Italy from the Balkans. Leonardo recommended the construction of a dam that, upon its destruction, would annihilate the Sultan's armies. Drawings of a devastating flood were likely created in this context.

Leonardo is regarded as the first scientist since antiquity to systematically study fluid dynamics, a branch of physics

The transparently painted ruching in the chest area of the dress is often associated by many authors with the appearance of falling water

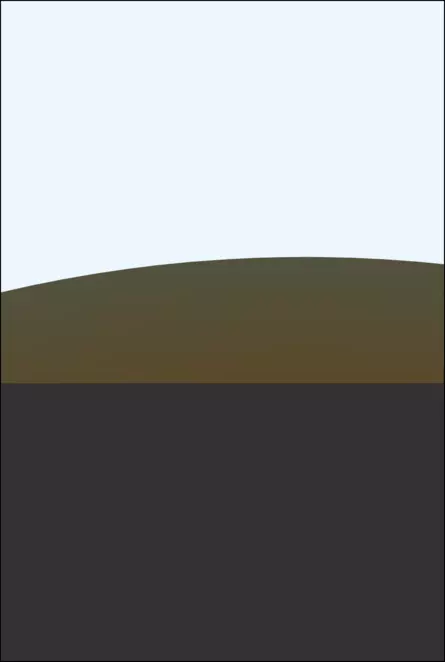

Right Background: Masses of Water

Formally, the painting, with a aspect ratio of 2:3, can be divided into six squares. The vertical division of the painting is emphasized by the perpendicular bisector, which passes through the left eye of the Mona Lisa. The landscape is situated in two quadrants on the left and right sides of the Mona Lisa. The landscape exhibits different characteristics on the left and right sides.

Let's first consider the right landscape in isolation. To do this, the left half of the image and the silhouette of the Mona Lisa are colored IV. In the less detailed landscape, two accents are highlighted. The first accent is a bridge, located just below the first third of the two squares. The bridge acts as the visual centerpiece of a calm and idyllic area with orange and light tones.

Above this, in complementary contrast to the lower orange, a massive blue area rises. It begins or ends at the level of the Golden Ratio of the two squares (orange horizontal). In the context of the landscape, it is supposed to represent mountains with a large lake on top. However, the rock wall appears too blue for mountains, and the water is not level. Even though the painting has undergone slight color changes over the centuries, it did not result in the mountains appearing bluer today than painted by Leonardo. A well-preserved copy created parallel to the Mona Lisa by Francesco Melzi also shows this unnatural color scheme for mountains. The harsh transition from orange to blue cannot be explained by the use of aerial perspective discovered by Leonardo (distant objects appear bluish), as the orange foreground should gradually transition into the blue background.

Therefore, the blue area cannot represent mountains. Instead, it seems to depict masses of water. It gives the impression of a gigantic surging tidal wave, as noted by Leonardo expert Martin Kemp. It appears to rush down into the valley, threatening to destroy everything in its path. To estimate its enormous size, a bridge was placed in front of it. The bridge is the only man-made structure in the background landscape.

It has been demonstrated that this work was created in parallel with the Mona Lisa, as various layers of paint show the same compositional changes. Like the original, the background here is strictly separated into orange and blue tones. Additionally, it becomes clear that Melzi copied without being able to capture the character of the original. Certainly, the vibrant colors in Melzi's work only approximate the appearance of Leonardo's Mona Lisa at that time

In a direct size comparison with the bridge, the flood wave appears gigantic

Characteristic of a tidal wave is a high, forward-curved, monochromatic water wall with a foam crown appearing as a horizontal white line. In front of it are much smaller, broken waves with a foamy structure

The tidal wave interpretation of the Mona Lisa by Martin Kemp

Martin Kemp was a professor of art history at the University of Oxford, with guest professorships at Harvard and Princeton, and is considered the world's most renowned Leonardo expert. He formulates the depiction of the flood in Leonardo's Mona Lisa as follows:

"The landscape of the Mona Lisa, situated on two levels - the higher water surface on the right side [of the painting] is above its natural position - is the quintessence of what Leonardo had learned when contemplating high and low places in Tuscany. The instability of one of the mountains to the left of the head [i.e., from her perspective, on the left], which has an extremely pronounced rock ledge and is deeply incised below, suggests that things will change radically at some unknown time in the future. A tremendous transformation is imminent, where the gently meandering rivers in the lowland under the Mona Lisa's balcony, with the neatly crafted bridge, will be surprised and reshaped by a force majeure against which any human engineer is powerless." (Kemp, Martin [2005]: Leonardo. Munich: Verlag C.H. Beck oHG, pp. 176 f.)

According to Kemp, Leonardo aimed to depict the immense power of the water rushing into the valley. Kemp presents these observations in the chapter 'Master of Water,' specifically in the context of Leonardo's attempts to harness the uncontrollable power of water.

Around 1500, Leonardo created a series of about 10 drawings of this kind, illustrating the destructive power of water. In this depiction, buildings of a city in the left upper background are barely recognizable. In the right foreground, there is a tall, solid rock on which a stately estate is situated. The estate would offer a similar view of the flood wave as seen from the balcony of the Mona Lisa

V Deluge

If Leonardo hints at such a massive tidal wave, he must have had in mind the most famous flood in human history—the biblical Deluge, in which the God of the Bible intended to eradicate all evil from the world. Before that, He had warned Noah to save himself, his family, and numerous animals on a self-built ark. Noah's story is told in the first book of the Bible, Genesis.

Silhouette, Mountain, and Light on the Horizon

Indeed, on the right half of the painting, there are references to the biblical flood story. Leonardo did not have to paint the Mona Lisa so that she stands out from the background with a dark color all around. He did so to emphasize her silhouette, just as he led the central axis of the painting through Mona Lisa's left eye, dividing it into a left and a right half.

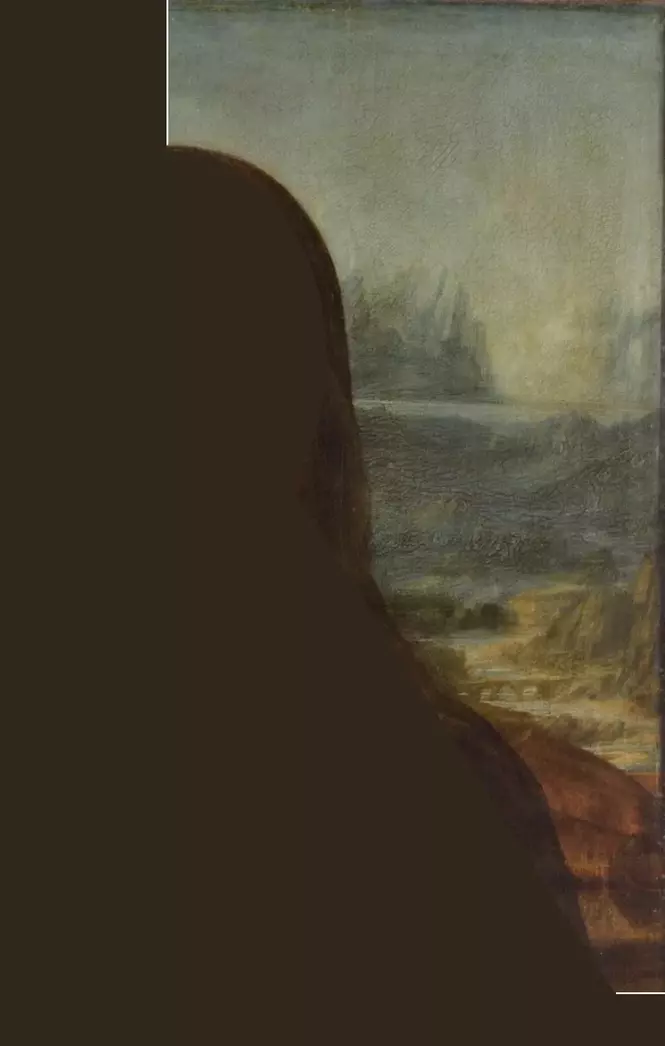

- The right silhouette of the Mona Lisa appears as a person viewed from behind in backlight, looking into the distance over a railing, the tidal wave still far away (IV, Mouseover). The back of Mona Lisa's head almost perfectly describes a quarter-circle only in the right half of the image (lower illustration). With this geometric peculiarity, Leonardo once again underscores the division of the background into a right and left half, directing the viewer's attention to the upper right quadrant of the painting I

- The high mountain from which Mona Lisa's balcony overlooks the landscape suggests Mount Ararat, where Noah's Ark landed after the flood (Gen 8:4).

- On the right half, not the left, a bright sunshine is visible on the horizon, shining over a body of water. The color mood recalls the end of the flood: "In the six hundredth year of Noah’s life, in the first month, on the first day of the month, the waters were dried from off the earth. And Noah removed the covering of the ark and looked, and behold, the face of the ground was dry." (Gen 8:13)

The dimensions of Noah's Ark

These intuitive and approximate impressions find justification in the concrete proportions in the lower part of the painting. The geometric relationships there correspond to the dimensions of Noah's Ark mentioned in the Bible:

"Make yourself an ark of cypress wood. Make rooms in it and coat it with pitch inside and out. This is how you are to build it: The ark is to be three hundred cubits long, fifty cubits wide, and thirty cubits high. Make a roof for it, leaving below the roof an opening one cubit high all around. Put a door in the side of the ark and make lower, middle, and upper decks." (Genesis 6:14-16)

Accordingly, the ark had the dimensions of the golden ratio:

- It was 300 cubits long, 50 cubits wide, and 30 cubits high.

- The ratio of the side lengths was thus (divided by 10) 30:5:3.

- The ratio of width to height was 3:5 (0.6), pointing to the golden ratio, as 3 and 5 are Fibonacci numbers.

- The roof was to be raised by an additional cubit, making the highest point of the ark 30+1 cubits high.

- The ratio of 31:50 (height of the roof and width of the ark) was therefore 0.62, close to the golden ratio, which is 0.618.

- An ark with a width of 1 thus had a raised roof with a height between 0.6 and 0.62.

Additionally, the entrance to the ark was to be on the side.

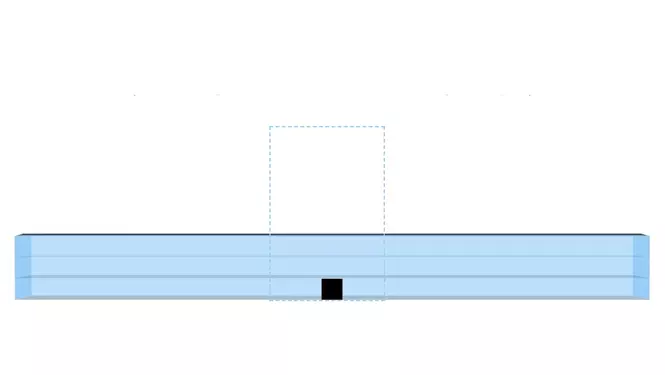

The dimensions of the wall

Leonardo uses the dimensions of Noah's Ark mentioned in the Bible for the geometric relationships in the lower third of the painting V.

- If the height of the wall is extended to the lower edge of the railing (upper green line) by 1/30, it leads to the height of the column bases, i.e., the golden ratio of the image height (orange line). The roof of Noah's Ark was to be raised by 1/30. The height of the Ark itself is in the golden ratio to its width (30:50 or 31:50)

- When the height of the wall is divided into thirds, it runs along the upper edge of the chair back (mouseover, green lines). It takes little imagination to recognize the entrance of the Ark in the gap between the first two columns of Mona Lisa's chair, even if it is formed by a semicircular chair back and is therefore not entirely horizontal. Overall, however, the impression of an entrance area is confirmed, thus forming the first floor of Noah's Ark. The entrance is exactly in the middle of the painting. The Ark would thus be depicted from the side

The geometric symbolism used clearly refers to the dimensions of Noah's Ark, confirming the overly blue-painted mountains in the right background as the masses of water of a biblical flood that destroys all life.

Two long stones were placed on a wall as a parapet. The lower parapet stone was either decoratively carved or is naturally layered as rock. It casts a slight shadow on the underlying wall

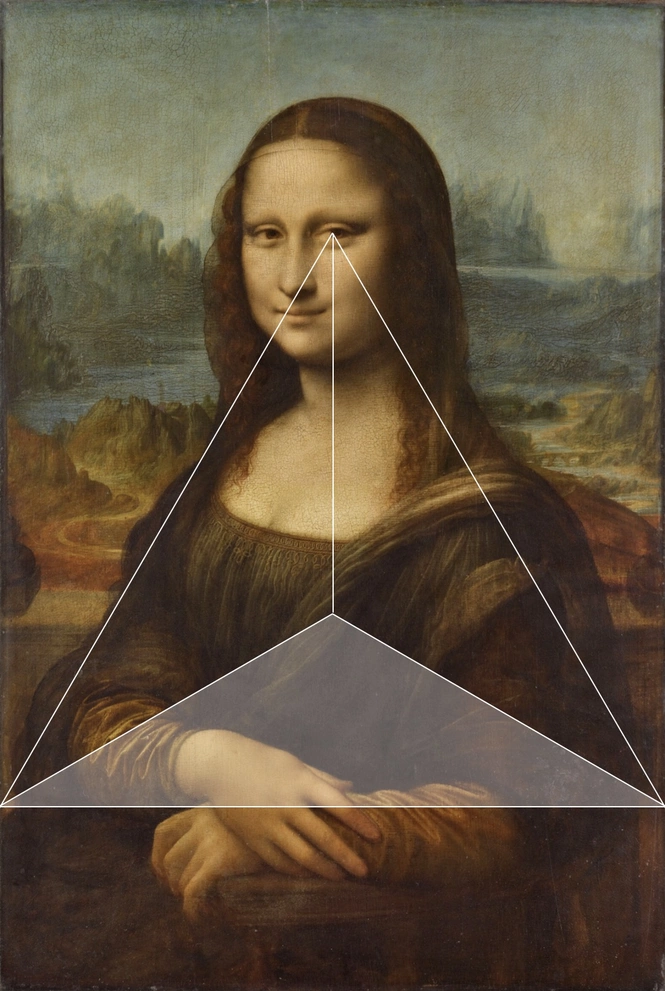

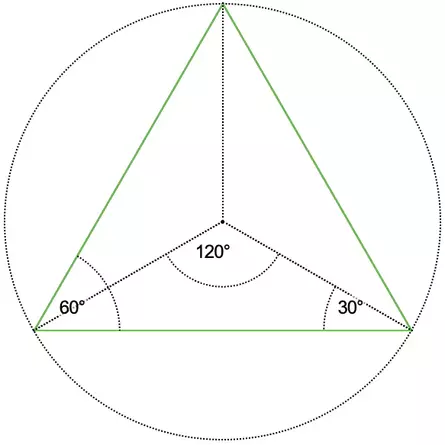

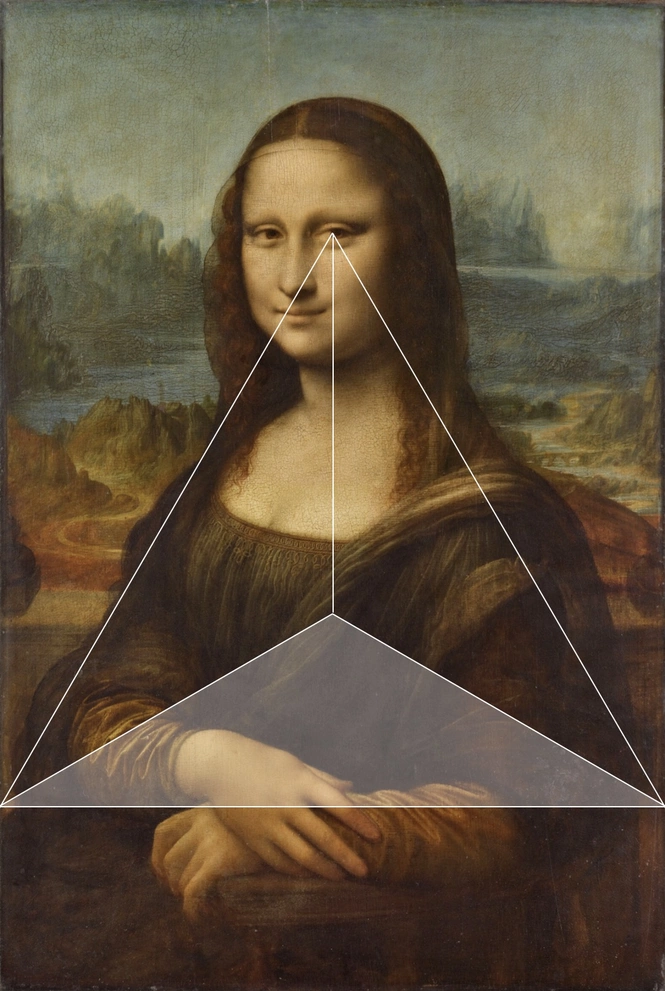

VI The Equilateral Triangle

Something remarkable emerges when the height of the wall is not divided into thirds, but instead halved. The idea for this comes from a subtly indicated horizontal line that can be seen at the left and right edges of the painting. The copy created by Francesco Melzi, which is identical in the fundamental composition and was created at the same time, also shows a change in color at the midpoint of the wall.

In the contemporary copy by Melzi, the division at the halfway point of the visible part of the wall is also evident (gray and orange)

Further Geometric Relationships of the Background Wall

- At half the height of the wall, an isosceles triangle with interior angles of 30°, 30°, and 120° can be constructed (white-transparent area). Such a triangle is formed by the angle bisectors in an equilateral triangle. The apex of the triangle touches the golden ratio of the image height (orange horizontal line)

- From the left eye of the Mona Lisa, which is already emphasized by the perpendicular bisector, two lines can be drawn to the base of the isosceles triangle. This creates an equilateral triangle, meaning the interior angles are 60° (white diagonals)

- The distance from the eye to the apex of the isosceles triangle corresponds to the distance from the column bases to the lower edge of the image, i.e., the golden ratio of the image height (white central vertical line)

These relationships may not be exact in terms of the fundamental aspect ratio of 2:3, but the points are so close together visually that chance is conceivable, yet a geometric-constructive intention is more likely. It is unlikely that the image composition was randomly chosen so that the marking of the triangle base appears exactly at the midpoint of the height of a wall in the background. Leonardo must have consciously divided the wall at that point.

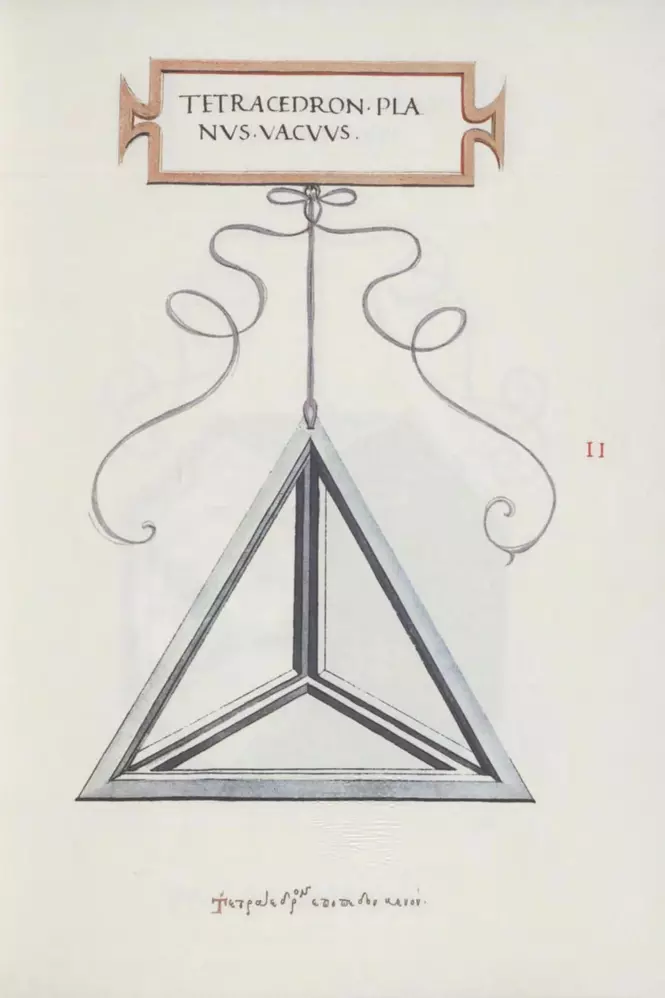

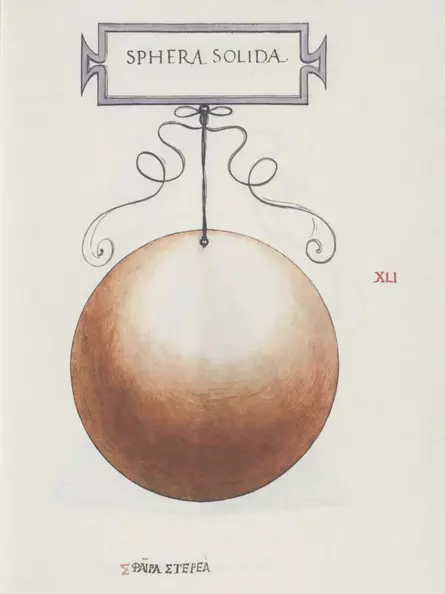

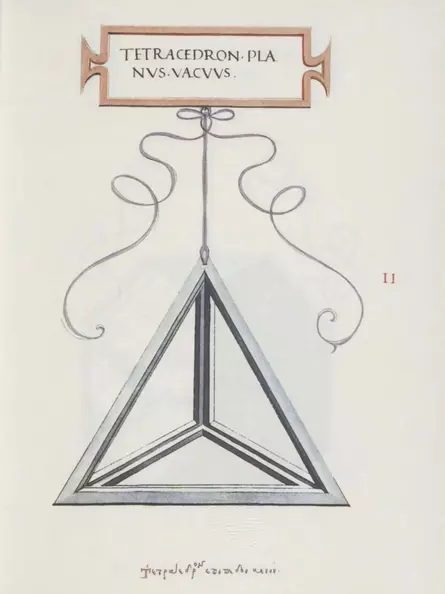

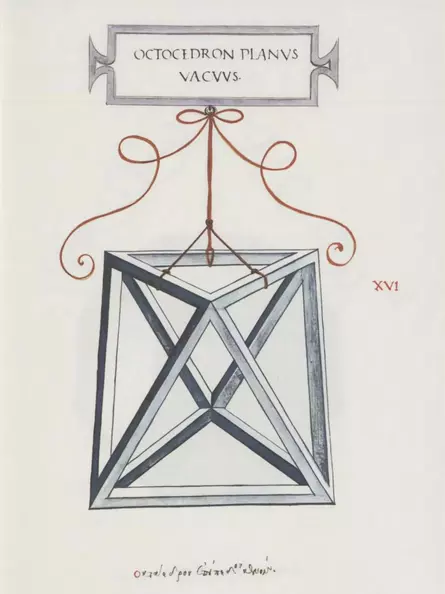

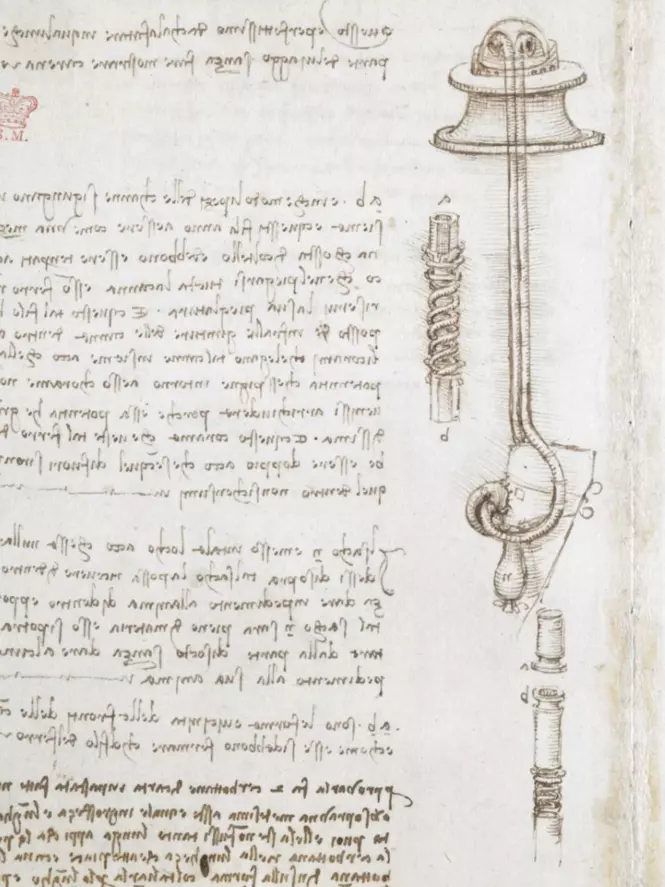

Collaboration with Luca Pacioli

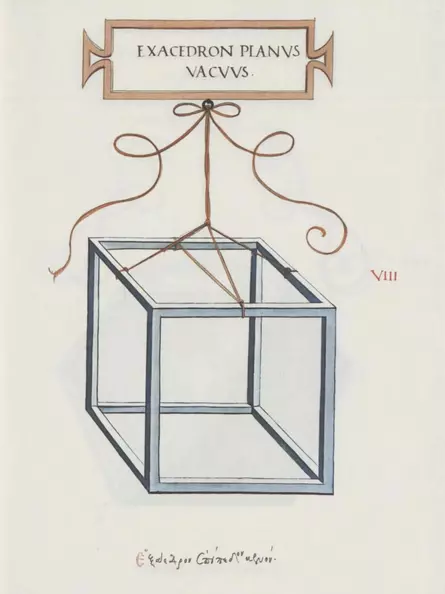

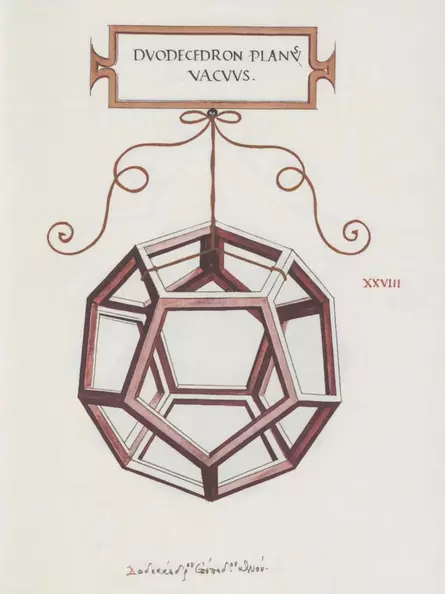

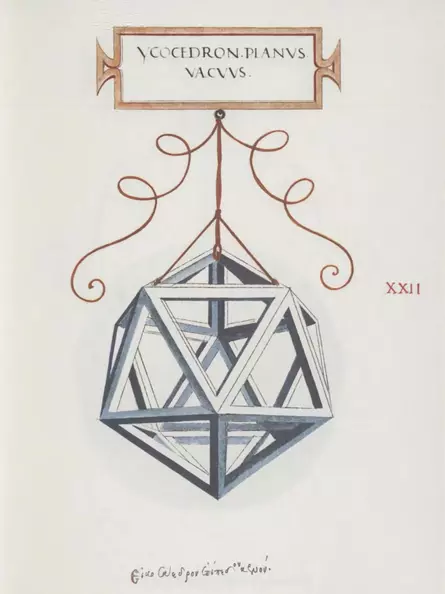

Leonardo and the significant mathematician Luca Pacioli were in close contact since at least 1498 when Pacioli began working for the Milanese court. In this period, Pacioli completed his book "Divina proportione" (around 1498), which deals with the golden ratio in nature and its application in art and architecture. Leonardo created numerous illustrations for this work, including drawings of the Platonic solids, such as the tetrahedron. These geometric shapes were depicted in a novel skeletal structure that highlighted the spatial relationships of the bodies. The intensive exploration of geometric studies continued with Leonardo from 1501, as evident from his notebooks and contemporary letters. Leonardo then commenced work on the portrait of the Mona Lisa in 1503. Due to financial constraints, Pacioli's book was only published in 1509.

A page from the manuscript of Pacioli's book "Divina Proportione" ('Divine Proportion'). The 60 illustrations depict geometric solids in this entirely novel skeletal structure, greatly enhancing their clarity

At the time of the painting, Leonardo was around 43 years old.

Pacioli, depicted here in monastic robes, was a Franciscan. The Franciscans were a medieval monastic order founded by St. Francis of Assisi (1181-1226).

Pacioli has drawn an equilateral triangle on a panel while gazing at a glass cuboctahedron.

The mathematician Pacioli surely approached the Bible with a focus on numerical aspects as well

Left background landscape

Up to this point, only the right background landscape has been examined. It has been demonstrated that this landscape is threatened by a tidal wave, referencing the biblical flood narrative. The geometric construction in the lower third of the painting corresponds to this visual representation and incorporates the dimensions specified for Noah's Ark in the Bible. Building upon this, the left eye of the Mona Lisa, emphasized by an equilateral triangle, points to the center of the painting.

With the observation that the painting exhibits some geometric peculiarities, let's now take a closer look at the left side of the image.

VII Anamorphic Image – The Family

Leonardo's paintings always reveal, in addition to the obvious representation, further hidden images that may be more or less challenging to discover. The techniques used for these depictions are collectively referred to as anamorphic images. Throughout his entire body of work, Leonardo demonstrates a playful engagement with the resemblance of images, not limited to his paintings alone.

A forward-facing mouth has been positioned in a way that forms the eyes of a face

The legs of the rear Anna could also be the legs of a standing Mary

The head of Doubting Thomas (on the left, called the Twin) appears to be emerging from the body of the other.

The left half of the face looks directly at viewers

The Maternal

The Mona Lisa is often described with maternal qualities: gentle, warm-hearted, and caring. Few people are aware that Leonardo emphasizes this indistinct feeling through hidden images, among other things.

The Paternal

On the right side of the painting, the outline of an unnaturally falling, almost transparent veil can be discerned VII. In conjunction with her reddish-brown, wavy falling locks, the facial shape of a bearded, older man can be recognized, gazing reverently towards the lower left in the direction of the left pillar base (Mouseover). The head is smaller than that of the Mona Lisa, so it must be positioned behind her.

The Child

The hair of the Mona Lisa appears to fall down to her elbow over her right shoulder. Upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that the hair-like structure on her right shoulder is the heavily compressed transparent veil covering her head and shoulders. Nevertheless, the area of the right shoulder appears like a part of her hairstyle. There is an impression that the Mona Lisa is embraced by a younger child coming from the left edge of the painting, burying its face into her right side. Particularly impressive is the depiction of the right arm of the Mona Lisa, which now becomes the right arm of the child.

Leonardo's painting started two years earlier but still unfinished in 1503, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, also plays with a distorted variation of the theme of father, mother, and child. Leonardo probably continued working on it around the same time as the Mona Lisa from 1508 onwards when he returned to Milan after eight tumultuous years.

The Platonic Motif

Leonardo was revered by contemporary artists as an equivalent of Plato. Plato was a significant ancient Greek philosopher, a student of Socrates, and a teacher of Aristotle. He founded a school for higher education in Athens called the "Akademeia," located near the sanctuary of Akademos, from which the modern term "academy" is derived. Legend has it that there was an inscription above the entrance to the Academy: "No one should enter without knowledge of geometry". Plato sought to create a holistic synthesis of natural sciences, metaphysical ideas, ethical principles, and political theories.

The book "Timaeus" (Italian "Timeo")

One of Plato's most famous works is the book "Timaeus." It contains two themes whose connection is not immediately apparent. Firstly, it introduces the legendary city of Atlantis and vividly describes how it sank into the sea after a tremendous flood. Secondly, it explains the so-called Platonic solids, named after Plato. The connection between flood and geometry in "Timaeus" establishes a link with Leonardo's Mona Lisa.

Raphael portrays Leonardo as Plato with Timaeus

After giving the Mona Lisa its current appearance around 1508, Leonardo was depicted by the younger Raphael as Plato in "The School of Athens" (1510-1511). In the painting, Plato is holding the book "Timaeus." Raphael had seen the original version of the Mona Lisa in Leonardo's workshop in Florence a few years earlier and imitated it in three paintings.

The painting depicts the idealized construction site of St. Peter's Basilica. Additionally, four contemporary artists are portrayed as ancient figures who were involved in or will be involved in the construction of St. Peter's Basilica: Leonardo (the visionary), Bramante (the initial architect), Raphael (the second architect), and Michelangelo (the fourth architect)

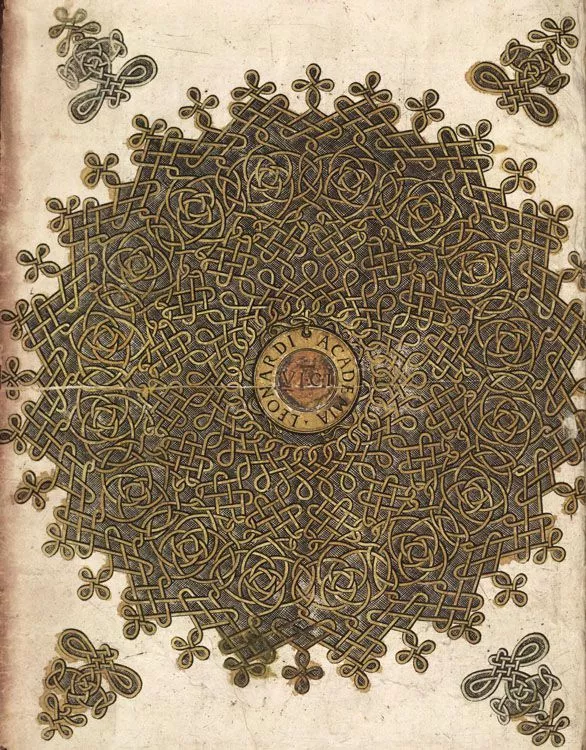

Leonardo's Academy